Page of

Page/

- Reference

- Intro

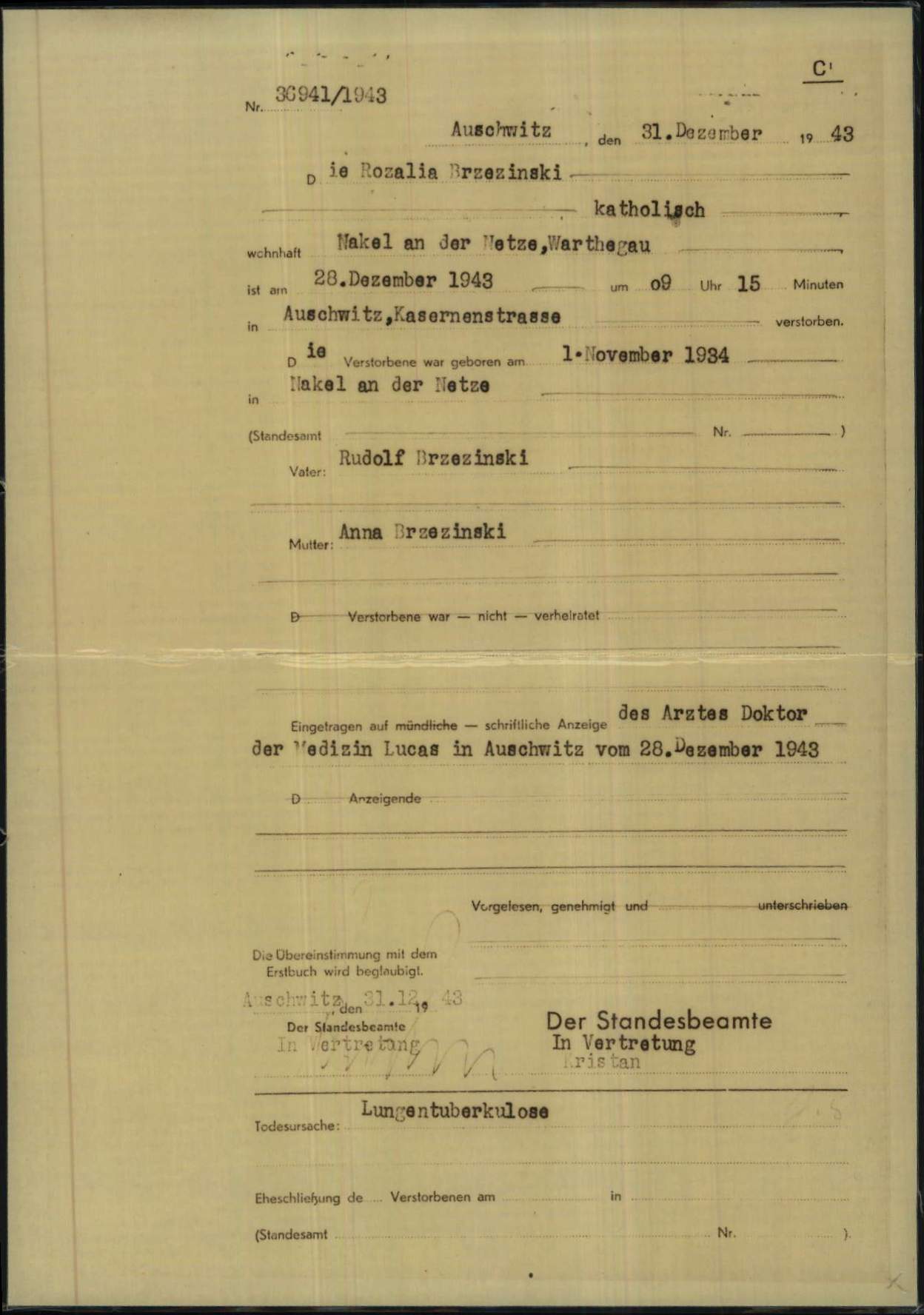

This document is officially known as a death register entry or death book entry. It is a form that was officially filled out not only for concentration camp prisoners but others as well. As a formal act that still applies today, deceased persons must be registered at a German registry office. Deceased concentration camp prisoners were therefore also supposed to be listed in a death register – though there were major differences here depending on the prisoners’ nationality and whether they were considered Jews. The form was basically identical in all camp and civil registry offices. This is why the entries for Spanish, German and Polish deceased prisoners from different concentration camps are similar. They differ only in their typeface and the handwriting of the respective registrars.

