Page of

Page/

- Reference

- Intro

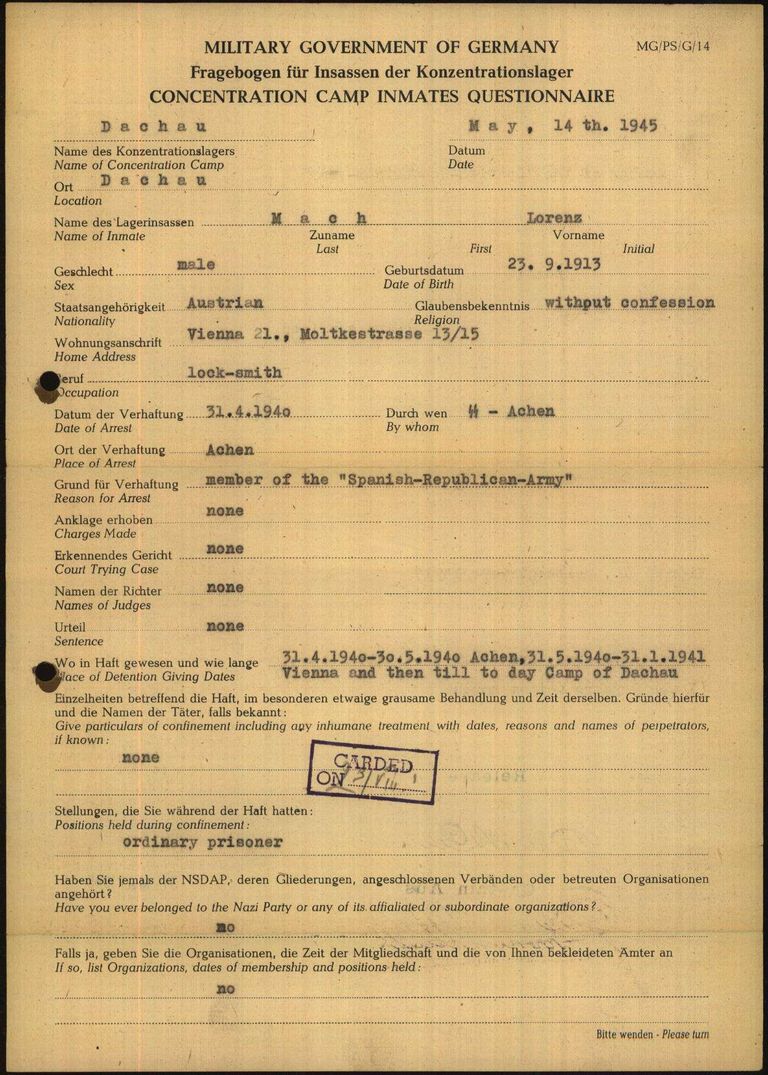

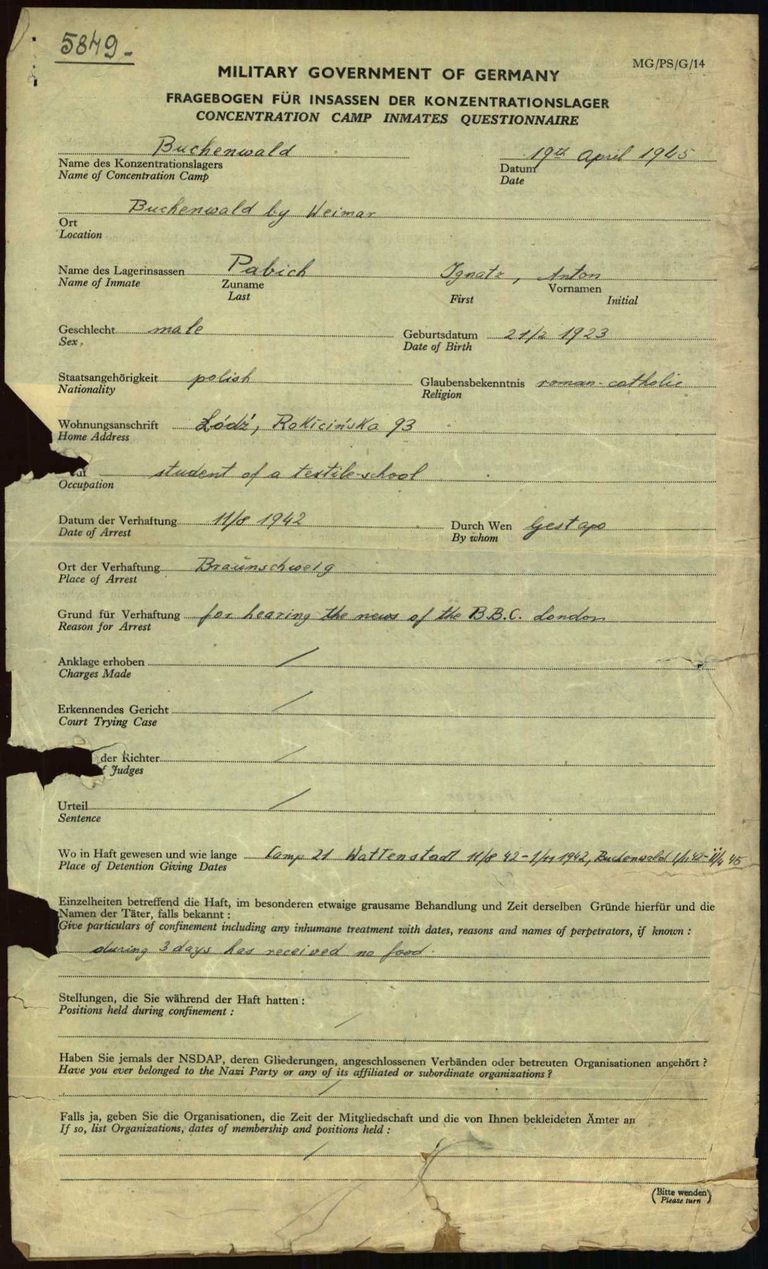

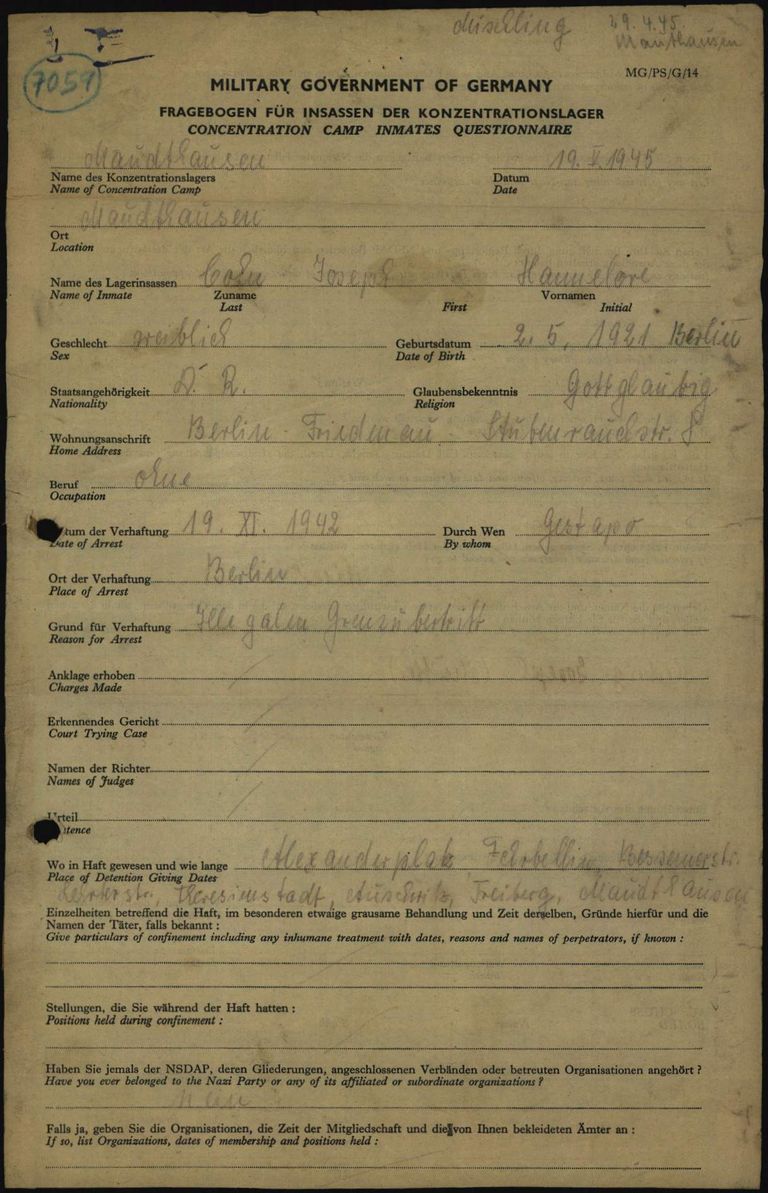

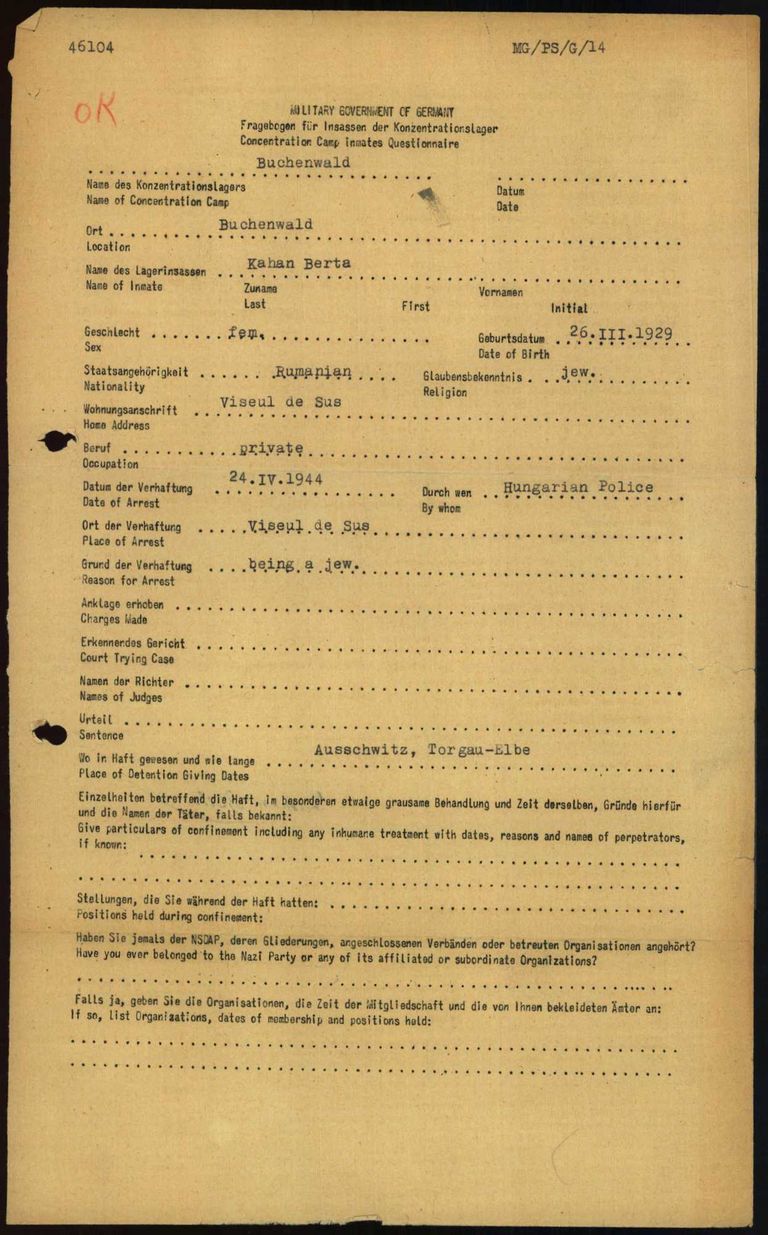

