Page of

Page/

- Reference

- Intro

Like all workers in the German Reich, civilian forced laborers were covered by social insurance through their employers. Initially, only Polish civilian workers in agriculture and forestry, and civilian forced laborers from the Soviet Union were exempt from this regulation. From January 1943 and April 1944 respectively, social insurance was mandatory for these laborers too. The social insurance scheme consisted of health, unemployment and invalidity insurance.

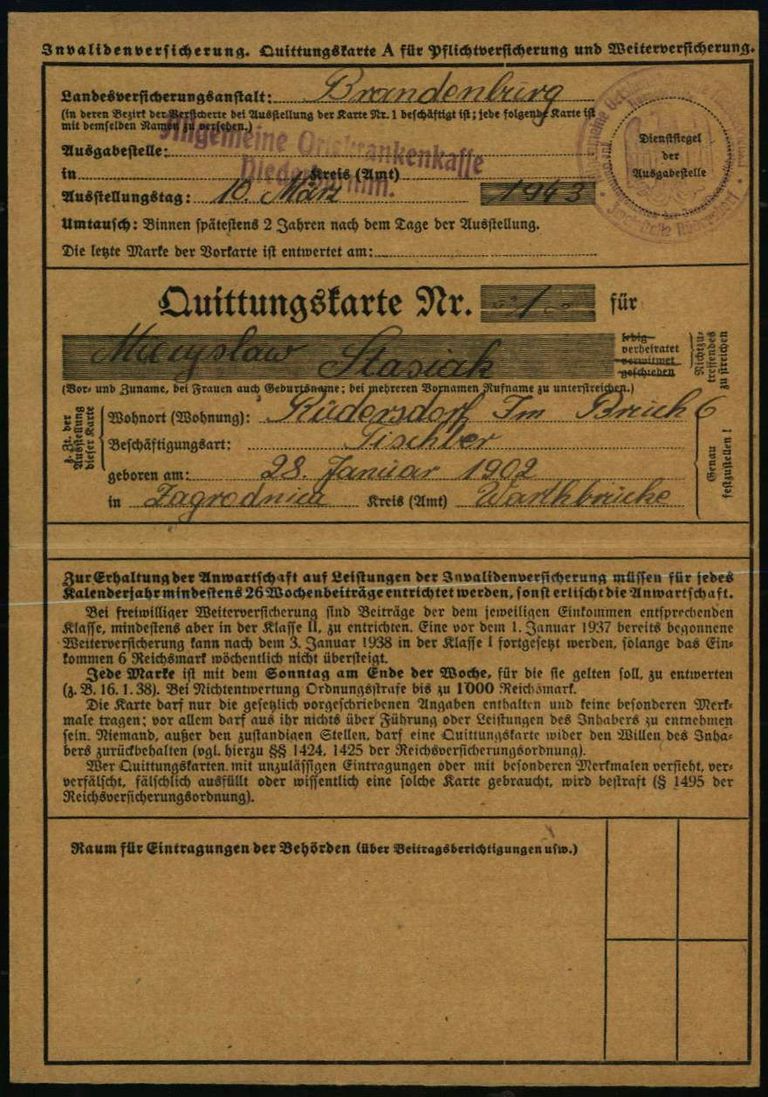