This document is officially known as a death register entry or death book entry. It is a form that was officially filled out not only for concentration camp prisoners but others as well. As a formal act that still applies today, deceased persons must be registered at a German registry office. Deceased concentration camp prisoners were therefore also supposed to be listed in a death register – though there were major differences here depending on the prisoners’ nationality and whether they were considered Jews. The form was basically identical in all camp and civil registry offices. This is why the entries for Spanish, German and Polish deceased prisoners from different concentration camps are similar. They differ only in their typeface and the handwriting of the respective registrars.

Questions and answers

-

Where was the document used and who created it?

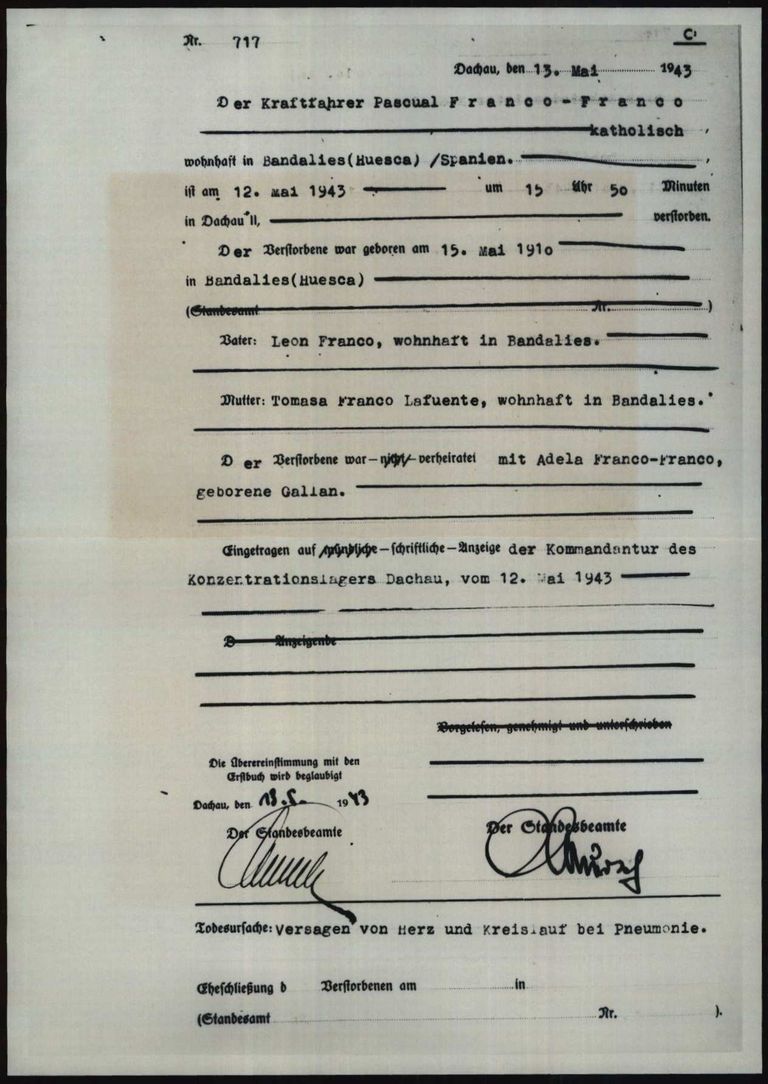

The deaths of concentration camp prisoners were precisely managed like all other aspects of their camp existence. The Political Department of the concentration camp was responsible for entering the names of the deceased in the death books of the nearest civil registry offices (Standesämter). The civil registry offices could be informed of a prisoner’s death in writing, as was the case in Auschwitz – or, as in the Dachau and Hinzert concentration camps, an SS officer could personally visit the civil registry office to report a prisoner’s time and date of death, as well as the supposed cause of death.