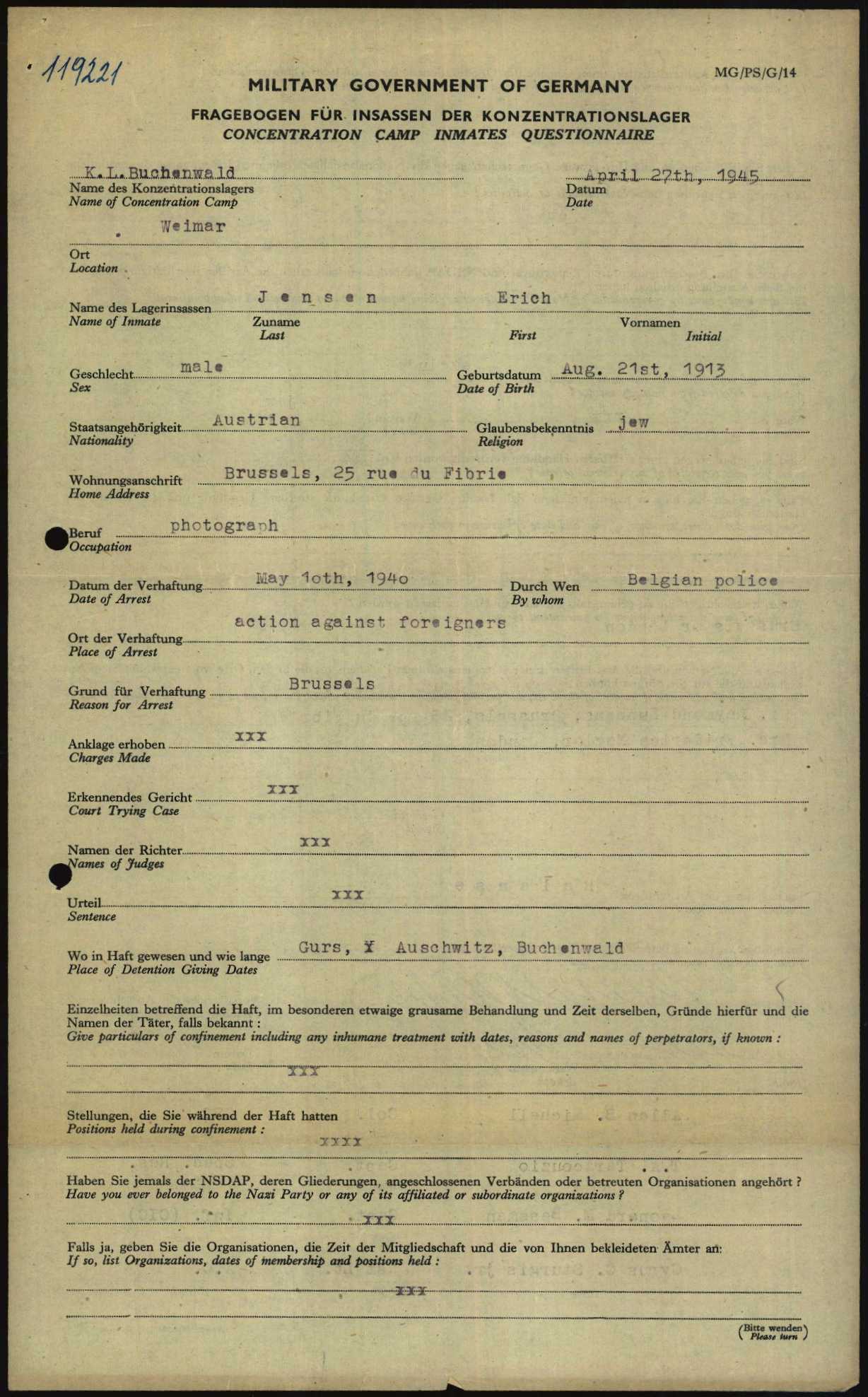

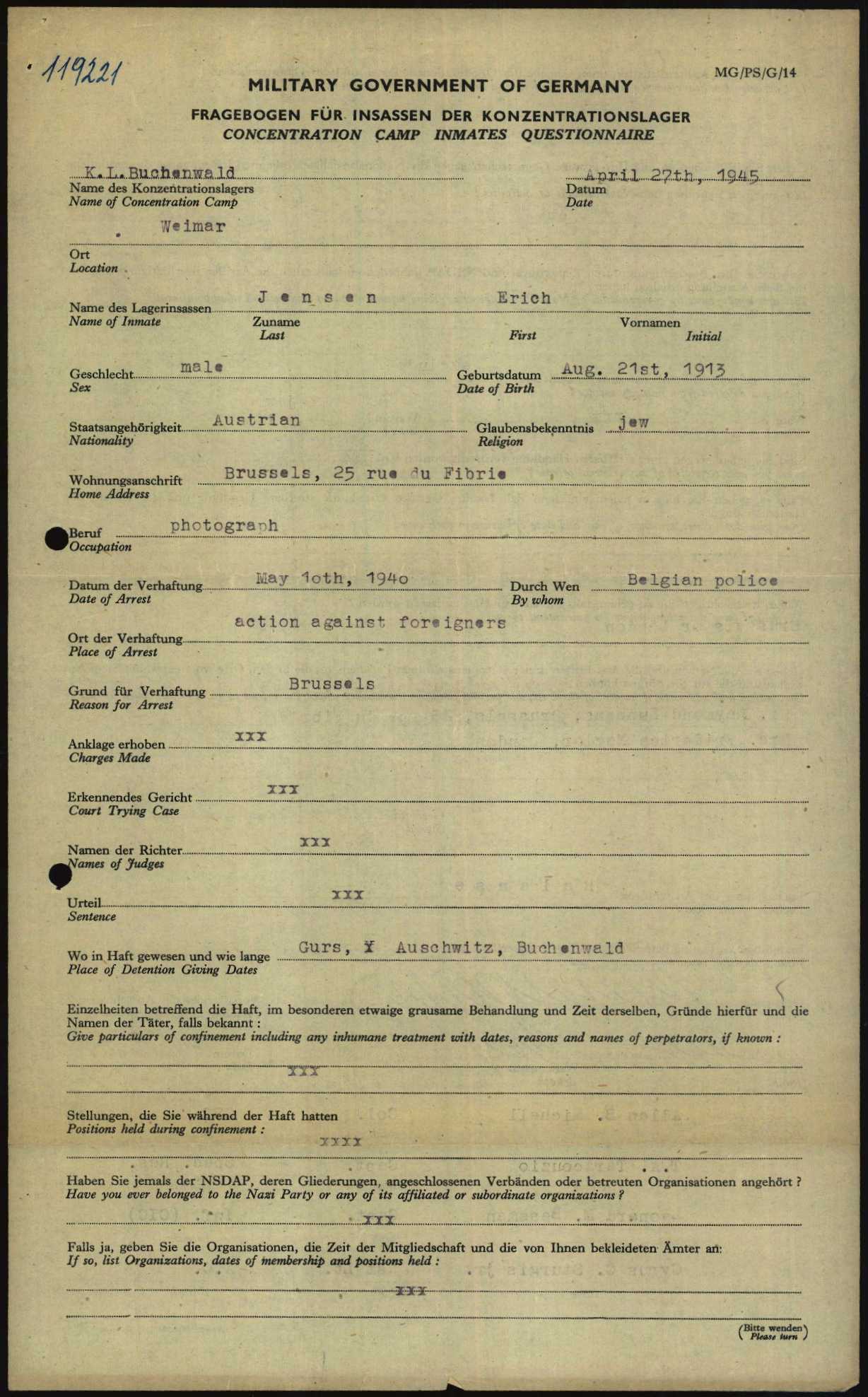

The official name of this document is the Concentration Camp Inmates Questionnaire. The US Army produced these forms for prisoners from the concentration camps they had liberated. The forms are therefore all very similar, regardless of whether they were handed out in the liberated Dachau, Buchenwald or Mauthausen camps. These questionnaires exist for both male and female prisoners. Although instructions had been issued to fill out the questionnaires on a typewriter, some of the forms that have been preserved were filled out by hand. Additionally, the typeface on the pre-printed forms can sometimes vary slightly, though this has no bearing on the form’s content.

