Page of

Page/

- Reference

- Intro

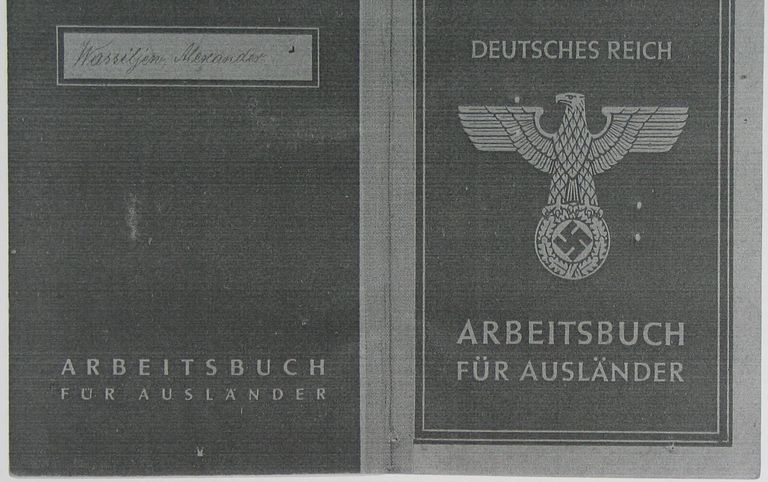

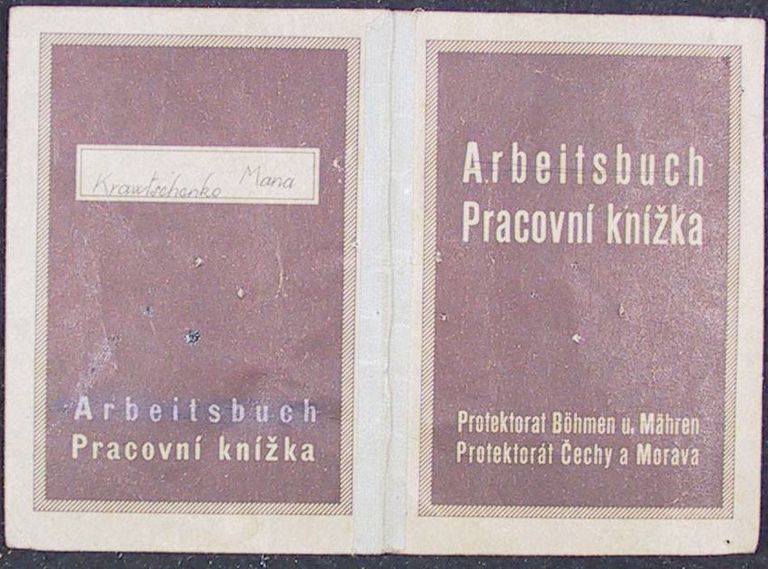

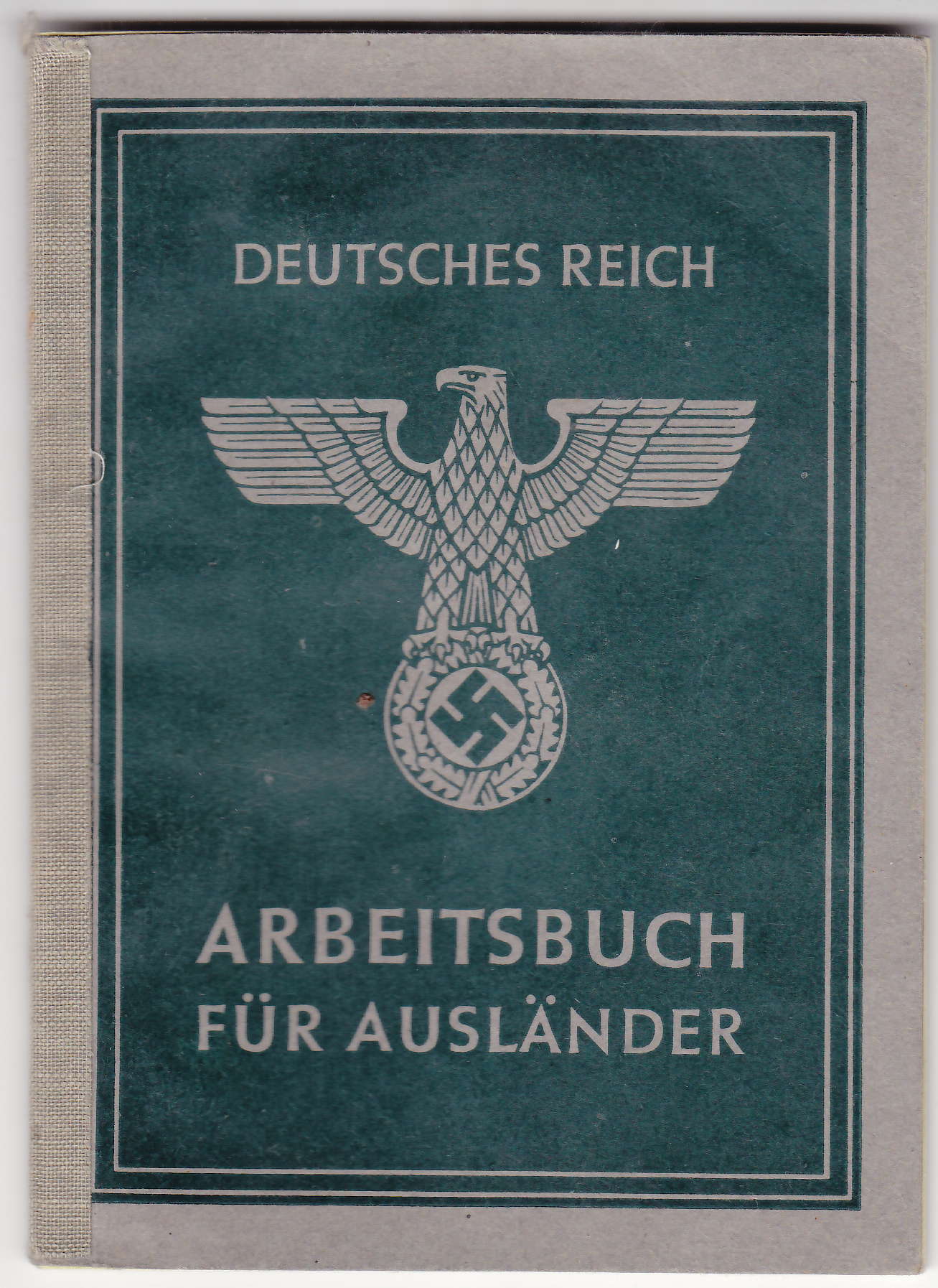

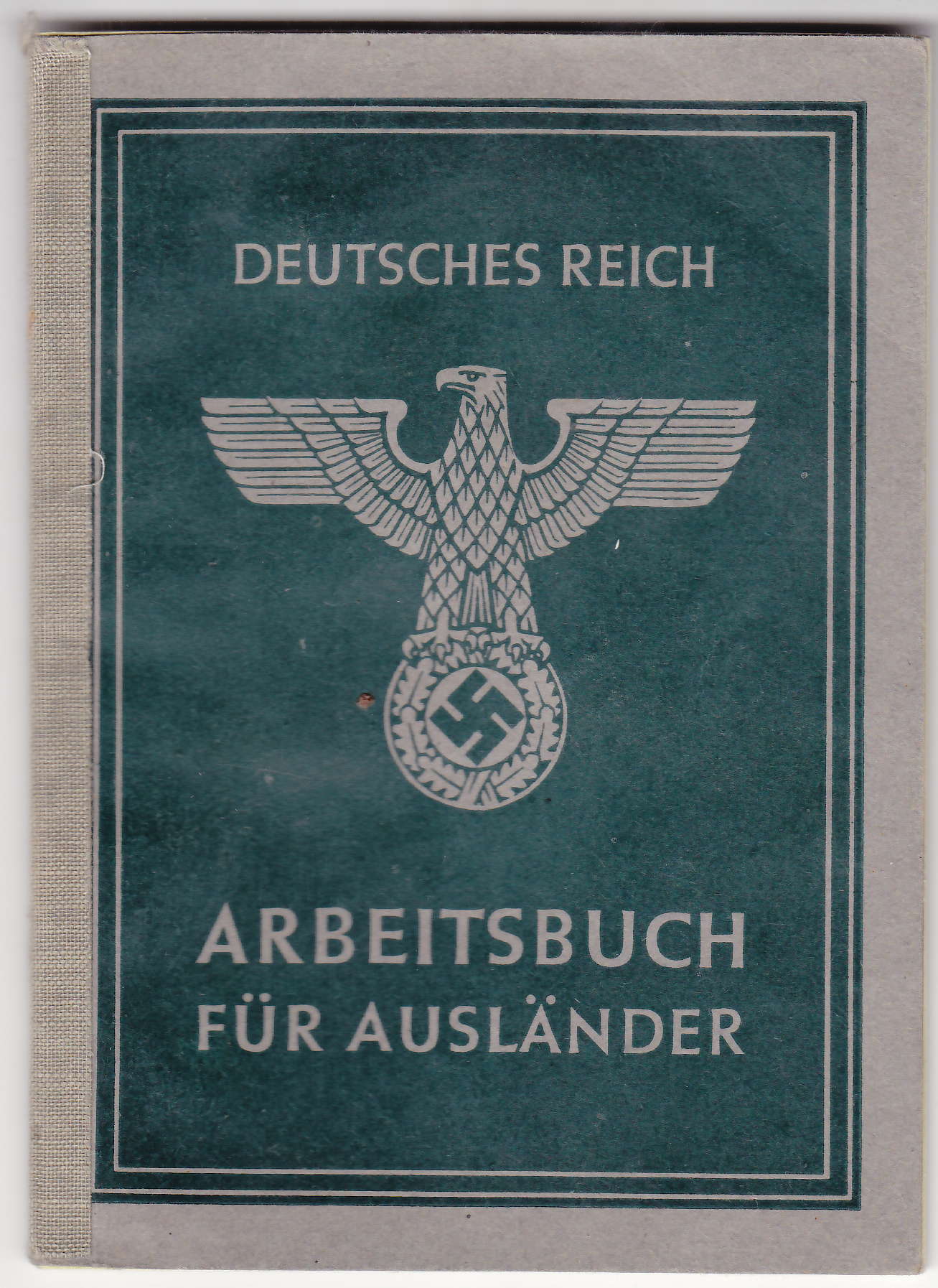

Work books (Arbeitsbücher) were documents that were found everywhere in the German Reich from the mid-1930s onwards. All German workers were required to hand one in at their place of work. No one could be employed without a work book. Civilian forced laborers were also given a work book. Initially, this was the same as the work book given to Germans, but from May 1943 onwards, there was a separate work book for foreigners (Arbeitsbuch für Ausländer). Work books and the corresponding work book cards were used to manage and coordinate labor deployment (Arbeitseinsatz). The Nazis used this term to describe the state regulation of the labor market.