During World War II, the number of deaths in the camps rose rapidly. A quote from a 1949 indictment read out against members of the SS who had been assigned to Hersbruck, a sub-camp of Flossenbürg concentration camp, illustrates: “Concerned that the continually growing number of deaths might become known to further circles via the civil registry office, the SS leadership set up their own registry office in the camp which could also inform family members left behind.” (1.1.8.0/82109760/ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives) From the early 1940s the main camps established their own camp registry offices (Lagerstandesämter), which were supervised by the local civil registry offices. Buchenwald had its own registry office as early as April 1939, however. These camp registry offices had names such as Dachau II (established in June 1941) and Flossenbürg II (which began work in October 1942). Unlike the offices in other camps, the camp registry office in Neuengamme was referred to as Neuengamme A. Bergen-Belsen was another exception; since there was no civil registry office in the neighboring village of Bergen, the camp registry office was run under the name of Bergen-Belsen. In September 1943 there were a total of 16 main camps with their own registry offices. The deaths of prisoners in the sub-camps and external labor details were sometimes registered in the local civil registry offices and sometimes in the camp registry offices. Despite the rule that stated all reports should go through the camp registry offices, there was no standardized procedure here.

Even shortly before the end of the war, some prisoners who died on death marches or transports would be registered in the civil registry offices of the localities through which the prisoners passed. This was an exception, however, because most of the prisoners who died in the final weeks and months of the war were not reported to a registry office. In Neuengamme concentration camp, registration ended on March 15, 1945, over a month before the camp was dissolved.

- When was the document used?

Reporting a death was a bureaucratic act, and it was required for all German and (with some major exceptions) foreign prisoners throughout the existence of the concentration camps. The civil and later camp registry offices primarily registered deceased German and Western European prisoners between 1933 and 1945. The deaths of Jewish prisoners and those from Central and Eastern Europe were increasingly not officially registered.

Family members were informed that a death certificate could be issued at their own expense if needed. Since these certificates were sent directly to the relatives of the deceased, they were not among the documents confiscated by the Allies and given to the ITS after the camps had been liberated.

- What was the document used for?

After the camp doctor had officially confirmed a prisoner’s death, there were numerous steps to be taken by the different camp administrative departments. The Political Department, the block leader room, the prisoner registry office and the personal effects storage room were all notified. The prisoner would be recorded as deceased in the card files of the registry office and the Political Department, and the report leader would list the deceased prisoner in the camp statistics in the Abgang (“departure”) section.

For the official registration of a death, the names and personal details of the deceased were entered in two death books (Sterbebücher) in the civil or camp registry offices. One book would remain in the civil registry office, and the second would be sent to the administrative district or another higher-level authority. The two books were kept separate from one another so that if one was damaged or destroyed, the other would still be available. This is why there are now first and second books in the Arolsen Archives.

In the early years, the camp commandant would notify the family members of a death by telegram. From May 1942, this responsibility was taken over by the authority that had admitted the prisoner to the concentration camp. Additionally, the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA) and Office Group D of the SS Chief Economic and Administration Office (WVHA) – the highest administrative authorities – were informed of all deaths in the camps by telex and express letter. Finally, the personal effects storage room would handle the deceased prisoner’s possessions, which would either be confiscated and declared state property or be returned to the prisoner’s family.

This process depended heavily on the nationality of the deceased, however. The registry officer for Dachau II, Chief Squad Leader Mursch, said during questioning in 1946 that the death of Russian prisoners was “fundamentally never certified” (1.1.6.0/ 82095293/ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives). After the war, an investigation by the UNRRA District Records Officer revealed that in the documents of the Buchenwald camp registry office, more than 50 percent of the deceased Polish, Russian and Yugoslavian concentration camp prisoners had been registered incorrectly or not at all.

