Page of

Page/

- Reference

- Intro

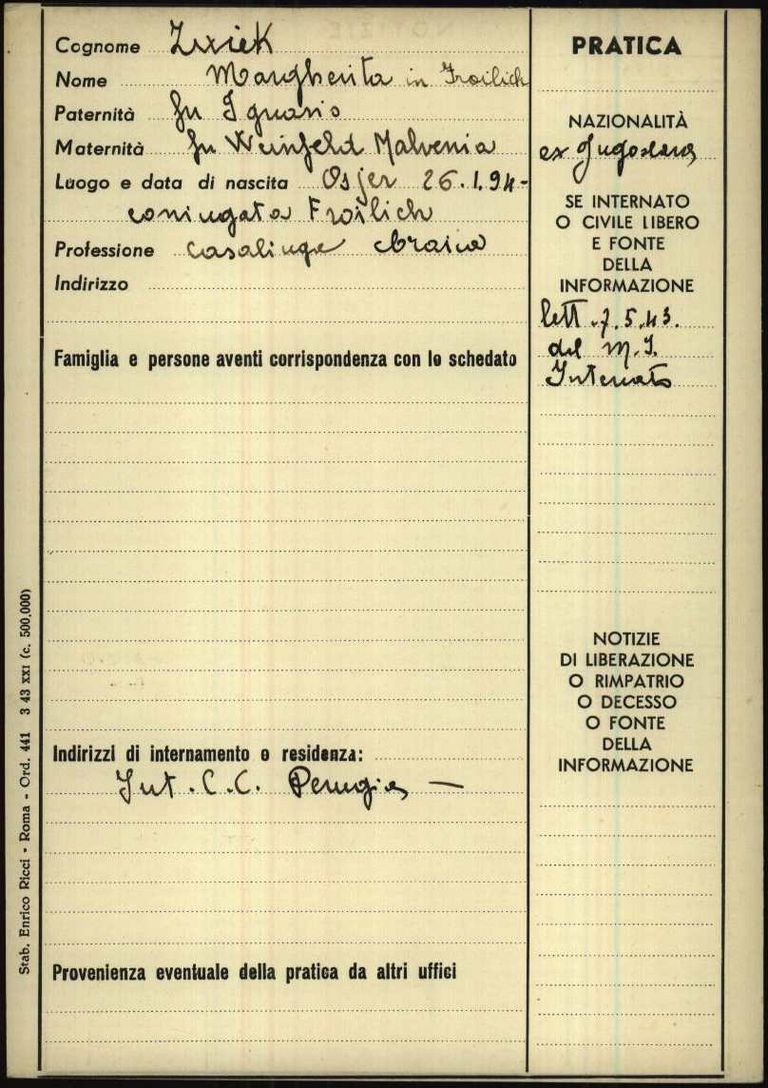

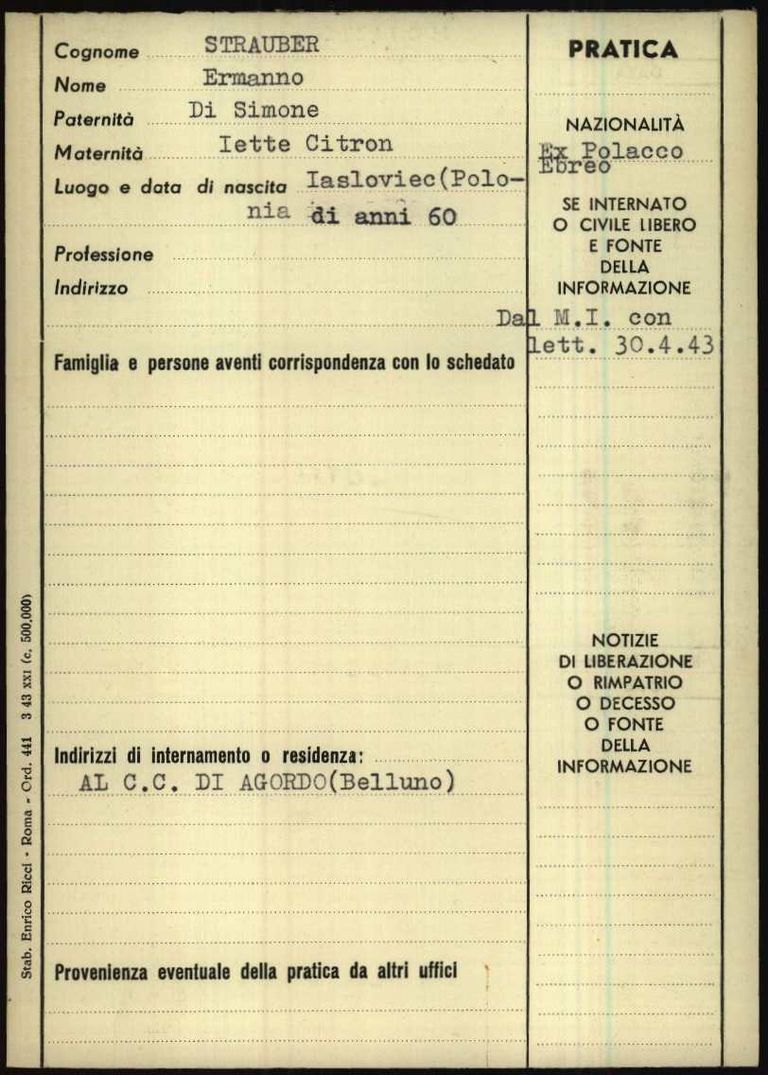

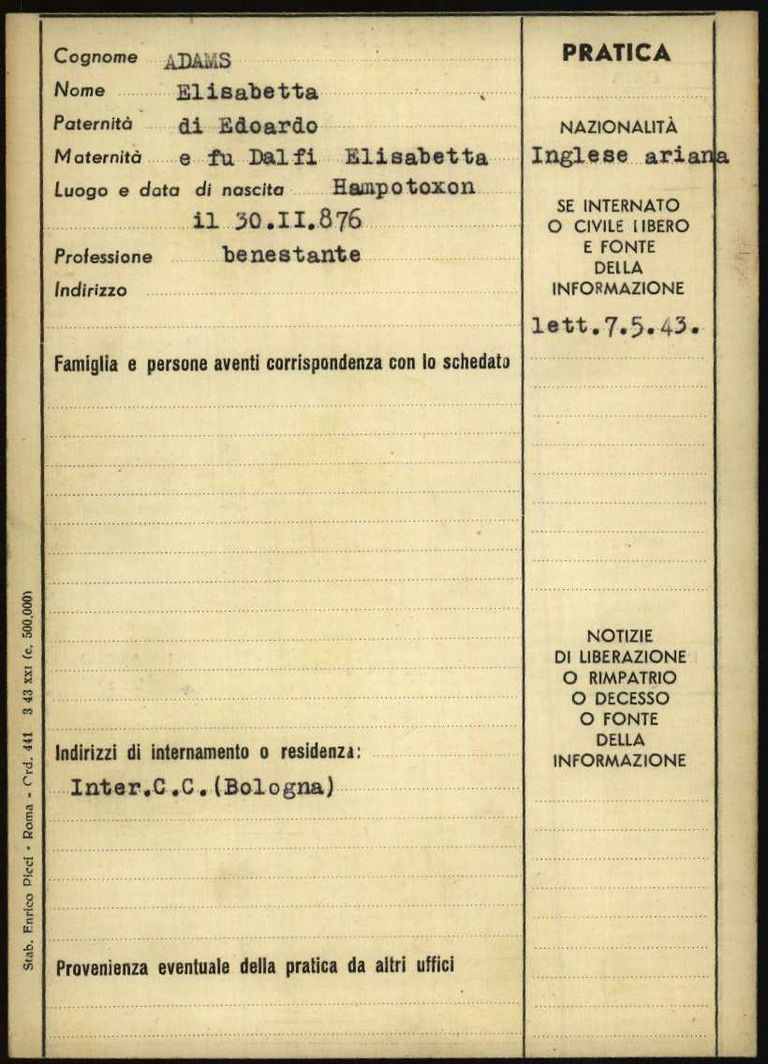

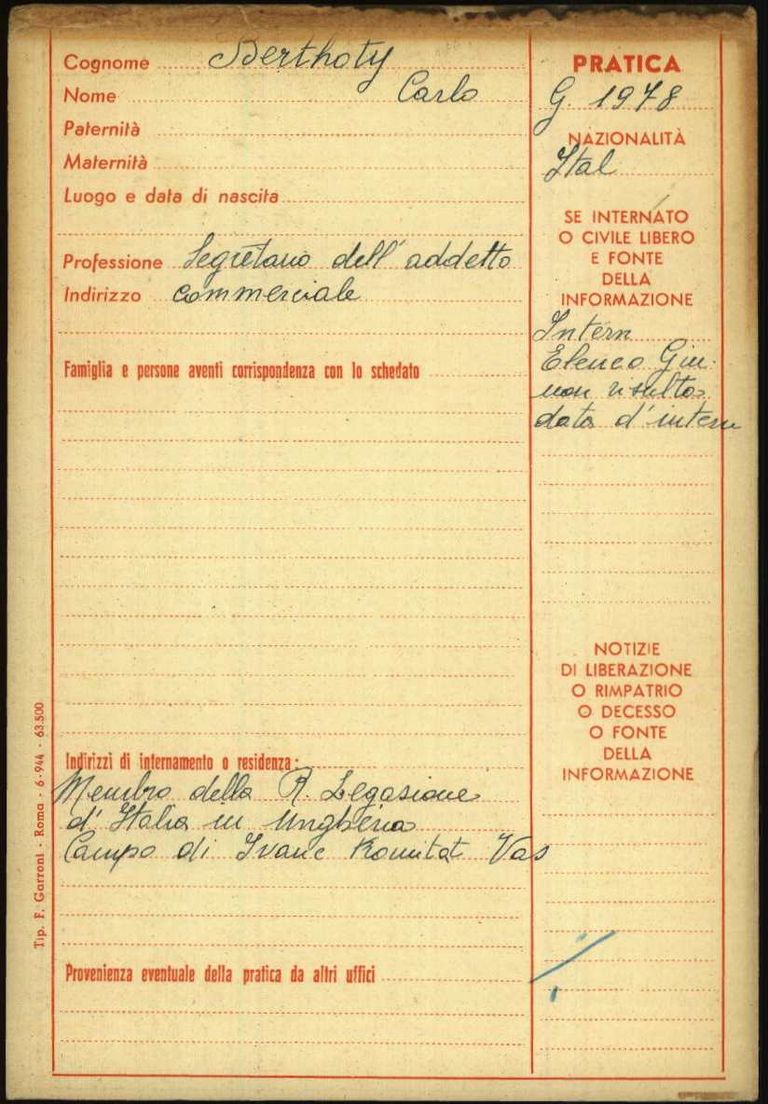

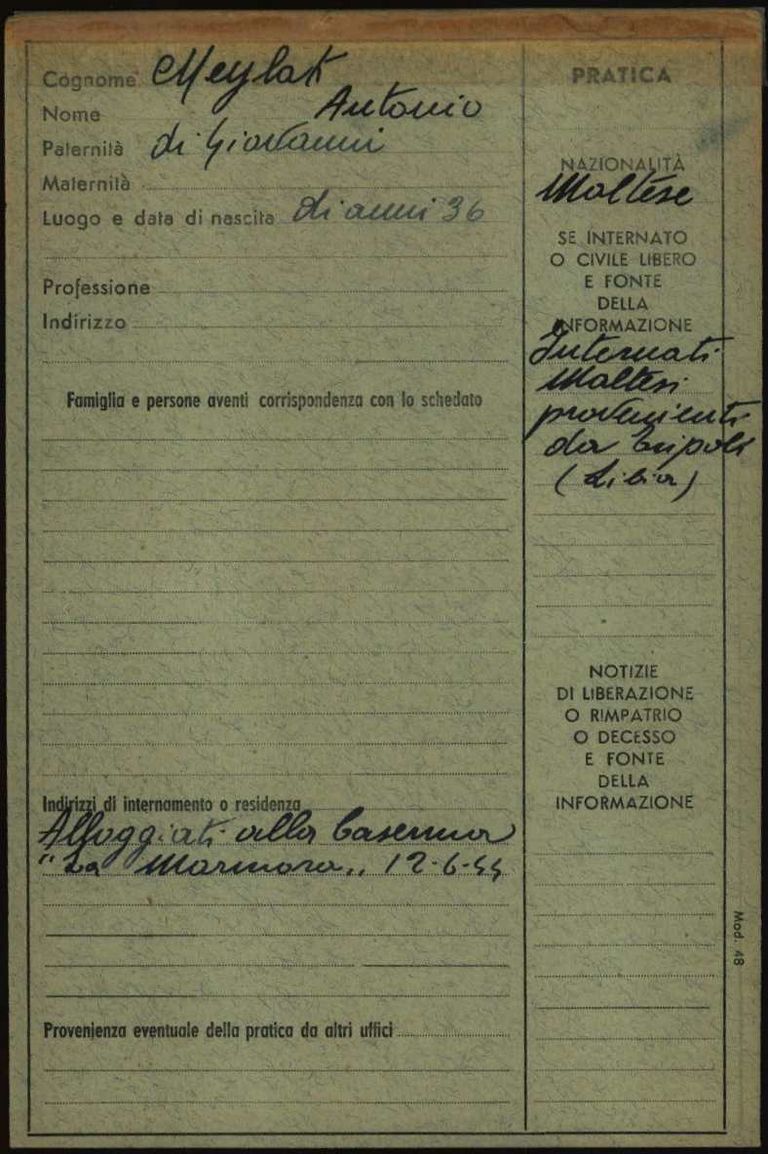

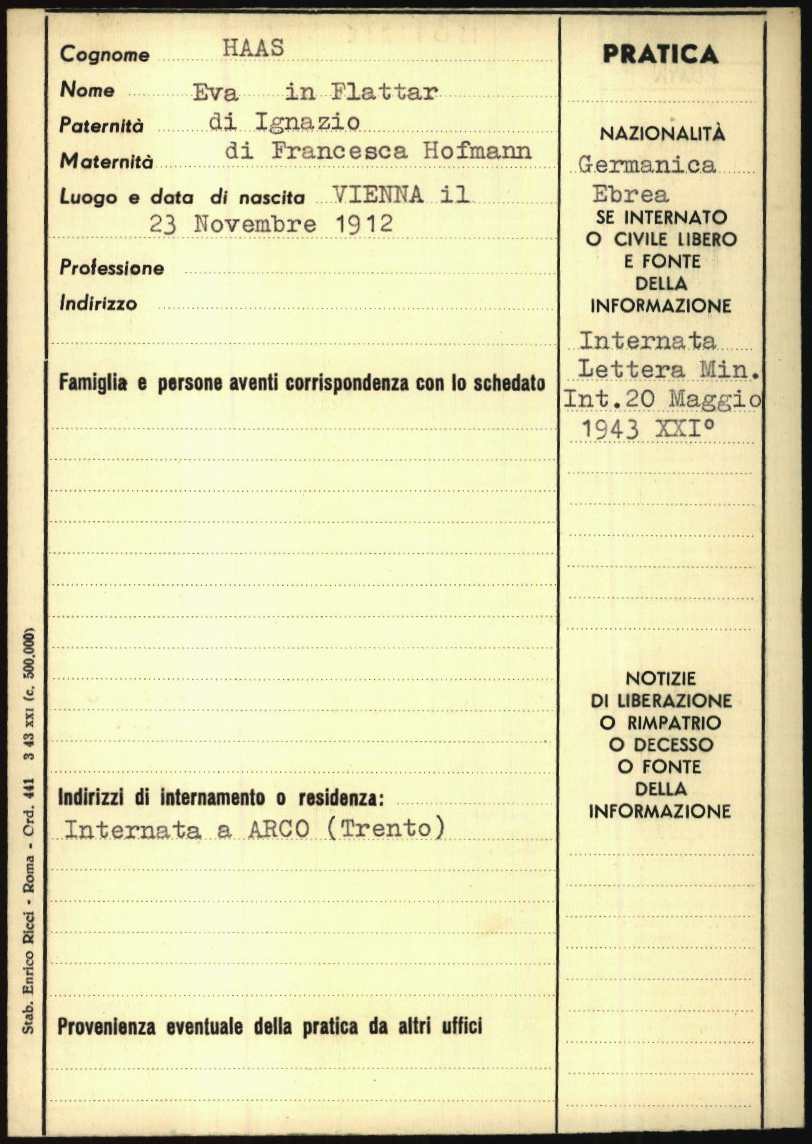

These file cards were used by the Italian Red Cross to manage the addresses of foreigners interned in Italy. The cards could be typed or filled out by hand. The same cards were used for Jewish and non-Jewish foreigners, and the internee’s precise nationality was noted in the field marked Nazionalità. The cards are all the same, regardless of whether the individuals were held in an internment camp or forced to reside in villages outside of a camp as so-called “free internees.”

