Page of

Page/

- Reference

- Intro

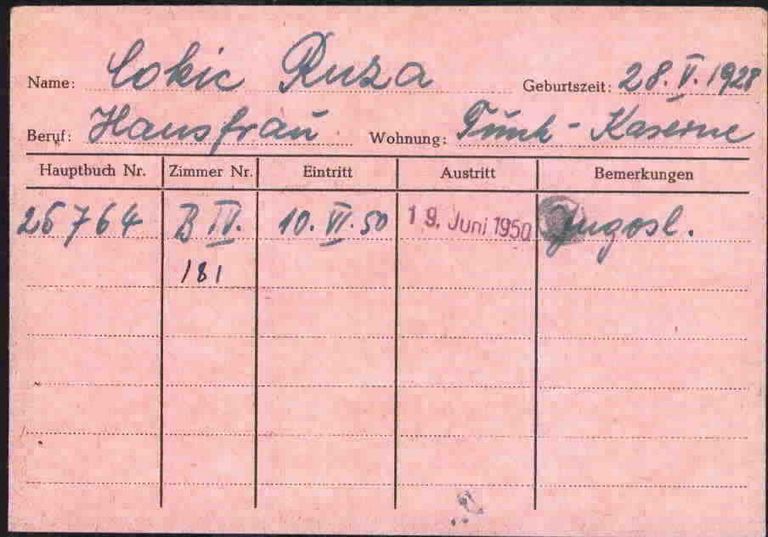

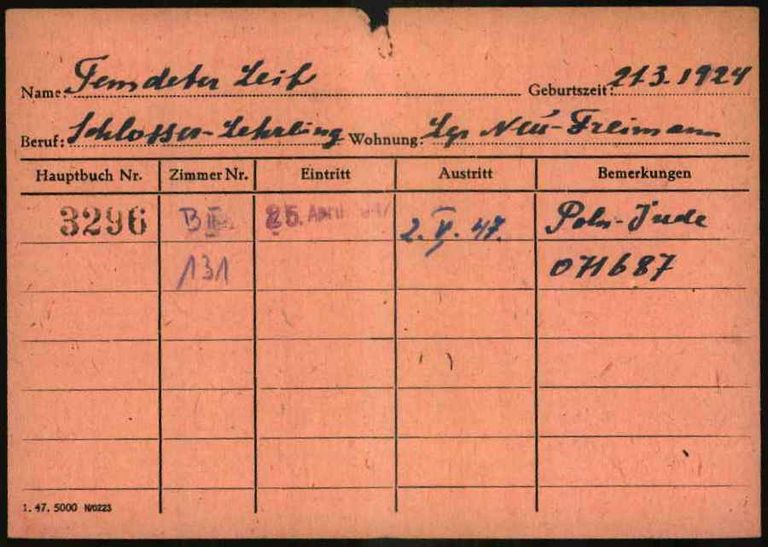

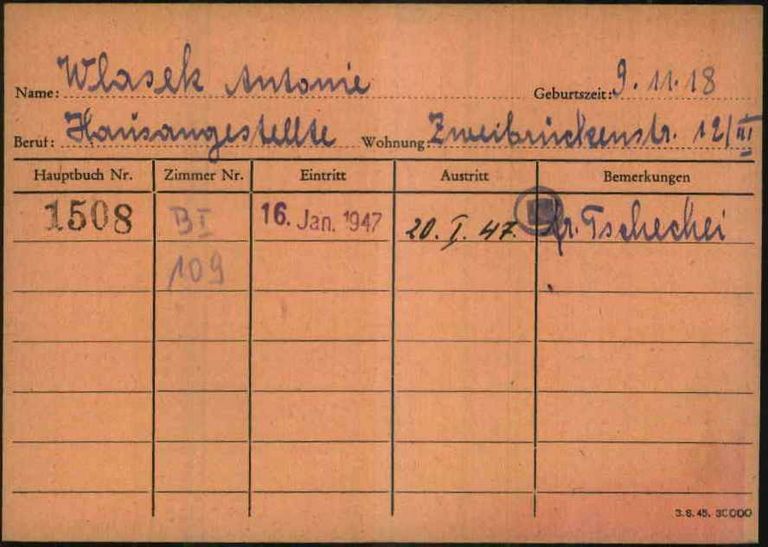

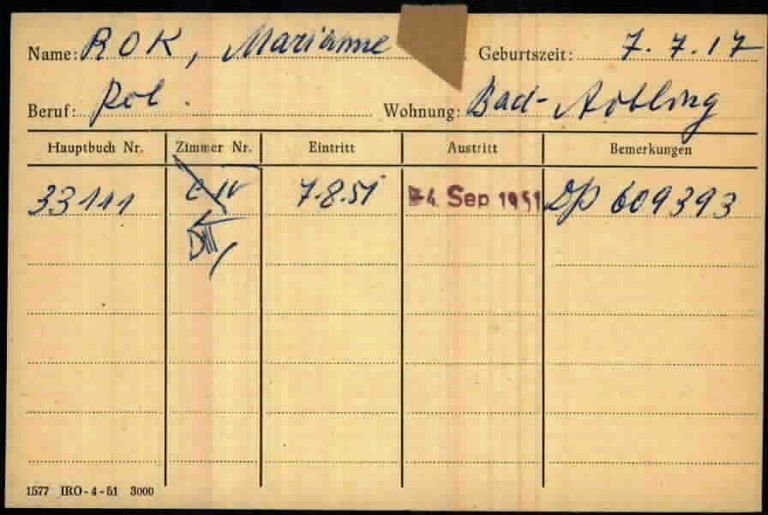

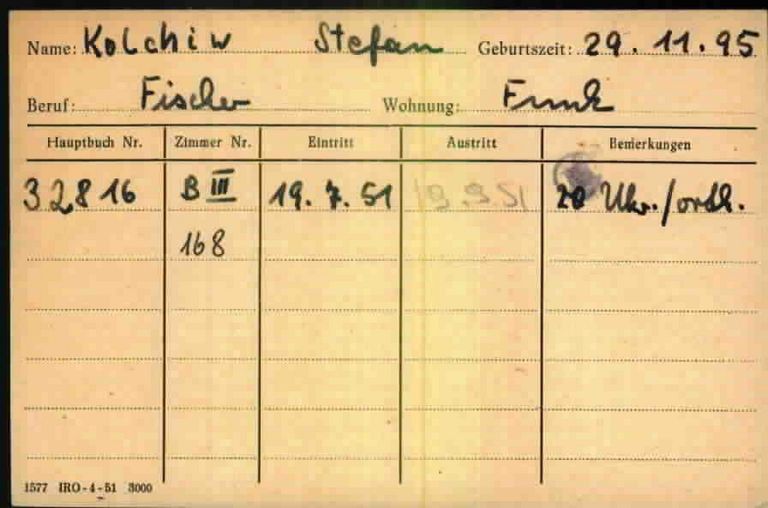

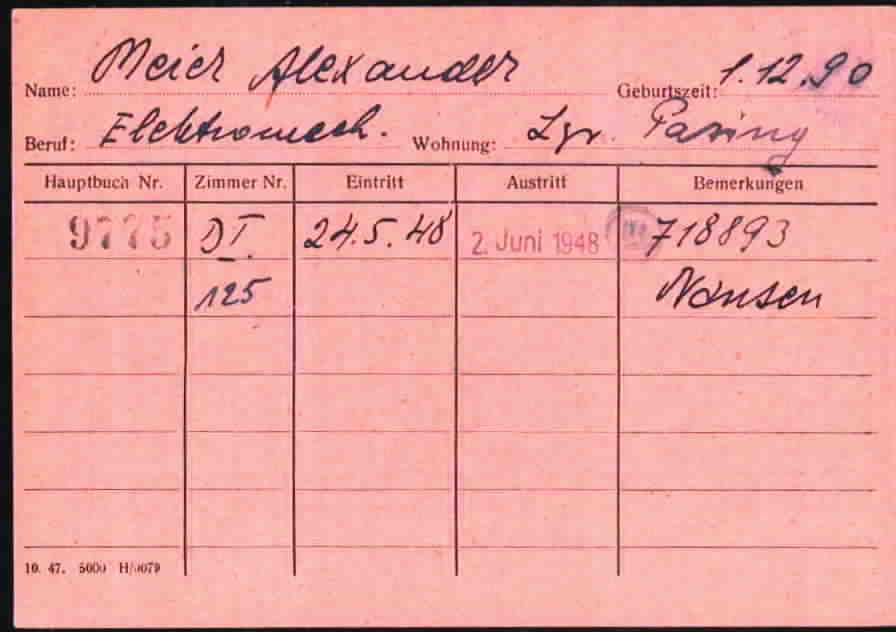

In order to care for sick DPs, the US Allies established a DP hospital in a former nursing home in Munich-Schwabing in July 1945. The employees there created an index card for every patient, on which they noted the person’s room number and how long they had stayed at the hospital. This card, which ITS employees referred to as “hospital card,” was printed on pink, orange or yellow paper. If a card like this exists, it means the person named on the card was treated in Munich-Schwabing.

In order to care for sick DPs, the US Allies established a DP hospital in a former nursing home in Munich-Schwabing in July 1945. The employees there created an index card for every patient, on which they noted the person’s room number and how long they had stayed at the hospital. This card, which ITS employees referred to as “hospital card,” was printed on pink, orange or yellow paper. If a card like this exists, it means the person named on the card was treated in Munich-Schwabing.

