Page of

Page/

- Reference

- Intro

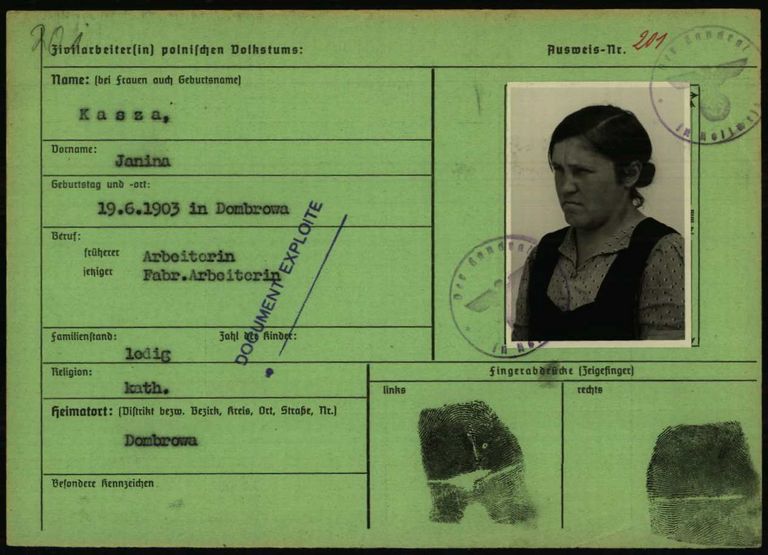

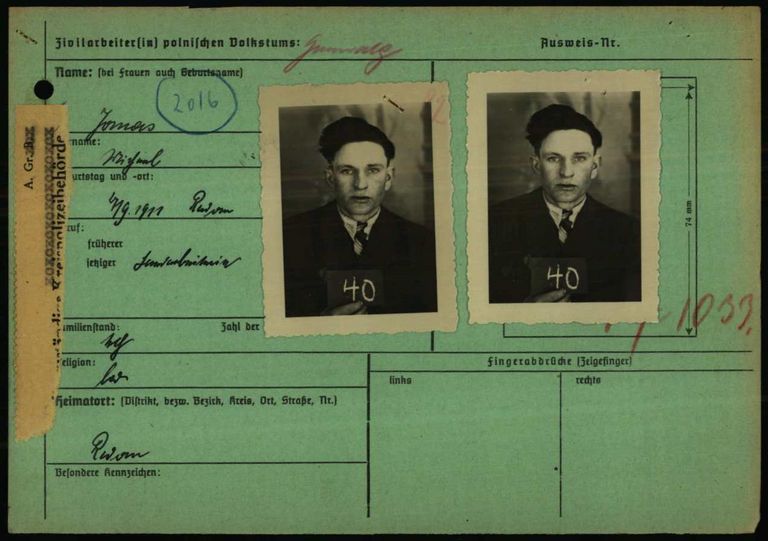

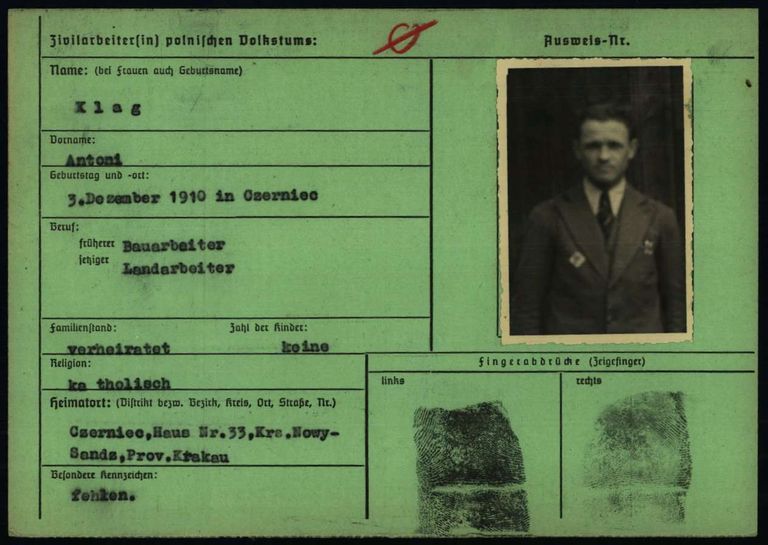

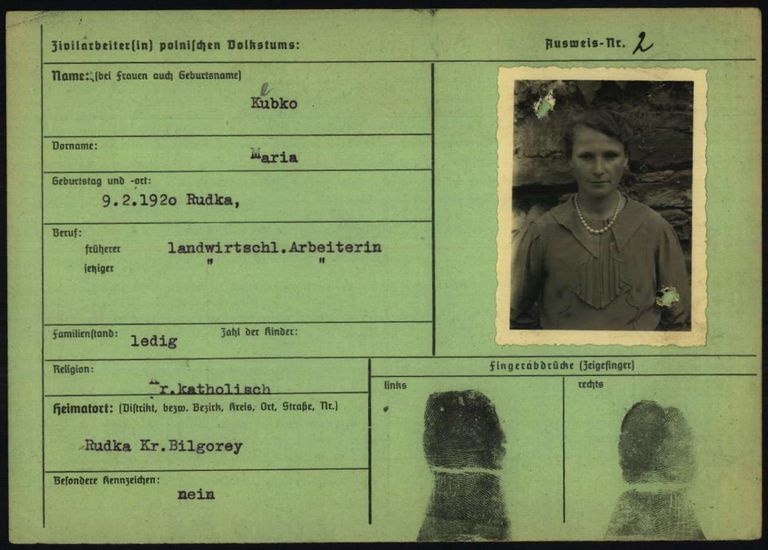

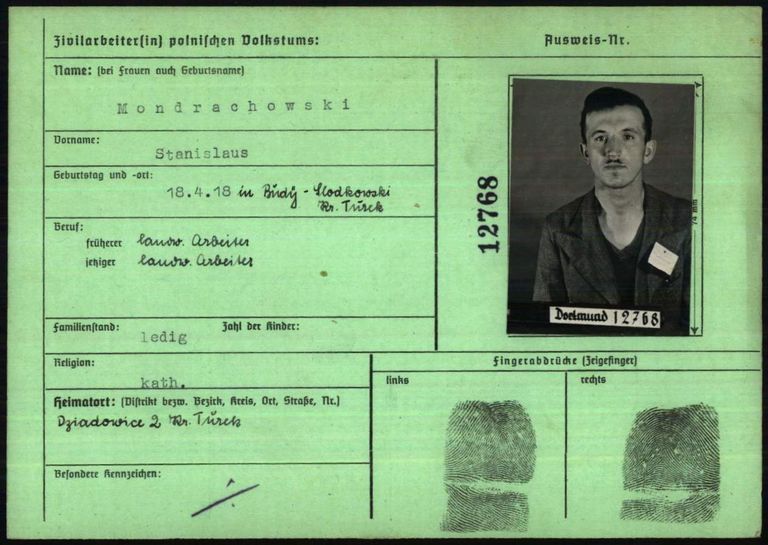

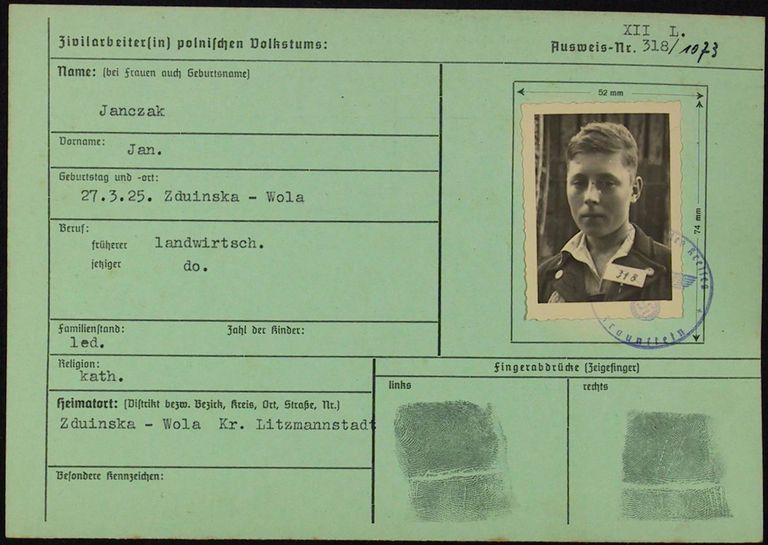

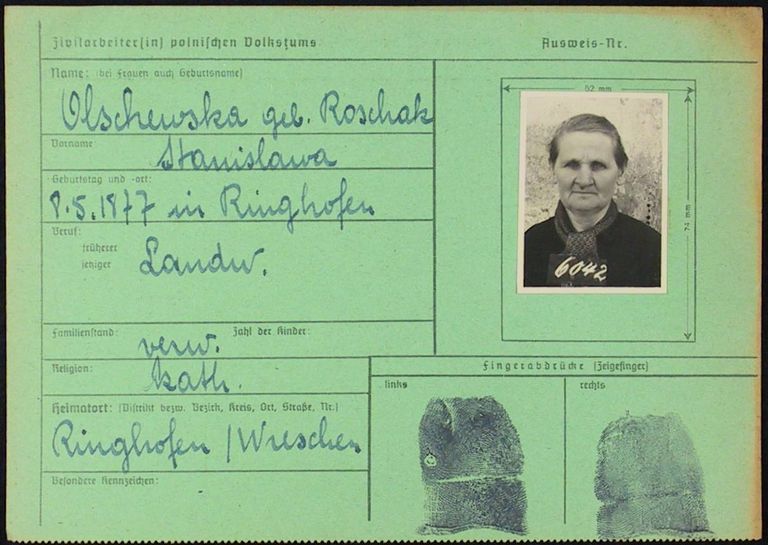

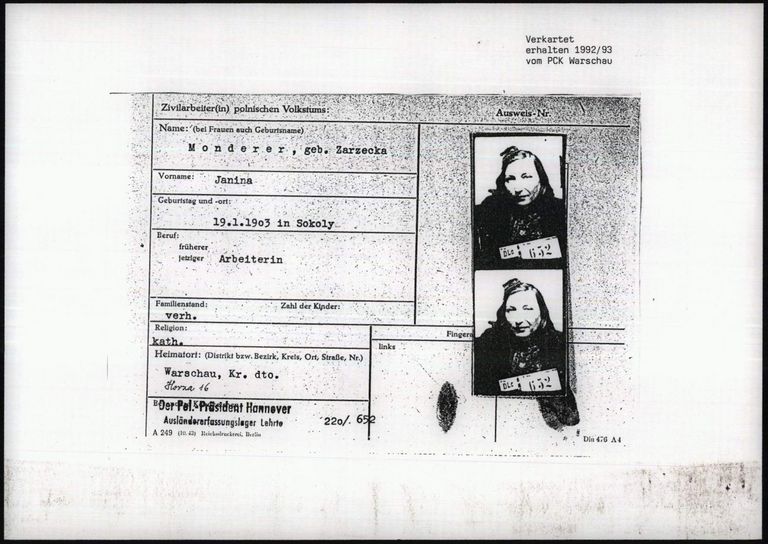

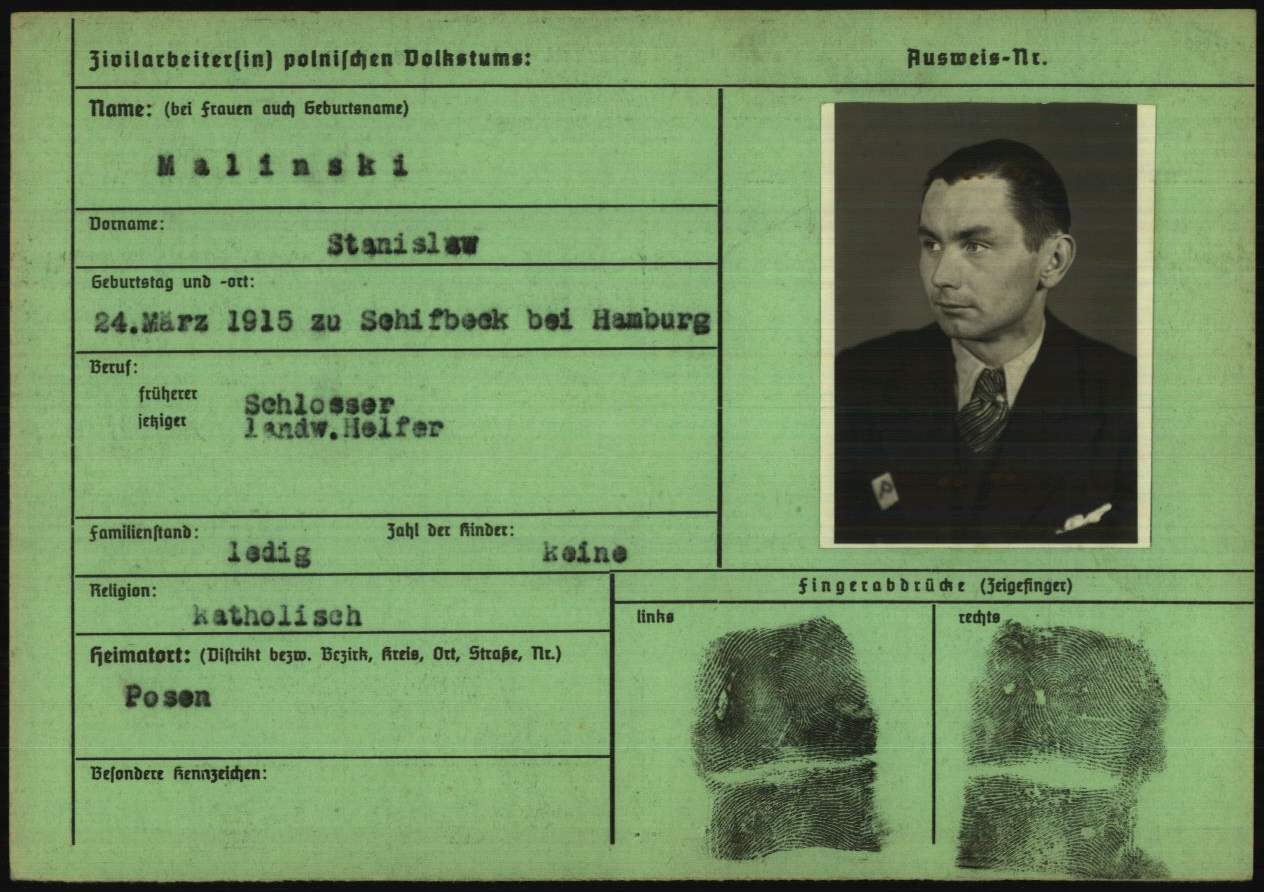

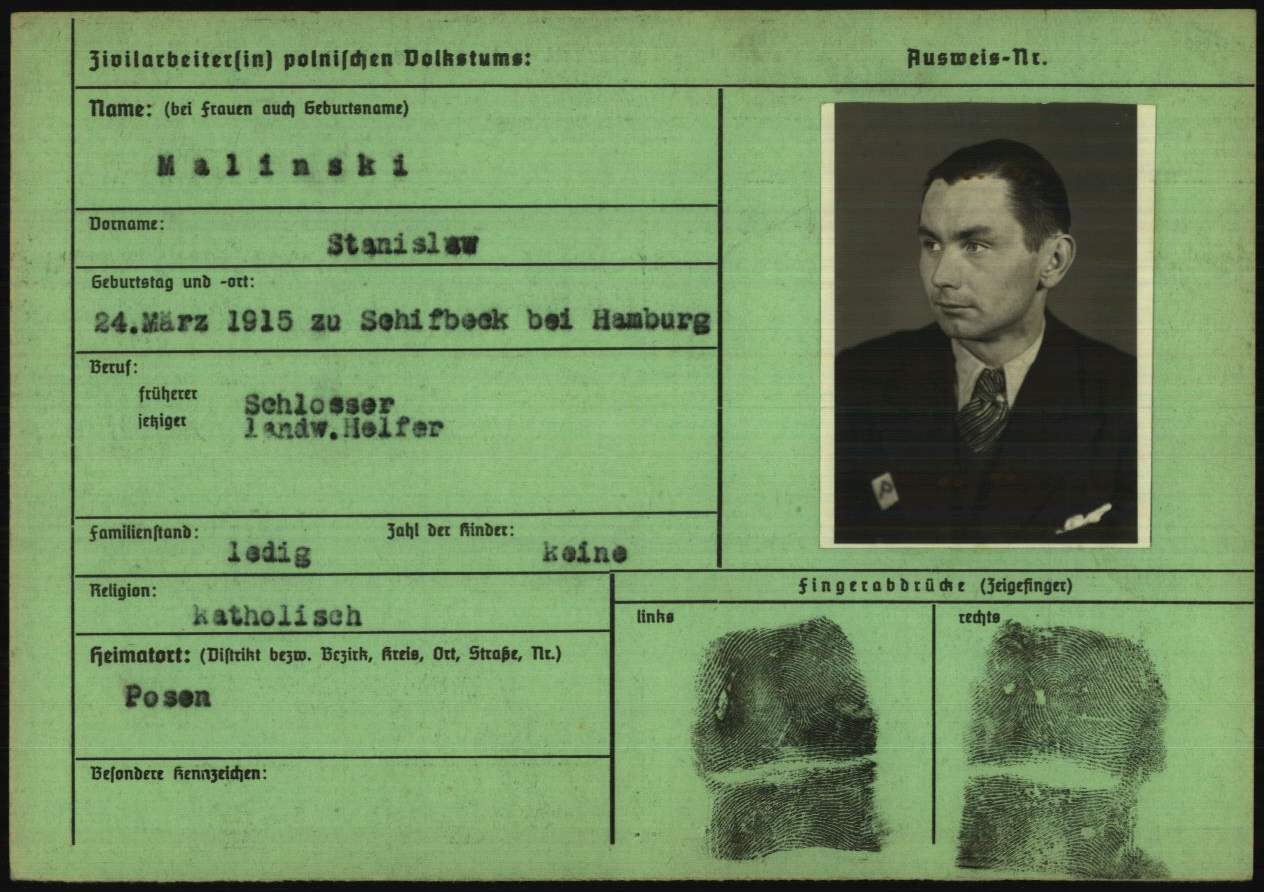

The German Ausländerpolizei (foreigner police) registered civilian forced laborers from the Soviet Union in special Ausländerkarteien (foreigner card files). It did the same for civilian laborers from Poland. Every city and county had a foreigner police office, also known as the Ausländeramt (foreigner