These file cards were used by the Italian Red Cross to manage the addresses of foreigners interned in Italy. The cards could be typed or filled out by hand. The same cards were used for Jewish and non-Jewish foreigners, and the internee’s precise nationality was noted in the field marked Nazionalità. The cards are all the same, regardless of whether the individuals were held in an internment camp or forced to reside in villages outside of a camp as so-called “free internees.”

Questions and answers

-

Where was the document used and who created it?

The collection of cards known as the Italian card file at the Arolsen Archives was put together by the Italian Red Cross (Croce Rossa Italiana, CRI) based in Rome. The CRO office for prisoners of war (Ufficio Prigionieri di Guerra or Ufficio Prigionieri Ricerche e Servizi Connessi) used the cards to determine the location of Jewish and non-Jewish foreigners – as well as some Italian citizens – who had been interned in Italy. The cards came with correspondence folders, some of which have been preserved in the Arolsen Archives. These folders hold the letters exchanged between the Italian Red Cross and Italian ministries, municipalities and the heads of internment camps. There is also correspondence with national Red Cross organizations and the International Committee of the Red Cross. Individuals could contact their national Red Cross organization to find out if there was any information about interned friends or family members. The Italian Red Cross would then respond to these inquiries using the documents available. In these letters, people asked specifically about the location of internees or requested that letters and packages be delivered. After the war, more letters were added to the folders, some of which were exchanged with the Jewish communities of Italy.

In most cases, information about where a person was interned came from the Italian Ministry of the Interior. The employees of the CRI abbreviated this on the cards to Min. Int. in the right-hand column, which indicated the source of the information (Italian: fonte della informazione). The Ministero dell’Interno had its own department for the administration of the internment camps, known as the Office for Demographics and Race. This department would send a letter to the Italian Red Cross – usually upon request – to notify it of the location of the required person. Red Cross employees would then write or type this location on the cards in the Italian file, together with a reference to the letter.

- When was the document used?

These largely identical forms were kept for Jewish and non-Jewish foreigners who were interned in an Italian camp, a police station or another location during World War II. There are a few cards for Italian citizens as well, but these are rare exceptions. For most people, their last known location was noted prior to September 1943, before German troops invaded northern and central Italy. In general, most of the entries come from the summer of 1943, specifically between May and August 1943. However, the folders at the Arolsen Archives also include letters from after the war. This suggests that the folders continued to be used, but the cards were not always updated. Since the Italian card file, including the correspondence folders, reached the ITS in 1956, all of the entries must have been made before then.

- What was the document used for?