Work books (Arbeitsbücher) were documents that were found everywhere in the German Reich from the mid-1930s onwards. All German workers were required to hand one in at their place of work. No one could be employed without a work book. Civilian forced laborers were also given a work book. Initially, this was the same as the work book given to Germans, but from May 1943 onwards, there was a separate work book for foreigners (Arbeitsbuch für Ausländer). Work books and the corresponding work book cards were used to manage and coordinate labor deployment (Arbeitseinsatz). The Nazis used this term to describe the state regulation of the labor market.

Questions and answers

-

Where was the document used and who created it?

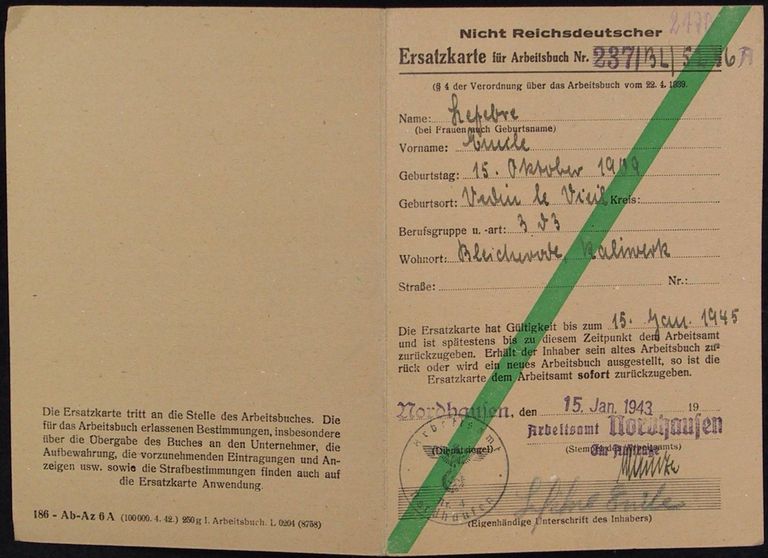

Staff at the local employment offices issued work books together with work book cards. Employers applied for work books and entered details about the respective job. They kept the work books of civilian forced laborers for as long as the laborers worked for them. If civilian forced laborers were assigned a new job, they were given back their work book to hand in to their new employer. Before they were given back their work books for this change, their employers sent their work books to the relevant employment office. Staff updated the work book cards held there accordingly. Sometimes, the employment office then sent work books directly to the new employers. The work books of civilian forced laborers who left the German Reich because they were sent back to their native countries due to illness, for example, had to be returned to the relevant employment office.