Questions and answers

-

Where was the document used and who created it?

These documents, known as “hospital cards” at the ITS and Arolsen Archives, come from the DP hospital in Munich-Schwabing. After the war, DPs required special medical care. Many DP camps had their own infirmary, but more serious cases were treated in specially established DP hospitals. For example, there was a sanatorium in Gauting for people with tuberculosis and other lung diseases, and there was a mental hospital in Wiesloch for mentally ill DPs. Additionally, from March 1946 to January 1952, DP children and infants were treated in the Heckscher Children’s Clinic in Munich.

In Munich-Schwabing, DPs were initially treated at the municipal hospital. 200 beds were reserved for them there by order of the Allies. But by July 1945, the occupying power had taken over the entire hospital and handed over responsibility for it to UNRRA. The DP patients were then housed in a former nursing home near the clinic – which is why it was referred to as the “Altersheim” (nursing home) DP hospital. The IRO was responsible for providing care there from 1947 until the hospital for DPs was closed in 1951, after which only American occupying soldiers continued to be treated there.

In the DP hospitals, German doctors and nurses worked alongside Jewish and non-Jewish DPs. Even employees of Allied aid organizations such as UNRRA and later the IRO and AJDC were involved in providing care. Furthermore, special courses were offered to train DPs as assistant nurses, for example. It is not possible to say exactly who of them filled out the “hospital cards” when a patient was admitted, however.

- When was the document used?

The earliest card examined thus far was created in March 1946. The latest card is dated September 1951. Most cards do not come from the immediate postwar period but from the years in which the IRO was responsible for caring for DP patients. This means there are many cards from between 1947 and 1951. It is not possible to say whether no cards were created prior to this, or whether these early cards have simply not been preserved.

- What was the document used for?

The cards were filled out together with other documents presumably when patients arrived at the DP hospital in Munich-Schwabing. The employees noted who was being treated in which room of the hospital. The cards reveal just how diverse the group of DP patients was. There are cards for Ukrainians, Yugoslavians, Hungarians, Poles and Latvians. Jews were treated alongside the other patients. The patients in Munich-Schwabing came from the DP camps in Bad Aibling, Föhrenwald and Fischbach, among others – all of which were near Munich. So-called free-living DPs who resided in private accommodations instead of a camp can also be identified by the cards: instead of the name of a camp, their place of residence is listed as a private address with a street.

In addition to the German-language cards, the Munich-Schwabing DP hospital also used English cards with a slightly different design which asked for other information. These cards had fields for the patients’ diagnosis, their next of kin and their marital status. The handwriting reveals that these cards were issued together with the “hospital card” by the same person. As far as researchers have been able to determine, the different paper colors do not mean anything.

- How common is the document?

ITS employees sorted the “hospital cards” following an alphabetical-phonetic system and filed them together with a total of 3.5 million other DP documents in the postwar card file (Nachkriegszeitkartei, Collection 3.1.1.1). This means it is not possible to say exactly how many cards from patients of the DP hospital Munich-Schwabing have been preserved in the Arolsen Archives. However, the print runs that can be found on some cards suggest that the cards were numerous: 30,000 cards were printed in August 1945, 3,000 in August 1946, 5,000 each in January and October 1947, 3,000 in April 1951, and another 2,000 in July 1951. These numbers are huge and could indicate that the cards were not only used in Munich-Schwabing but also in other DP hospitals. However, all of the cards preserved in the Arolsen Archives come from the Munich-Schwabing hospital.

- What should be considered when working with the document?

Looking at the “hospital cards,” it is notable that patients stayed in the Munich-Schwabing hospital for relatively short periods of time. Most DP patients were there for just a few days to a maximum of a few weeks. This is because the cards come from a period when medical care was no longer as urgent as it was immediately after prisoners were liberated from forced labor and concentration camps. In other facilities, such as the lung sanatorium in Gauting, the DP patients stayed much longer. Unlike at the clinic in Munich-Schwabing, a community formed at the sanatorium, with cultural and educational programs just like in the DP camps.

In addition to the “hospital card” from Munich-Schwabing, other medical files for people can also be found in the Arolsen Archives. They are often stored together with their CM/1 folders. This is because, in order to request support from the IRO, DPs had to submit medical documents along with their CM/1 applications.

If you have any additional information about these cards, we would appreciate it very much if you could send your feedback to eguide@arolsen-archives.org. New findings can always be incorporated into the e-Guide and shared with everyone.

Help for documents

About the scan of this document <br> Markings on scan <br> Questions and answers about the document <br> More sample cards <br> Variants of the document