From 1922, Italy was ruled by the Fascist Prime Minister Benito Mussolini. He and Hitler emphasized the close connection between Germany and Italy, and he began speaking of a “Rome–Berlin axis” in 1936. In July 1943, Mussolini was deposed and arrested, and Italy concluded a separate peace treaty with the Allies. German troops then occupied central and northern Italy. After Mussolini was freed from prison by the Germans, he was initially able to continue ruling in southern Italy.

Until this point, Italy had been allied with the German Reich and had supported its anti-Jewish policy. Consequently, anti-Jewish laws were also introduced in Italy in 1938, which put restrictions on around 46,000 Jews living in the country at the time. From 1940, 50 to 100 internment camps were set up for political opponents, non-Jewish foreigners and around 3,900 foreign Jews living in Italy. Their internment could take different forms. There were large barracks camps, such as the one in Farramonti di Tarsia, but people were also detained in individual apartments or houses. It was also possible for so-called “free internees” to live under strict restrictions in a locality outside of a camp. This distinction is reflected on the cards in the Italian card file. The abbreviations Int. C.C. and C.C. stand for campo di concentramento (literally: concentration camp), while locations with no additional information or the note Comune indicate “free internment.”

Despite the close political connections between Italy and Nazi Germany, thousands of European Jews had fled to Italy before the invasion of German troops in 1943 in order to plan their emigration from there. 5,000 non-Italian Jews were able to escape the Nazis in this way, but others were interned and fell into German hands after the change of power. When Italy joined the war in 1940, Jews from territories occupied by the Italian army were affected as well. As a result, around 2,780 Jews from Yugoslavia, 200 from Albania, 300 from Libya and 500 from Rhodes were also arrested and interned in Italy. All of these developments explain the many different nationalities represented in the Italian card file. Along with Jewish internees, foreigners were also taken to internment camps if they were citizens of a nation not allied with Italy. This meant that there were also internees from Slovenia, England, France and America who had been in Italy when the war broke out, arrived in Italy during the war or fell into Italian hands during the fighting. Employees of the Italian Red Cross also created cards for these people so that they could verify where they were at a certain point in time. The Arolsen Archives do not have any cards from the Italian card file for Jews who had been born in Italy and/or had Italian citizenship, but folders for these individuals have been preserved.

- How common is the document?

The Arolsen Archives have around 15,000 cards that are part of the Italian card file. Most of the cards are white, but there are also green cards and white cards with red writing. The cards with red writing are very rare and were probably created predominantly, but not exclusively, for non-Jewish Italian citizens. It is not yet clear whether the green cards represent a specific category of internees. It is notable, however, that most – though not all – of them were used for internees from Malta.

- What should be considered when working with the document?

The cards from the Italian card file for Jewish and non-Jewish internees represent the status of these individuals at a particular point in time. The cards do not reveal the people’s path of persecution prior to their internment, such as where or when the person was arrested. Because the cards were also not changed or updated (with very few exceptions), it is not possible to determine on the sole basis of the cards what happened to the person after their card was created.

It is also important to remember that the cards often use the Italian form of a name, which was not always how the name was actually written. For example, Alfred Meyer is referred to as Alfredo Meyer on his card, and his father Hermann is named Ermanno. Other variations include Giglielmo for Wilhelm, Manfredo for Manfred, Gustavo for Gustav and Gisella for Gisela. This should be taken into consideration, even though the alphabetical-phonetic system of the Arolsen Archives' database accounts for all of these variations and bundles together international versions of names.

It is also notable that there are numerous folders but only a small number of file cards for prisoners with Italian citizenship. Conversely, in some cases the card indicates that a folder should exist for a person even if it doesn’t. Furthermore, many of the folders stored at the Arolsen Archives are now empty and consist only of the envelope.

If you have any additional information about this document or any other documents described in the e-Guide, we would appreciate it very much if you could send your feedback to eguide@arolsen-archives.org. The document descriptions are updated regularly – and the best way for us to do this is by incorporating the knowledge you share with us.

Help for documents

About the scan of this document <br> Markings on scan <br> Questions and answers about the document <br> More sample cards <br> Variants of the document