The official name of this document is the Concentration Camp Inmates Questionnaire. The US Army produced these forms for prisoners from the concentration camps they had liberated. The forms are therefore all very similar, regardless of whether they were handed out in the liberated Dachau, Buchenwald or Mauthausen camps. These questionnaires exist for both male and female prisoners. Although instructions had been issued to fill out the questionnaires on a typewriter, some of the forms that have been preserved were filled out by hand. Additionally, the typeface on the pre-printed forms can sometimes vary slightly, though this has no bearing on the form’s content.

Questions and answers

-

Where was the document used and who created it?

When the concentration camps were liberated, the Allies found more than a quarter of a million weakened prisoners who needed food and medical attention. Structures also had to be established so that these former prisoners could return to their homes or emigrate to another country. The Military Government of Germany, the highest US Army authority, introduced a decisive formal step for regulating the prisoners’ release: all prisoners liberated from a concentration camp by US troops were supposed to fill out a questionnaire. Since the sub-camps had already been dissolved (with very few exceptions), the questionnaires were given to the liberated prisoners in the main camps. They were distributed by the national camp committees that the prisoners themselves had officially established immediately after the liberation. Since the questionnaires had to be filled out in English, the former prisoners often helped one another as translators. Based on these questionnaires, a military board of review would decide whether the liberated prisoners should be officially released or remain in custody. One of the main goals of the US authorities was to find war criminals and prisoners with a Nazi past. These individuals were supposed to be transferred to ordinary prisons or camps for prisoners of war.

- When was the document used?

The questionnaires were printed in Paris in April 1945. This meant that they could usually be distributed shortly after a camp was liberated. In Dachau, for example, the first forms arrived on May 2, 1945, and around 400 of them were filled out each day. One of the earliest forms from Buchenwald was filled out on April 16, 1945, just five days after US troops had reached the camp. However, there were never enough forms to go around, so people had to wait for new copies to arrive. In general, the liberated prisoners had to be patient. Hans Carls, a priest interned in Dachau, recalled: “The prisoners were very nervous because they had been promised that they would be released in the near future. Many believed that they would be released in the next few days. But the Americans took their time. After a few days, the individual [national] committees distributed questionnaires to their members. These questionnaires had to be filled out in English. This naturally made the whole affair take much longer, because there were not enough interpreters available” (Hans Carls: Dachau: Dokumente zur Zeitgeschichte II, Cologne 1946, pp. 209f.). Additionally, the questionnaires were officially supposed to be filled out on a typewriter, which led to further delays.

Based on the dates written on the questionnaires by the prisoners in Buchenwald, for example, it appears that most of the forms were filled out in the last week of April. The boards of review that would use the questionnaires to officially decide whether to release a prisoner finally convened in May and June 1945. The release process took different amounts of time in different camps. In Flossenbürg, the screening was completed before the quarantine period had passed. In Buchenwald, the board sessions, as they were known, ended on June 25, 1945. By that point, the boards had made decisions on the release of 3,781 people of different nationalities. In Dachau, the questionnaire process ended for many prisoners on May 12, 1945. From that point on, only liberated German and Austrian prisoners were required to fill them out.

- What was the document used for?

Many history books and personal accounts of concentration camp survivors end with the liberation of the camps. But in most cases, the arrival of Allied troops did not mean that the former prisoners immediately left the camps. First, leaving the camps was still prohibited, and second, the camps were placed under quarantine to prevent the spread of diseases such as typhus. Nonetheless, some prisoners made their own way back to their homes. Others stayed in the camps because they needed support, did not know where to go, or were too sick or weak to leave.

The international committees established by the prisoners themselves were responsible for organizing everyday life during this transition period. Many of the committees, which were made up of prisoners of all nationalities, had been formed even before the liberation. They organized the work in the kitchen and the clinic, for example. They also conducted daily roll calls and punished prisoners who had collaborated with the Germans. Additionally, they were responsible for distributing the questionnaires to the prisoners; prisoners of all nationalities and prisoner categories received the same form.