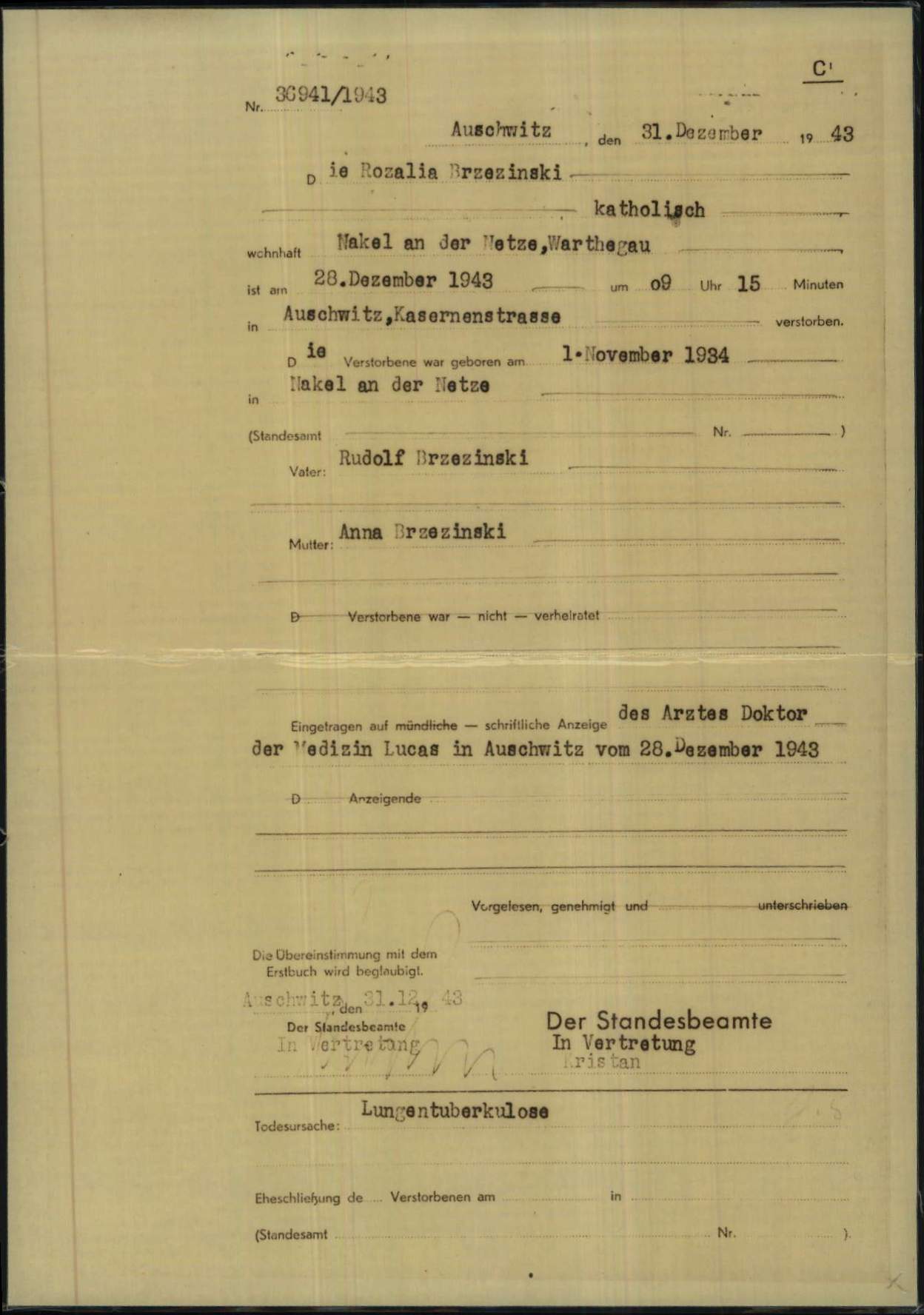

A deceased prisoner’s nationality determined both whether the prisoner would be recorded in a death book and how his or her relatives would be dealt with. The relatives of Polish and Jewish prisoners, for example, were not offered the option of receiving the prisoner’s ashes in an urn, and a death certificate was not always issued either. From November 1939, there was no longer any obligation to notify the relatives of deceased Polish or Jewish prisoners. By December 1942 at the latest, the relatives of Republican Spaniards, most of whom had been arrested in French exile after the Spanish Civil War (known as Rotspanier, or “Red Spaniards”), were only notified of the prisoner’s death if either the relatives themselves or the Red Cross actively inquired about the person.