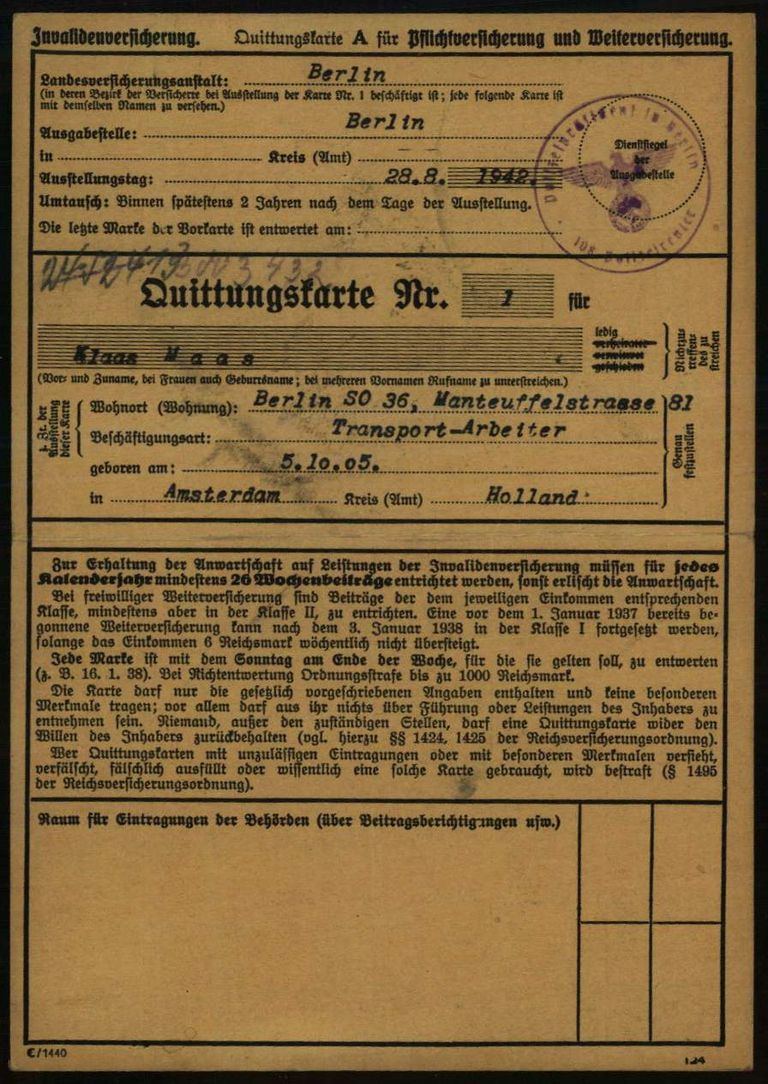

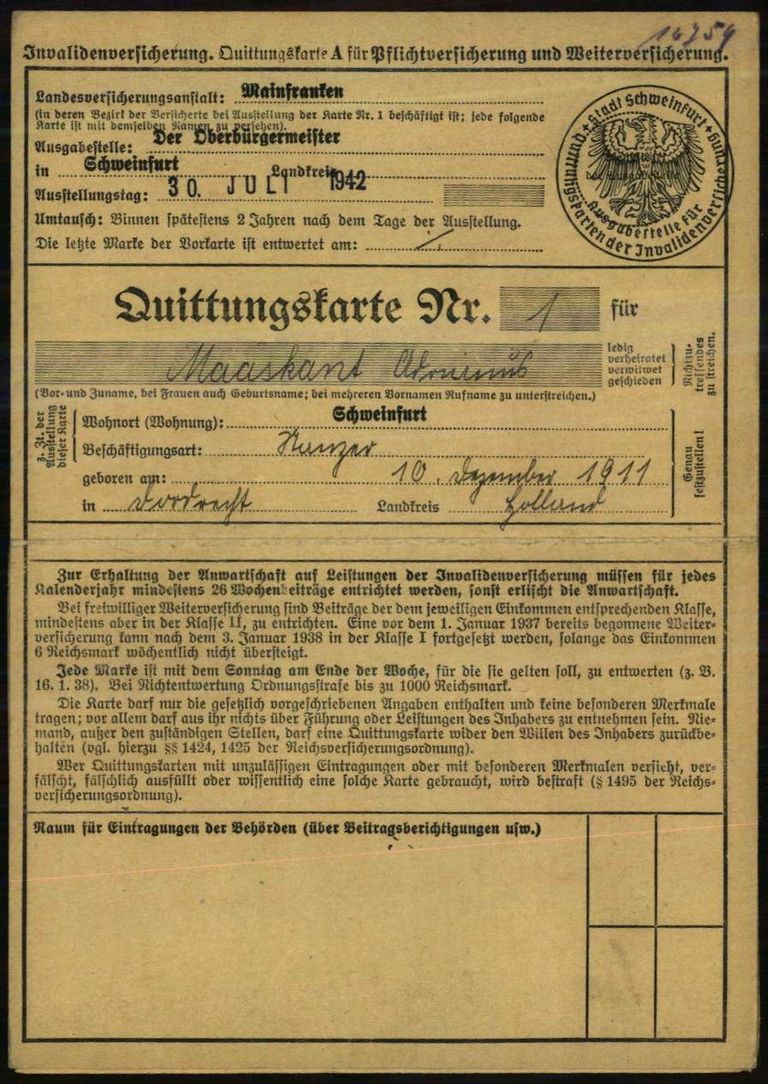

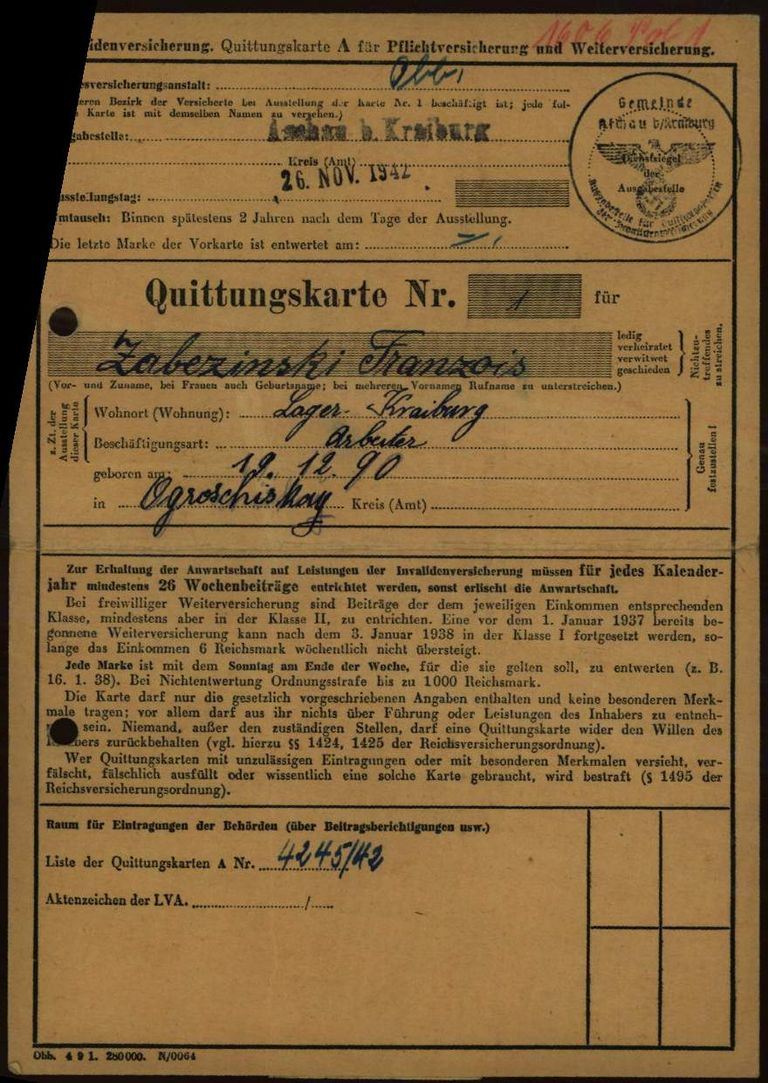

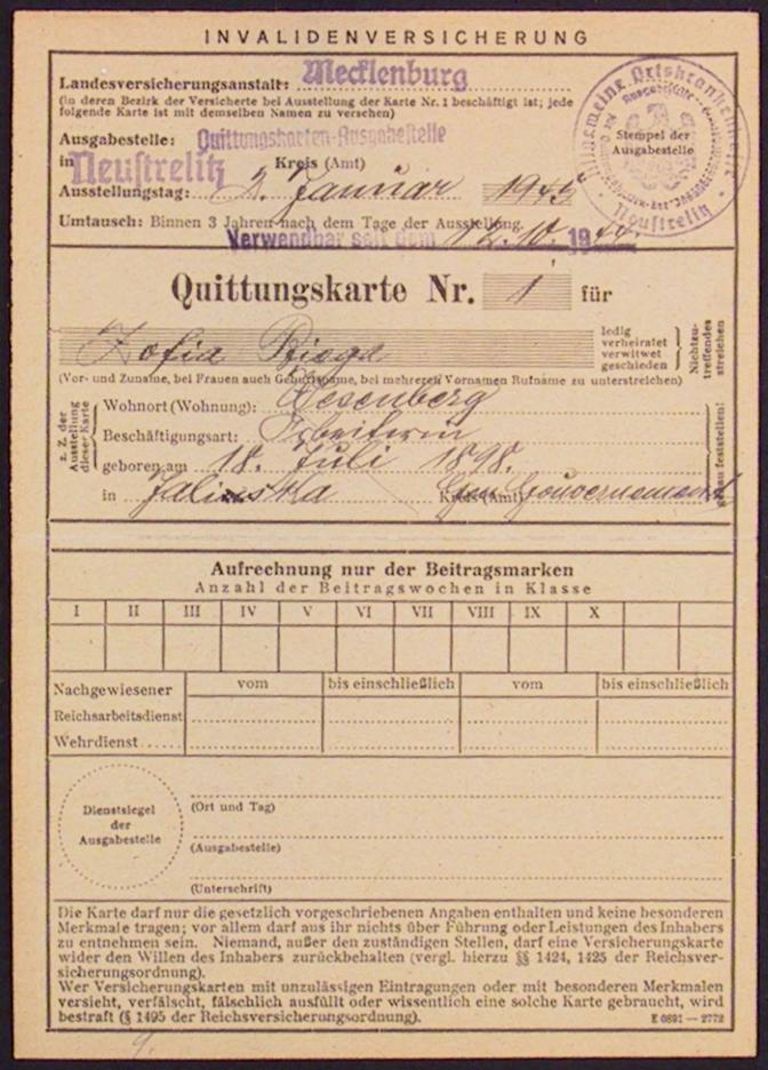

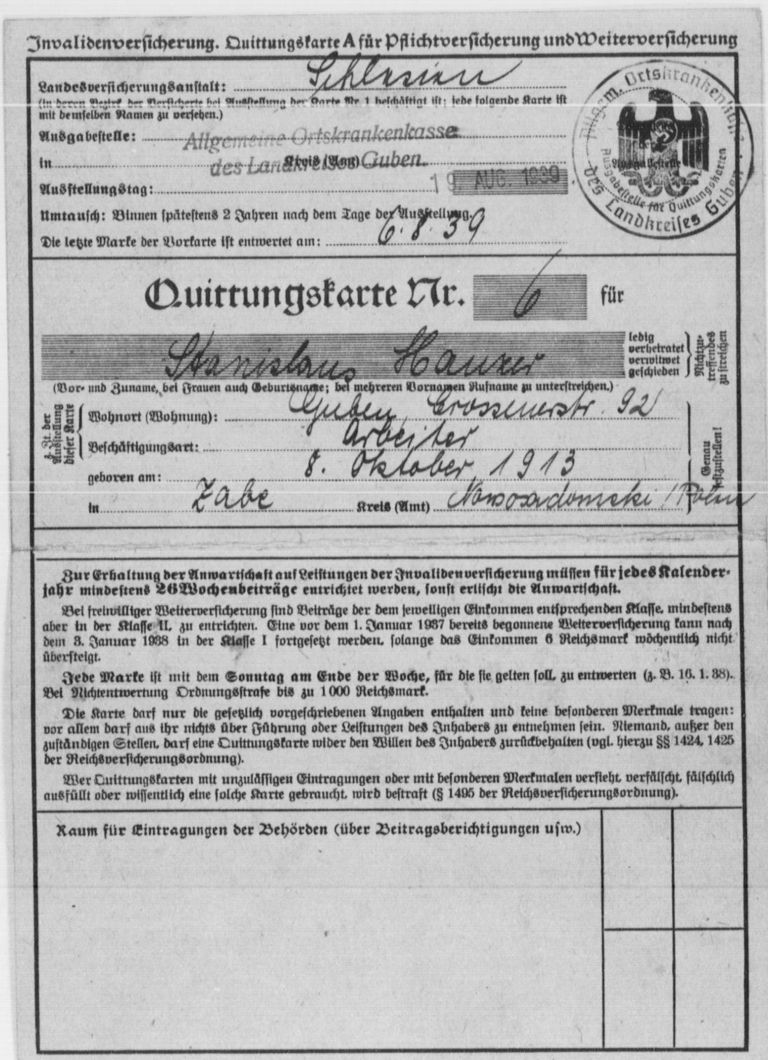

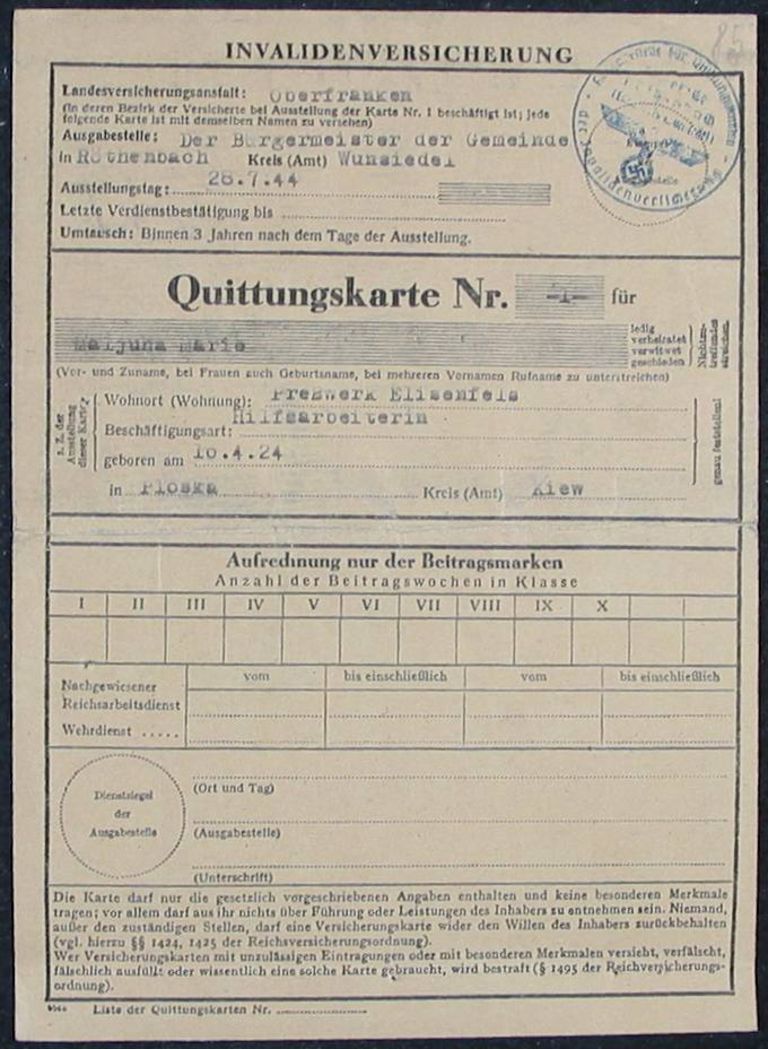

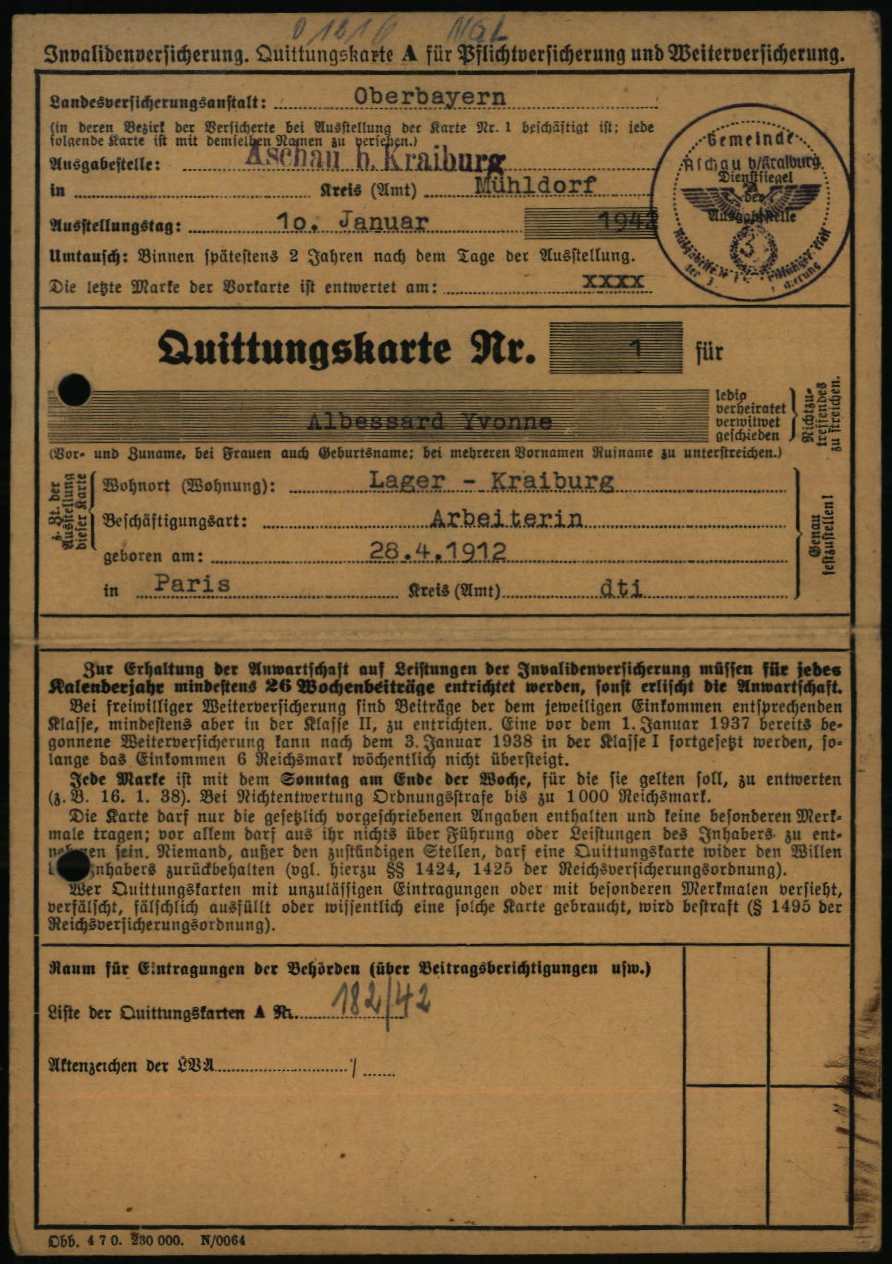

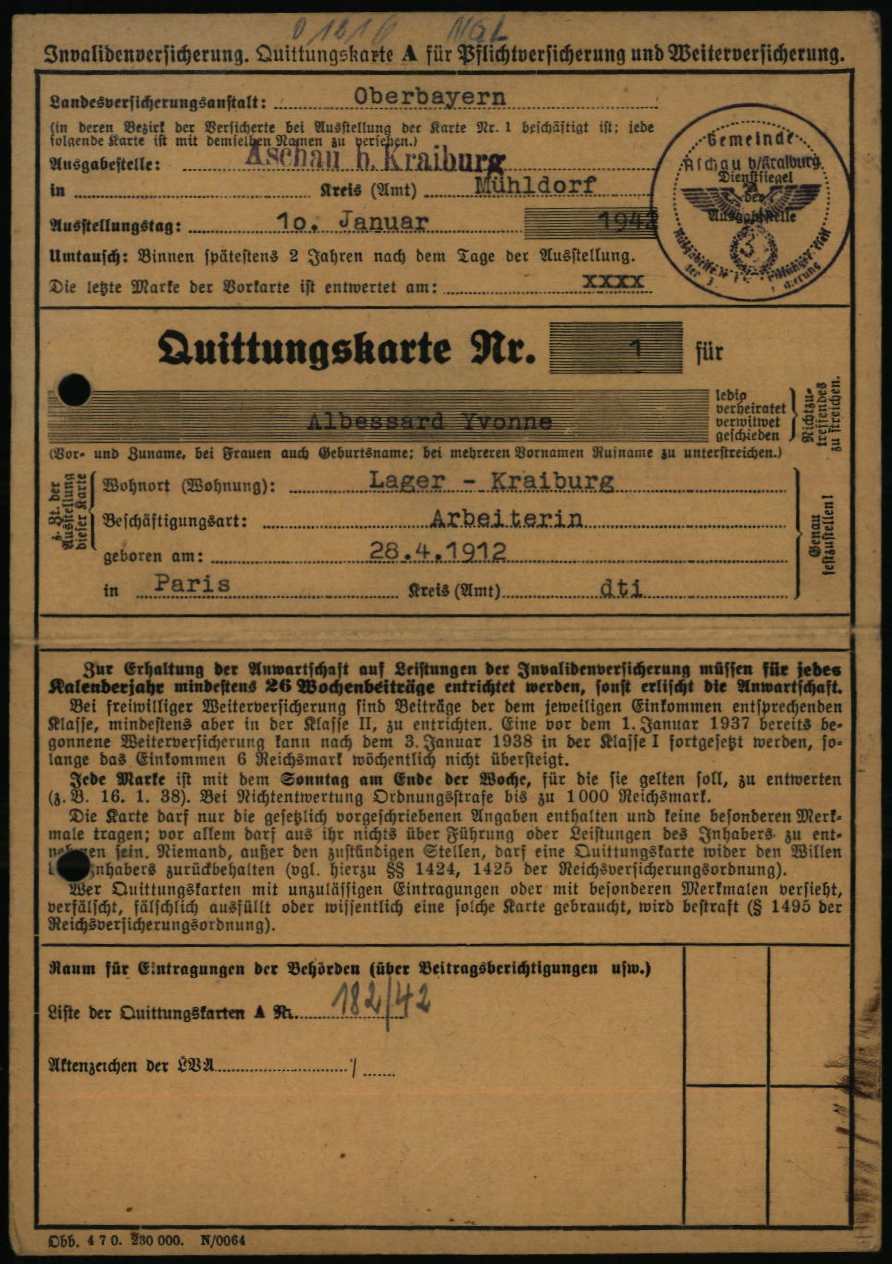

Up until June 1942, civilian forced laborers were required to buy stamps that were pasted into receipt cards (Quittungskarten) for invalidity insurance (Invalidenversicherung, today’s