The liberated prisoners filled out the forms with the support of fellow prisoners who acted as translators. The forms were then given to the board of review. In a letter from May 1, 1945, the camp elder of Dachau wrote: “The conscientious, thorough and absolutely unambiguous completion of the questionnaire is an essential prerequisite for speedy settlement and thus release from Dachau concentration camp. Anyone who does not fill out a questionnaire will not be released. […] Only those who have received properly issued release papers on the basis of the questionnaire will later be free to move unimpeded outside of the camp. Anyone lacking these papers will be promptly arrested and readmitted.”

The Concentration Camp Inmates Questionnaire asked for the prisoners’ personal details and information about their period of imprisonment, as well as specific reasons that might prevent an official release or require further investigation. This could include membership in the Nazi Party or one of its associated organizations, such as the SS.

The decision of the board of review and the names and military ranks of the board members would subsequently be noted on the questionnaire. After the board had convened, an Order For Disposal Of Inmates would be issued. There were three possibilities here: the prisoner could be released, transferred to another prison or sent to a prisoner of war camp. It appears that the US authorities released most of the prisoners. This even applied to prisoners who had been arrested by the Nazis as supposed criminals or homosexuals – legal matters of fact that were still officially considered crimes after the end of the war.

- How common is the document?

Officially, all prisoners in camps liberated by the US Army were supposed to fill out a questionnaire. How many questionnaires were actually filled out is no longer known. A list from 1954 mentions around 15,000 questionnaires from Buchenwald, where the Allies had found around 20,000 prisoners when they liberated the camp. Where questionnaires have been preserved in the Arolsen Archives, they are almost always accompanied by the respective prisoner’s order for disposal. Although there is proof that questionnaires were distributed in Flossenbürg as well, none of these questionnaires have been preserved in the Arolsen Archives.

These detailed questionnaires were only distributed by US authorities. The British and Soviet forces organized the release of prisoners without this document. Furthermore, most of the camps encountered by the Soviet Army during the war had already been largely emptied. The prisoners had been “evacuated” by their German guards and sent west. These death marches, as they are known, meant that there were hardly any prisoners left in the camps for the Soviet liberators to provide for. In Stutthof concentration camp, soldiers found only 300 prisoners who had been left behind. This is why in Poland, for example, instead of distributing a questionnaire, a central office was set up in Toruń to which returning concentration camp prisoners were supposed to report.

- What should be considered when working with the document?

These questionnaires were filled out during a time of great uncertainty and confusion. Dachau prisoner Hans Carls recalled: “The questionnaires were a big headache for a lot of people because they did not want to disclose everything about their lives. They feared that the information they provided could call their release into question. The PSVs [PSV = police preventive custody] in particular were worried about their release” (Hans Carls: Dachau: Dokumente zur Zeitgeschichte II, Cologne 1946, pp. 209f.). For this reason, the information on the questionnaires can sometimes differ from the information in other documents from the person’s imprisonment. Because they were afraid of not being released, prisoners sometimes gave false information, left out important points or formulated things in a way that they hoped would make it more likely for them to be released quickly.

For example, there are two differences between the questionnaire filled out by Josef Jenei and the prisoner registration form that was created for him when he arrived at Buchenwald concentration camp: Jenei changed the details of his nationality and his occupation. On the questionnaire he said he was Romanian instead of Hungarian, and instead of saying he was a painter and draftsman, he said he was a journalist. It is important to bear in mind the origin of each of these documents. In the concentration camps, draftsmen were more in demand than journalists, but after the war there was a greater need for journalists. Comparing multiple questionnaires from a single camp, it is also clear that the answers can be very similar depending on who the translator was. Despite all of these limitations, the questionnaires are a special source of information. For the first time since they had been imprisoned, the liberated prisoners had the opportunity to describe themselves and their experiences in their own words.

If you have any additional information about this document or any other documents described in the e-Guide, we would appreciate it very much if you could send your feedback to eguide@arolsen-archives.org. The document descriptions are updated regularly – and the best way for us to do this is by incorporating the knowledge you share with us.

Variations

Help for documents

About the scan of this document <br> Markings on scan <br> Questions and answers about the document <br> More sample cards <br> Variants of the document