The death certificates issued by civil and camp registry offices on the basis of their death books would be sent to the relatives of the deceased prisoners. Before May 1945, the relatives of German prisoners needed these certificates in order to collect life insurance, clarify inheritance questions, request support from Nazi aid organizations or remarry. After the war, death certificates were important for clarifying compensation questions and applying for welfare services.

However, death book entries do not exist for anywhere near all of the prisoners who died in the concentration camps. There are no official death records at all for the many people who were murdered immediately after arriving at an extermination camp, or for most of the concentration camp prisoners who died on death marches. Even if a person’s death was registered, this does not mean that the documents still exist today. The death books often burned up in the registry offices of larger cities that were bombed, and the Germans deliberately destroyed many of them shortly before the end of the war in order to cover up their crimes.

- How common is the document?

There are few of these original documents in the Arolsen Archives. By far not all of the prisoners who died in a concentration camp were recorded in a death book, many of the documents were destroyed, and not all the certificates that were saved wound up at the ITS. Most of the death certificates and death book entries in the Arolsen Archives are copies.

- What should be considered when working with the document?

In their death certificates and death book entries, the Nazis tried to present a toned-down image of death in the concentration camps. They wanted to conceal deaths that had occurred as a result of the catastrophic living conditions and deliberate murder. For this reason, false diagnoses are sometimes written on the death certificates. The same illnesses appear again and again because the camp doctors did not examine every single deceased prisoner, but instead gave a general cause of death, which would then be entered on the death certificate or in the death book. Natural causes of death were also recorded for prisoners who had been murdered and those who died as a result of human medical experiments.