- When was the document used?

From as early as May 1935, German workers were increasingly required to keep a work book. From May 1941, all foreign workers were also required to keep a work book. Consequently, civilian forced laborers were given a work book as well. The General Plenipotentiary for Labor Deployment (GBA), Fritz Sauckel, introduced separate work books for foreigners in the “Decree on Work Books for Foreign Workers” of May 1, 1943. These were used until the end of the war.

- What was the document used for?

Controlling the labor market was very important for the Nazi leadership. Hence, throughout the 1930s they introduced more and more rules, firstly for German blue and white-collar workers. They, for example, were only allowed to change jobs if they had official permission from the employment offices. Furthermore, they could be transferred to other places of work without being asked, if the employment offices considered that they were needed more urgently elsewhere. In order to exercise better control over the labor market, the Reich Ministry of Labor introduced a work book for more and more German workers from 1935 onwards. The category of people was gradually expanded until the entire German working population was required to have a work book. In addition to personal details and information about professional skills, work books essentially contained entries for each of the person’s jobs.

Civilian forced laborers were also given a work book. Initially, the same work book that was given to German workers was used, but from May 1943 onwards, there was a separate work book for foreigners (Arbeitsbuch für Ausländer). The way it worked was the same: Employers applied for a work book for all civilian forced laborers employed by them from the relevant employment office. They were required to provide the personal details of the civilian forced laborers in their application, which the employment office staff then transferred to the work book. Once this was done, they sent the work books to the companies, municipal or church offices, farmers or private households, where the civilian forced laborers signed them. Employment office staff also issued work books directly in the companies or in the communal accommodation where the civilian forced laborers were working or living so that the process could be completed more quickly.

Employers kept the work books of all their employees so that they could not change jobs unnoticed. The rule was that only those who could hand in a work book could be hired. To ensure that the relevant employment office was always kept up to date, employers were required to report any changes related to their employees.

The forced labor of concentration camp prisoners and prisoners of war was not recorded in work books. The obligation to keep a work book only applied to civilian forced laborers. The work books of imprisoned civilian forced laborers were however sent back and forth between employers, labor re-education camps, prisons, Gestapo offices, and concentration camps. The personal effects cards used in the concentration camps included a separate field for work books. Employment offices wrote letters to the concentration camp administrations trying to establish the whereabouts of work books.

- How common is the document?

In theory, there was a work book for all civilian forced laborers. Several million of these were in circulation with the introduction of the work book for foreigners (Arbeitsbuch für Ausländer) alone. Following liberation, many work books remained with employers, or were deliberately destroyed in order to cover up traces of forced labor. Some liberated civilian laborers took their work books with them when they went home to their native countries.

Work books were only gradually sent to the International Tracing Service (ITS), the predecessor institution of the Arolsen Archives. This happened mostly in connection with the foreigner tracing campaign (Ausländersuchaktion) after the war. On the orders of the Allies, German companies and employment offices at that time also sent in originals of work books in some cases. However, most work books only came to the ITS as scanned documents or microfilms from company, city, and local authority archives from the 1980s onwards. Exactly how many work books are preserved in the Arolsen Archives today is not known. But in the near future, modern computer technology will find the answer: clustering techniques will make it possible to identify work books, as well as other documents, and to virtually collate documents of the same type. However, the work books of all civilian forced laborers have by no means survived.

- What should be considered when working with the document?

The work book contains 40 individual pages. Most of the pages were set aside for changes of job, which did not happen all that often, so that these identical pages were almost always left blank. When staff at the International Tracing Service (ITS), the predecessor institution of the Arolsen Archives, scanned the documents for the archive, they usually omitted these blank pages. Consequently, often only the first few pages of a work book can be found in the Arolsen Archives. These list the most important personal details of the civilian forced laborer, and details of their employers.

If you have any additional information about this document, please send your feedback to eguide@arolsen-archives.org. The document descriptions in the e-Guide are updated regularly – and the best way for us to do this is by incorporating the knowledge you share with us.

Variations

Help for documents

About the scan of this document <br> Markings on scan <br> Questions and answers about the document <br> More sample cards <br> Variants of the document