pensions and disability insurance). Receipt cards without stamps were used after this date. With these receipt cards, the civilian forced laborers would have been able to prove that they had made payments for invalidity insurance – but in practice, this was irrelevant as far as they were concerned. Civilian forced laborers rarely received any benefit payments in the event of a claim. Nor did any of the contributions paid later result in any pension rights in Germany. In actual fact, the insurance companies and the Nazi state used the system to make money.

Like all workers in the German Reich, civilian forced laborers were covered by social insurance through their employers. Initially, only Polish civilian workers in agriculture and forestry, and civilian forced laborers from the Soviet Union were exempt from this regulation. From January 1943 and April 1944 respectively, social insurance was mandatory for these laborers too. The social insurance scheme consisted of health, unemployment and invalidity insurance.

Up until June 1942, civilian forced laborers were required to buy stamps that were pasted into receipt cards (Quittungskarten) for invalidity insurance (Invalidenversicherung, today’s pensions and disability insurance). Receipt cards without stamps were used after this date. With these receipt cards, the civilian forced laborers would have been able to prove that they had made payments for invalidity insurance – but in practice, this was irrelevant as far as they were concerned. Civilian forced laborers rarely received any benefit payments in the event of a claim. Nor did any of the contributions paid later result in any pension rights in Germany. In actual fact, the insurance companies and the Nazi state used the system to make money.

Questions and answers

-

Where was the document used and who created it?

Staff at the regional insurance offices (Landesversicherungsanstalten, LVA) and the general local health insurance funds (Allgemeine Ortskrankenkassen, AOK) issued the receipt cards for invalidity insurance. German workers and civilian forced laborers received the same cards. Along with the work book and the income tax card, receipt cards were filed by employers. The staff of the departments responsible regularly pasted the stamps that civilian forced laborers were required to buy as insurance contributions on to the receipt cards. Full cards were sent back to the regional insurance offices. On later receipt cards, employers recorded the contributions that were withheld from civilian forced laborers’ wages instead of using stamps.

- When was the document used?