office), that created two identical index cards for all Polish and Soviet civilian laborers who were registered there: one card was used by the foreigner police themselves at the county level. The other was sent to the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) (Reich Main Security Office) in Berlin. This enabled both offices to keep track of where the Polish and Soviet forced laborers were registered and tracked by the police.

The forms for Soviet forced laborers were yellow, while the cards for Polish forced laborers were printed on green paper. The two cards were identical in every respect except the name of the document. The foreigner police did not maintain a separate card file for civilian laborers from other countries who did forced labor in the German Reich.

The German Ausländerpolizei (foreigner police) registered civilian forced laborers from the Soviet Union in special Ausländerkarteien (foreigner card files). It did the same for civilian laborers from Poland. Every city and county had a foreigner police office, also known as the Ausländeramt (foreigner office), that created two identical index cards for all Polish and Soviet civilian laborers who were registered there: one card was used by the foreigner police themselves at the county level. The other was sent to the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) (Reich Main Security Office) in Berlin. This enabled both offices to keep track of where the Polish and Soviet forced laborers were registered and tracked by the police.

The forms for Soviet forced laborers were yellow, while the cards for Polish forced laborers were printed on green paper. The two cards were identical in every respect except the name of the document. The foreigner police did not maintain a separate card file for civilian laborers from other countries who did forced labor in the German Reich.

Questions and answers

-

Where was the document used and who created it?

Polish civilian forced laborers had to report to local police stations after the employment office had assigned them to a business. Every city and county had its own foreigner police agency, also known as Ausländeramt (foreigner office), which was situated in police headquarters and county administrations starting in 1940. All the civilian laborers from the Soviet Union who were registered in the city or county were entered in the foreigner card files, the Ausländerkarteien, maintained at this office. The police officers took down the personal details of the Soviet forced laborers and set up special index cards for them developed by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) (Reich Main Security Office). Two index cards with a photo and fingerprints were created for each civilian laborer. One card remained with the local foreigner police while the other was sent to the RSHA in Berlin. This office gathered information on the forced laborers in the entire German Reich in what was known as the Ausländer-Zentralkartei (central foreigner card file).

