Page of

Page/

- Reference

- Intro

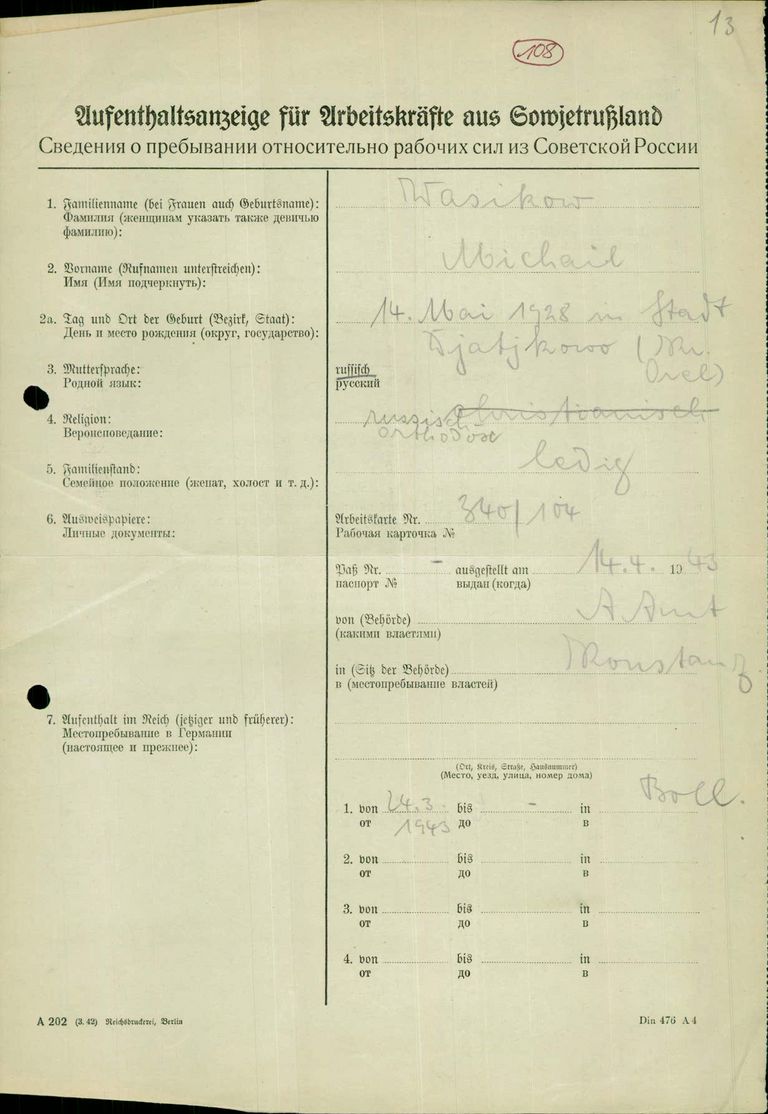

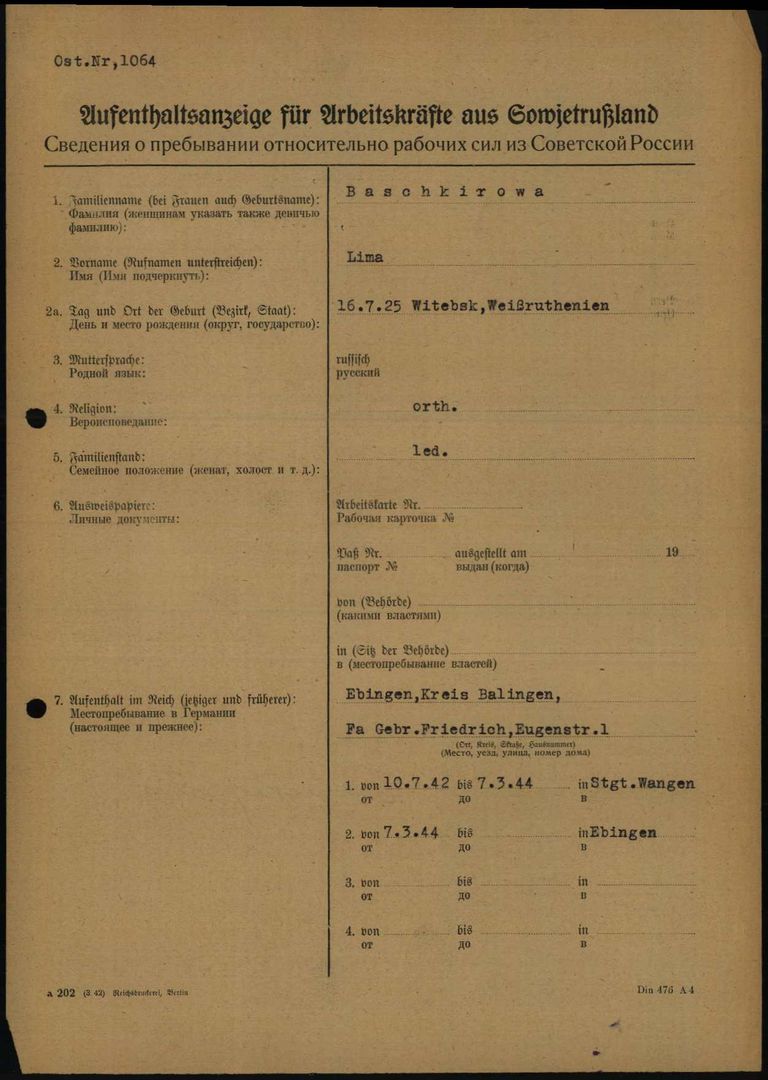

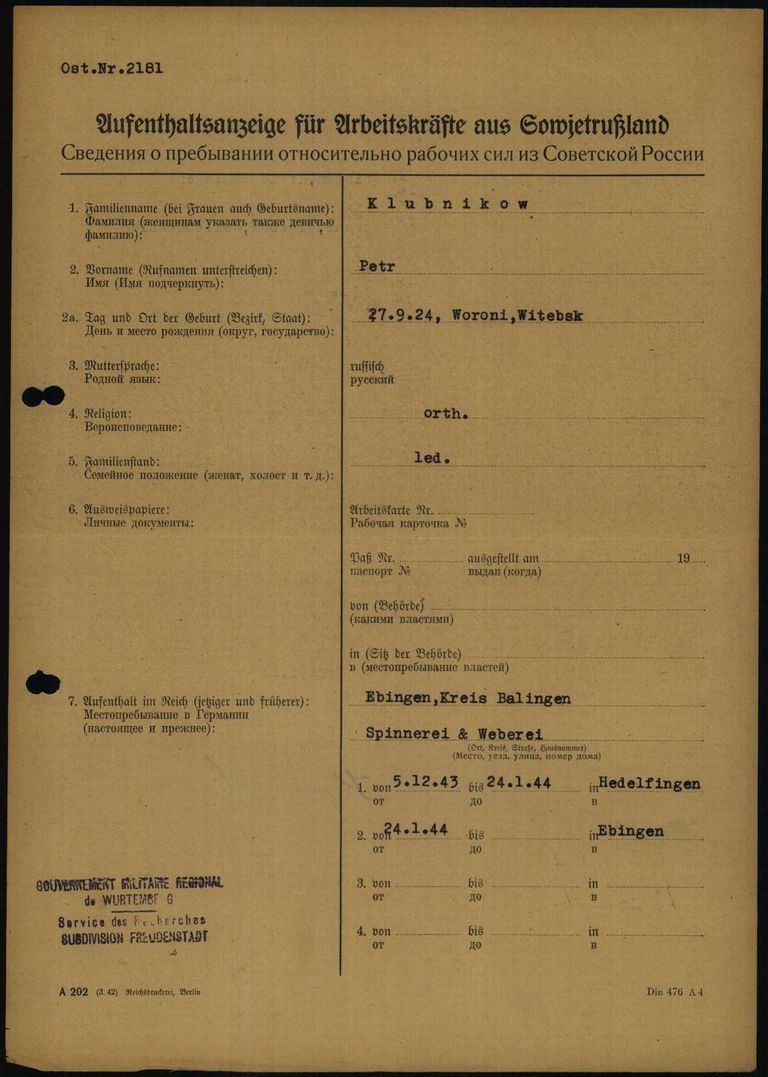

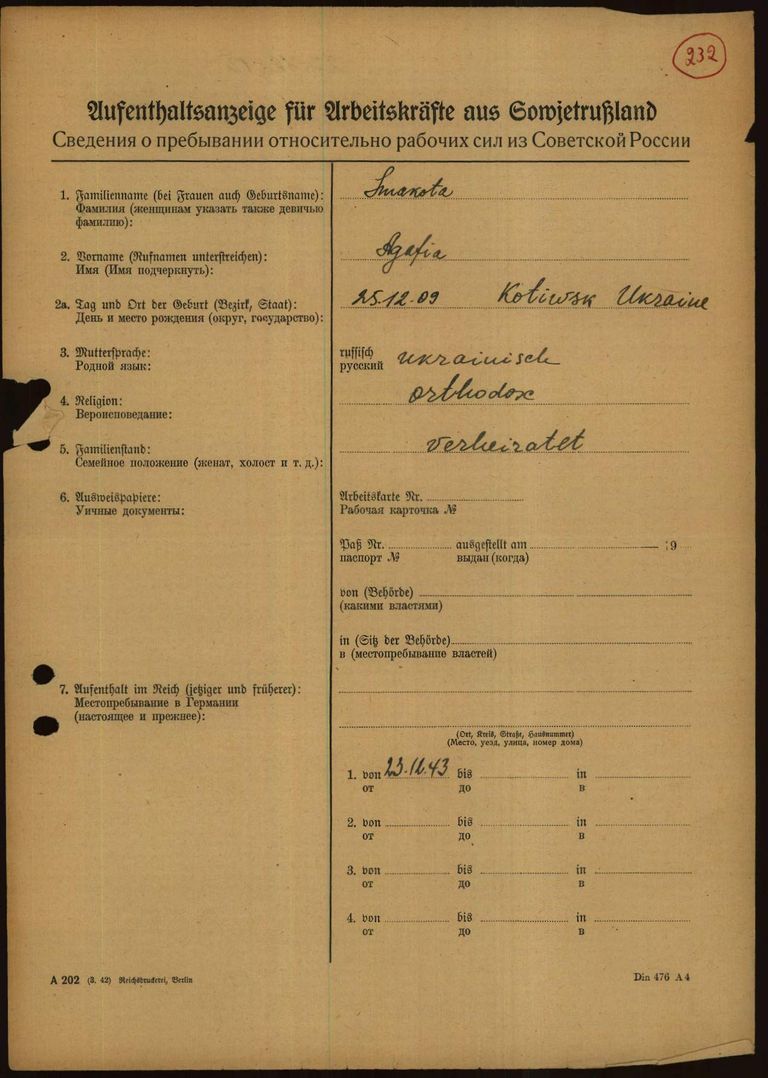

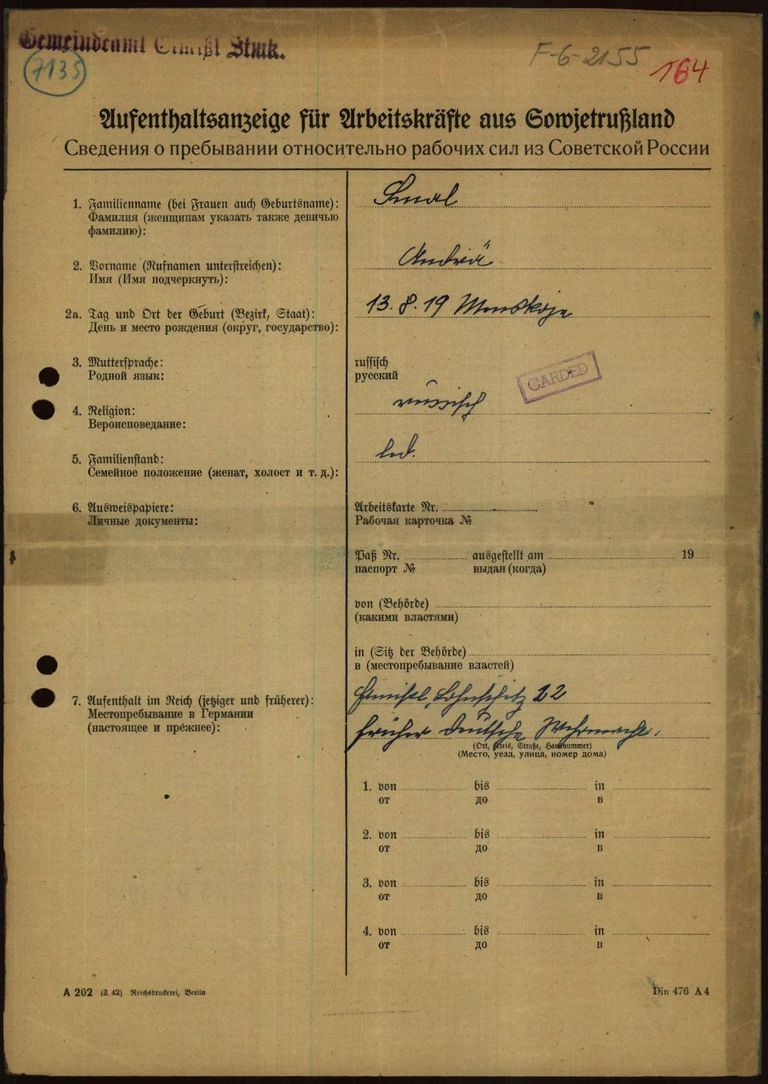

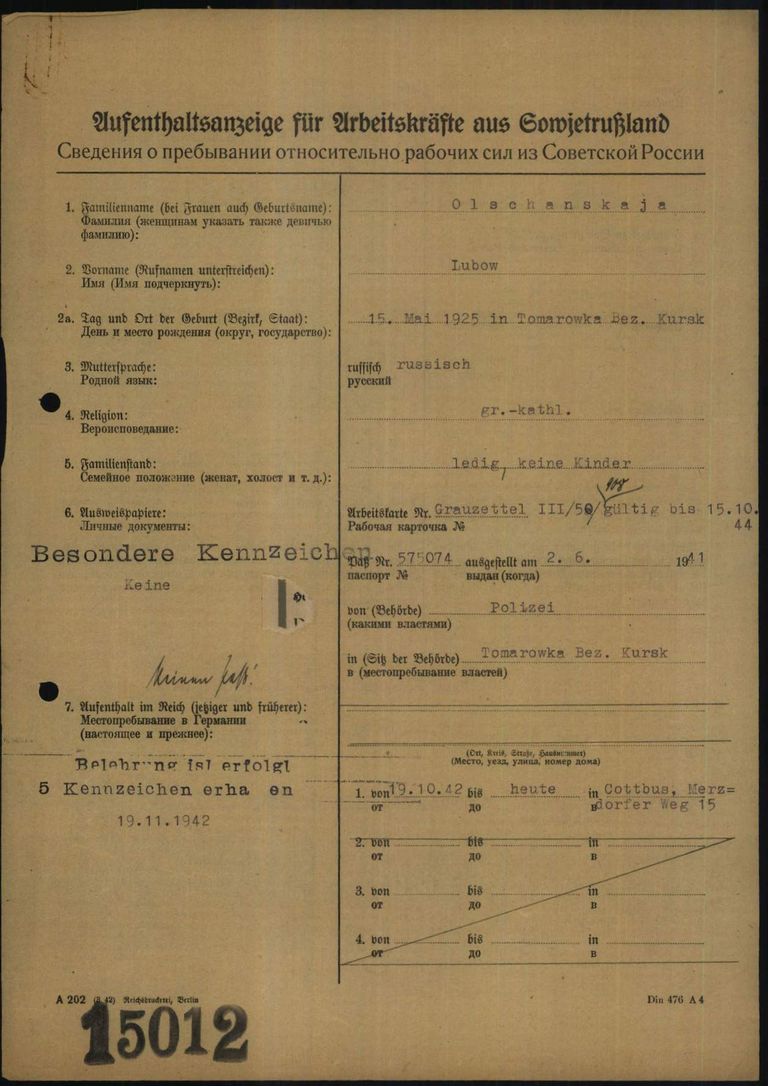

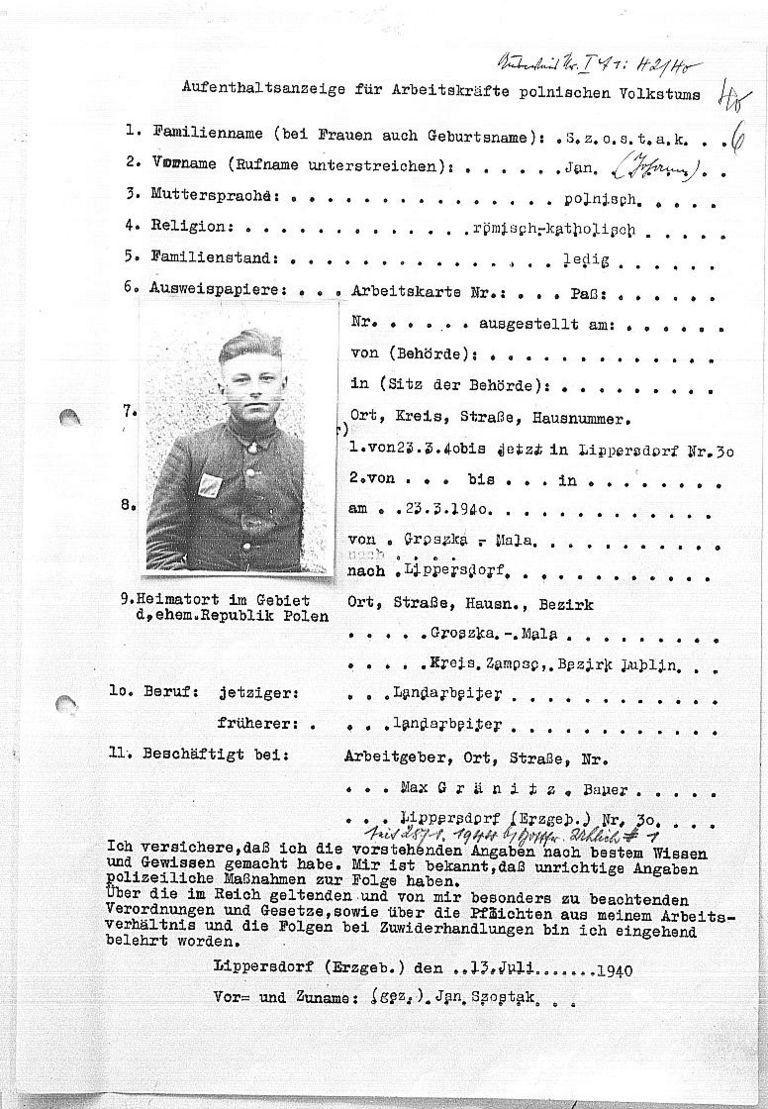

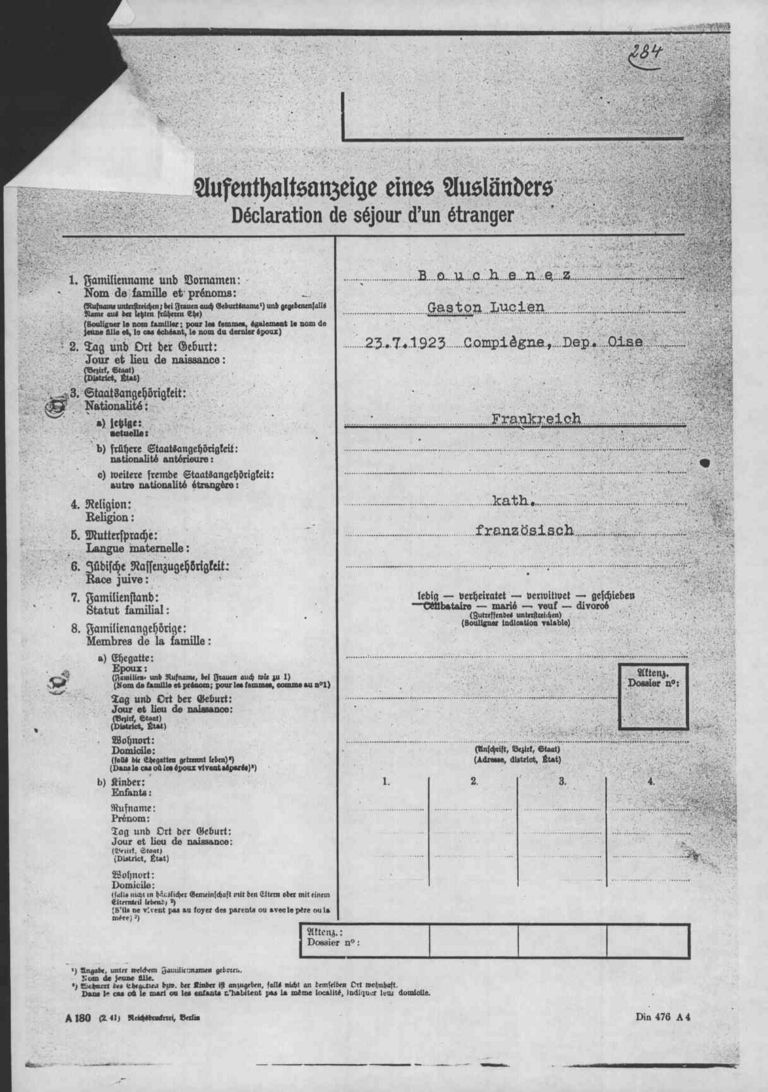

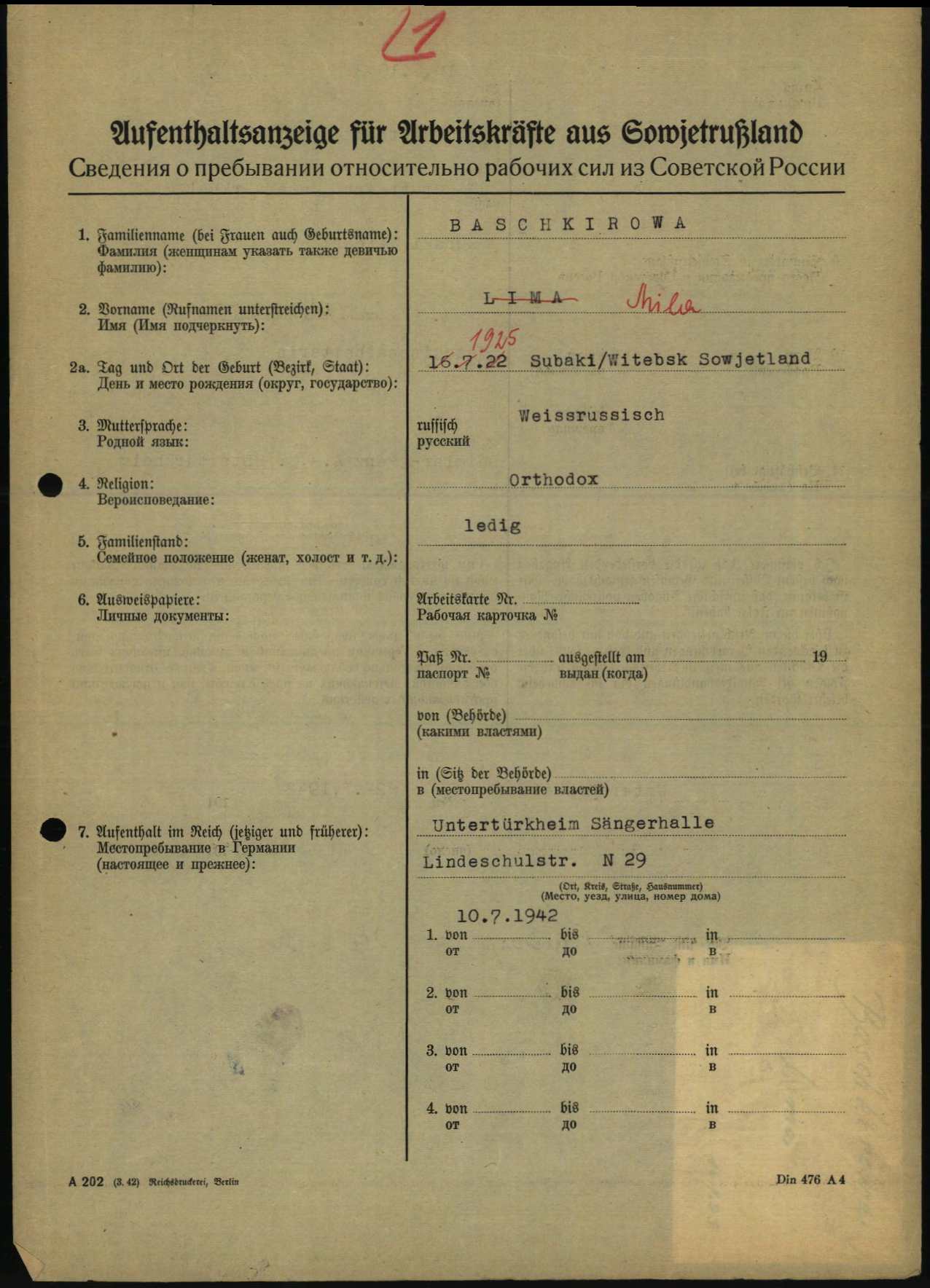

The Ausländerpolizei (foreigner police) maintained Ausländerakten (foreigner files) on all civilian laborers within their jurisdiction. A key document in