An invalidity insurance scheme has existed in Germany since the end of the 19th century. In using receipt cards, the Nazis continued a system that had been in place long before they came to power. Insurance contributions were paid by collecting and pasting stamps until June 28, 1942. From July 1942, employers directly withheld part of civilian forced laborers’ wages and paid the respective amount into insurance schemes. The Reich Ministry of Labor introduced new receipt cards without stamps for this purpose, and supplementary sheets that were pasted into existing receipt cards.

- What was the document used for?

Anyone who was employed in the German Reich had to be covered by social insurance. All German and foreign workers paid a portion of their wages for insurance to cover illness, unemployment, and incapacity for work. This applied to civilian forced laborers too; they were required to pay full contributions for invalidity insurance (Invalidenversicherung), the term used for pensions and disability insurance at the time. Initially, only two groups were subject to different rules: Polish civilian laborers in agriculture and forestry were excluded from social insurance until December 31, 1942. Civilian forced laborers from the Soviet Union were not covered by social insurance until April 1944; prior to this, employers paid a lump sum to the insurance providers for the “Ostarbeiter” (“Eastern workers”) who were working for them.

Eventually, all civilian forced laborers were required to pay for invalidity insurance. They were required to pay at least 26 weeks of contributions per year. In order to prove when and how much they had paid, they were also given a receipt card, just like German employees. Up until June 1942, they purchased stamps, which their employers pasted on to the receipt cards. The system changed after this date, and insurance contributions that were deducted directly from wages were recorded using a new receipt card or a supplementary sheet.

After the end of the Second World War, receipt cards were important for clarifying the fates of their holders. As part of the foreigner tracing campaign (Ausländersuchaktion), companies, authorities, insurance companies, and other agencies were required on orders from the Allies to hand over original documents such as receipt cards. These documents were able to provide information about civilian forced laborers in the German Reich.

- How common is the document?

Insurance companies issued at least one receipt card for every civilian laborer who was subject to mandatory insurance contributions. In theory, these were only valid for two years, and so it is possible that there were also follow-up cards for civilian forced laborers. Hence, there must have been millions of receipt cards for civilian forced laborers.

The receipt cards of civilian forced laborers that were currently in use were kept by the employers. The cards remained there after the end of the war, were destroyed, or ended up in archives. Very few of the completed cards that had been sent to the regional insurance offices (LVA) have survived, and even fewer have been passed on to archives. The Arolsen Archives only hold receipt cards relating to a few individuals and from a few employers. As some of the cards have been sorted into the War Time Card File (Collection 2.2.2.1), which contains 4.2 million documents, it is impossible to say how many of them are held in the Arolsen Archives. But in the near future, modern computer technology will find the answer: clustering techniques will make it possible to identify receipt cards, as well as other documents, and to virtually collate cards of the same type. However, the receipt cards of all civilian forced laborers have by no means survived.

- What should be considered when working with the document?

Invalidity insurance – as the pension and disability insurance was called at the time – was designed to support people in times of need. Instead of taking out expensive insurance policies individually, all employees were supposed to pay a small contribution in order to be covered in the event of illness, in their old age, or after accidents, for example. Incapacity for work – which was covered by the invalidity insurance – could result from age – in which case the insurance money would be paid out in the form of a pension – or if a doctor determined that a person was temporarily or permanently unable to work for health reasons. Although all civilian forced laborers paid invalidity insurance contributions from 1944 onwards at the latest, they were not supported to the full extent to which they were entitled. At first, civilian forced laborers who were no longer able to work because they had sustained an injury at work, for example, were sent back to their native countries if they were unable to work for longer than two or three weeks – eight weeks after February 1944. They did not receive the benefit payments to which they would have been entitled under the invalidity insurance scheme. The same was true in the case of pension payments: Civilian forced laborers paid the contributions, but did not receive a German pension. The money that was collected went to the insurance companies or to the Nazi regime without them ever having to pay it out.

If you have any additional information about this document, please send your feedback to eguide@arolsen-archives.org. New findings can always be incorporated into the e-Guide and shared with everyone.

Variations

Help for documents

About the scan of this document <br> Markings on scan <br> Questions and answers about the document <br> More sample cards <br> Variants of the document