- When was the document used?

Foreign laborers were already being tracked by police stations using notification of residence before World War II began. After the German Wehrmacht invaded Poland in September 1939, thousands of Polish people were brought to Germany as forced laborers. A few months later, on March 8, 1940, the Reich government issued the Polenerlasse (Polish Decrees), which introduced discriminatory special laws for Polish civilian workers. From then on, they had to wear a “P” on a conspicuous location of their clothing. In addition, the foreigner police also logged them on their new green index cards. There were also separate cards for Soviet forced laborers starting in 1941.

The foreigner police continued to issue the index cards until the end of the war. Their only concession was to stop issuing and mailing the second index card to the Reichssichereitshauptamt (RSHA) (Reich Main Security Office) in Berlin in late 1943. Allied bombing raids had destroyed the RSHA’s central card file, and so it was not continued.

- What was the document used for?

Foreign laborers were officially monitored by county foreigner police agencies and by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) (Reich Main Security Office) in Berlin. Photographs and fingerprints on the front of the cards allowed them to identify the civilian laborers. Furthermore, the police were quickly able to determine the person’s whereabouts since the backs of the cards also identified the company where the person had been forced to work.

The cards had to be up-to-date at all stations, even if the forced laborers were transferred to another company. This was done though the employment offices, which reported the change to the local police station. The police station then had to inform not only the RSHA by postcard, but its county foreigner police as well. If the forced laborers moved to another county, the foreigner police now responsible for them requested the index card along with other documents and in turn informed the RSHA about the individual’s new place of work. The foreigner police agencies at the person’s former place of work placed a blank card without a photograph in their catalog, on which they noted the change.

If civilian forced laborers were transferred to a Gestapo Arbeitserziehungslager (AEL) (labor reeducation camp) or concentration camp, all the associated records were kept by the foreigner police agency responsible for the county where the workplace was located. Here, the staff noted the individual’s incarceration and waited until they were released and reassigned to a job. Civilian laborers did not return from the concentration camps, though; they remained in custody until they died or were liberated. If forced laborers returned to their countries of origin – which was done in the first years of the war if they were seriously ill or pregnant – the card remained with the foreigner police agency that was last responsible for them.

- How common is the document?

Theoretically, all Polish civilian forced laborers in the German Reich had two green index cards issued by the immigration police. That means two index cards must have been issued for every one of about 1.6 million people. The central card file of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RHSA) (Reich Main Security Office) in Berlin, where one of the two cards was kept, was destroyed in air raids at the end of 1943. However, not all the index cards set up by the county foreigner police were preserved, either. Some were lost during wartime air raids or deliberately destroyed to cover up the traces of forced labor.

It is not known how many foreigner police index cards came to Arolsen after the war. The staff of the International Tracing Service (ITS), the predecessor to the Arolsen Archives, placed the cards in the Kriegszeitkartei, the wartime card catalog, along with many other documents. This catalog comprises a total of approximately 4.2 million documents. That makes it impossible to say how many foreigner police index cards are currently kept in the Arolsen Archives, either as originals or copies.

- What should be considered when working with the document?

The Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) (Reich Main Security Office) dictated exactly how to fill out the foreigner police index cards. The local police authorities were to report all changes immediately to both the county foreigner police and the RSHA. Some of the index cards preserved in the Arolsen Archives are nevertheless incomplete. Especially in the last months of the war, the final phase, information on laborers’ whereabouts was either not updated at all or, if so, noted only in a very abbreviated form.

The cards usually contain only the start of the civilian worker’s employment, not the end. This was only noted on the index cards if the person was sent back home for reasons such as pregnancy or inability to work, which was done in the beginning. After the liberation by the Allies, the forced laborers were not formally deregistered with the local German police. Either they returned directly to their home countries or registered as Displaced Persons (DPs). The registration documents issued by the German authorities for forced laborers during the war were not continued but rather were replaced by the Allies’ own documents such as the DP 2 Cards.

If you have further information about this document, we would be delighted to hear from you at eguide@arolsen-archives.org. The document descriptions in the e-Guide are regularly updated – and the best way to do that is by gathering knowledge together.

Help for documents

About the scan of this document <br> Markings on scan <br> Questions and answers about the document <br> More sample cards <br> Variants of the document