these files was the bilingual Notification of Residence for foreigners. This document contains the name and native country of civilian laborers, as well as information related to their places of work. Special forms were used for forced laborers from Poland and the occupied areas in the Soviet Union, which were known as “Notifications of Residence for Laborers of Polish Nationality” and “Notifications of Residence for Laborers from Soviet Russia”.

The Ausländerpolizei (foreigner police) maintained Ausländerakten (foreigner files) on all civilian laborers within their jurisdiction. A key document in these files was the bilingual Notification of Residence for foreigners. This document contains the name and native country of civilian laborers, as well as information related to their places of work. Special forms were used for forced laborers from Poland and the occupied areas in the Soviet Union, which were known as “Notifications of Residence for Laborers of Polish Nationality” and “Notifications of Residence for Laborers from Soviet Russia”.

Questions and answers

-

Where was the document used and who created it?

All civilan forced laborers were initially housed in transit camps upon their arrival in the German Reich. These camps were initially run by Landesarbeitsämter (regional employment offices), and, as of 1943, by the Gauarbeitsämter (Gau employment offices). Following a medical examination, the forced laborers were registered at the employment offices and assigned to a workplace.

Every forced laborer then had to report to the police department at their respective place of work within 24 hours. The police officers there, who were generally the local police officers, created a Notification of Residence for every person and sent this document on to the municipal foreigner police. Each district had its own foreigner police administration, also known as the Foreigners’ Registration Office, which was part of the respective municipal police headquarters or the district administration as of 1940.

In order to register the arriving forced laborers more quickly, employees of the responsible police stations came to the transit camps when large-scale transports from the occupied eastern territories arrived. As of February 1944, dedicated branch police stations were even established in the transit camps by the responsible district police authorities. Their job was to photograph the forced laborers, issue Notifications of Residence and provide the workers with valid identification documents and residency permits. “A file was created containing who you are, where you come from, your name, date of birth, when you were first registered and your religion. […] I was registered and was immediately issued a number.” (Vikor Shabski, quoted in: Memorial Moscow (ed.): Für immer gezeichnet, p. 135).

- When was the document used?

It is currently unclear when the police authorities began issuing Notifications of Residence for foreign laborers. As the fundamental procedures governing the activities of the foreigner police had been issued as a regulation valid for the entire German Reich in 1938, it is safe to assume that the first Polish forced laborers were registered shortly after the war broke out. However, it is not yet known whether the special pre-printed form later used for the “Notification of Residence for Laborers of Polish Nationality” was used at that time.

Along with the Polish forced laborers, the Soviet forced laborers used in the German Reich were documented with their own “Notification of Residence for Laborers from Soviet Russia” form as of the end of 1941, and on a mass scale from 1942. This form refers to the special status of both groups, for whom racist special laws applied during their forced stay in the German Reich. The discrimination included the mandatory wearing of visible “P” and “OST” (for East) badges.

However, in order to save paper and working hours, no additional Notifications of Residence were issued as of 1943 for forced laborers from Poland and the occupied territories in the Soviet Union who had already been issued with labor cards and index cards of the foreigner police in the transit camps.

- What was the document used for?

The police officers in the Foreigner Police used the information from the Notifications of Residence to issue labor cards up to the fall of 1943. In the case of forced laborers from Poland or the occupied territories in the Soviet Union, two additional index cards of the foreigner police were filled out based on the Notifications of Residence. The photographs taken during the registration are therefore frequently glued to these index cards and labor cards. The forms were generally filled out with a typewriter; however, the Arolsen Archives also contain numerous Notifications of Residence filled out by hand using a pencil.

There were various preprinted forms for registering the forced laborers depending on the country of origin and native language. The Notifications of Residence were generally bilingual – in German and in the native language of the forced laborer. However, there are also pre-printed and typed forms which are only in German.

But the Notifications of Residence for Polish and Soviet forced laborers were not only used for issuing other documents, but also served a different purpose: The forced laborers had to confirm with their signature that they had been verbally informed about the valid laws and regulations applicable to them. The Reich’s government had already created a discriminatory special law, known as the Polenerlasse (“Polish decrees”), for forced laborers from Poland in March 1940. These decrees included the obligation to wear a “P” badge on their clothing. Two years later, in February 1942, Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer-SS and head of the German police, issued the Ostarbeitererlasse (“Eastern decrees”). Forced laborers from the occupied Soviet Union, who were known as Ostarbeiter (“Eastern workers”), also had to wear the “OST” badge visibly on their clothing from then on. Sexual relations with Germans were punished with the death penalty, and any (even minor) offenses could result in being transferred to Arbeitserziehungslager (AEL) (labor reeducation camps) or concentration camps, where thousands of forced laborers died during World War II.

- How common is the document?

During their registration, employees of the local police authorities issued Notifications of Residence for all civilian forced laborers, until this practice was terminated in September 1943, at least as far as Polish and Soviet forced laborers were concerned. This means that there must have been at least one Notification of Residence for each of the millions of civilian laborers. Additionally, a new Notification of Residence had to be issued each time the employment office assigned the laborers to a different workplace located in a different town.

The total number of Notifications of Residence issued for foreigners in the German Reich and how many of them ended up at Arolsen after the war (either as originals or copies) is not known. The employees of the International Tracing Service (ITS), the predecessor of the Arolsen Archives, merged the forms with many other documents in alphabetical order in what was known as the War Time Card File. This encompasses approximately 4.2 million documents.

- What should be considered when working with the document?

The police employees were instructed to take great care that the names and countries of origin were properly recorded. Nonetheless, some documents contain spelling mistakes or phonetically rendered spellings of the places of birth and last domiciles of the forced laborers. In addition, the information on the whereabouts of the civilian forced laborers was no longer updated or only recorded in rudimentary fashion during the last months of the war in particular, known as the final phase.

The Notifications of Residence generally only contain an entry made at the beginning of the civilian laborer’s employment, but not when it ended. This was only noted on the forms when the person was sent back to their native country before the end of the war, for example due to pregnancy or inability to work. There was no formal de-registration of the forced laborers with the local German police authorities following liberation by the Allied Forces. Either they returned directly to their home countries or they were registered as Displaced Persons (DPs). The registration documents issued by the German authorities for forced laborers during the war were no longer updated; rather, they were replaced by documents issued by the Allies, such as DP 2 cards.

If you have any additional information regarding this document, we would greatly appreciate hearing from you at eguide@arolsen-archives.org. The document descriptions in the e-Guide are updated on a regular basis – and this works best when everyone pools their knowledge.

Help for documents

About the scan of this document <br> Markings on scan <br> Questions and answers about the document <br> More sample cards <br> Variants of the document