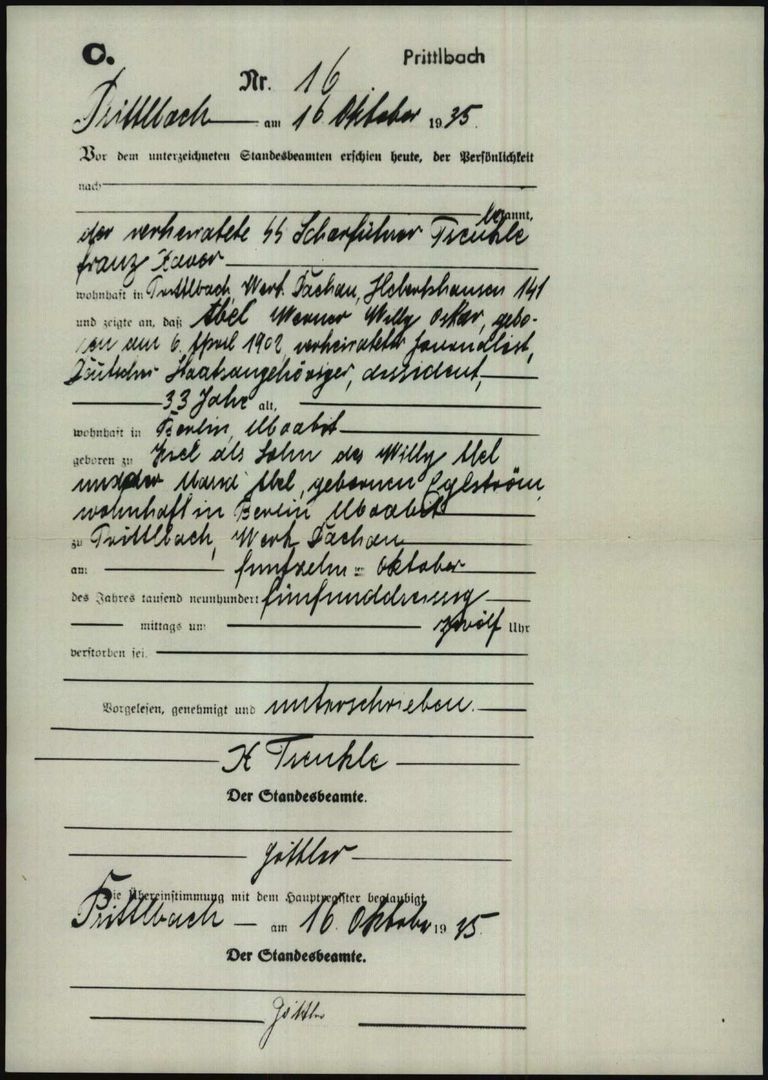

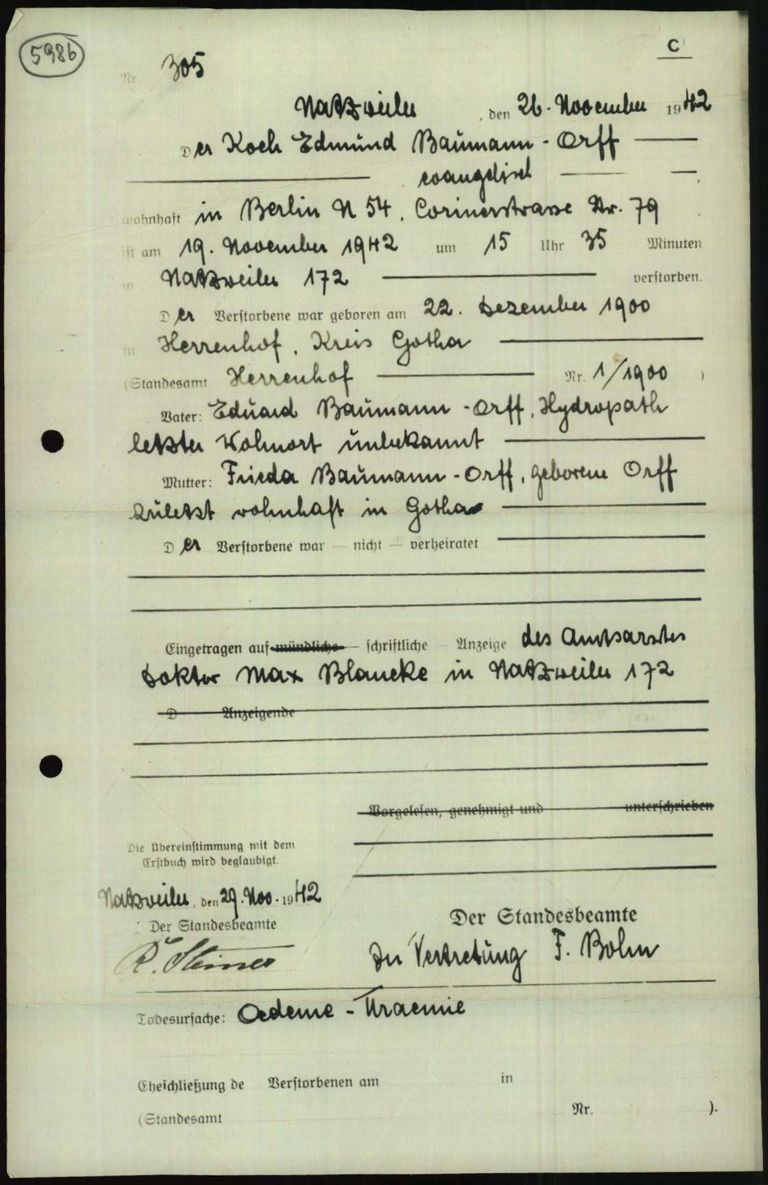

Furthermore, the death book entries do not even mention the concentration camps. When prisoner deaths were recorded in Auschwitz, for example, the entries mention only Auschwitz, Kasernenstrasse (“Auschwitz, Barracks Street”) as the place of death. Certificates for prisoners who died in Natzweiler concentration camp mention Natzweiler 172 as the place of death, and a certificate for a prisoner from Dachau mentions Prittlbach, Werk Dachau (“Prittlbach, Dachau factory”). This can be considered part of the Nazis’ attempt at concealment, but it also follows a regulation that exists to this day for hospitals and prisons: if someone dies in one of these institutions, the institution itself is not named, only the town and, in some cases, the street.

After the war, death books were still updated and death certificates were still issued in local registry offices – sometimes even for unknown deceased prisoners. Since official death certificates are important for legal reasons alone, and the German Civil Status Act (Paragraph 38) stipulates the registration of deaths in concentration camps, a central Special Registry Office (Sonderstandesamt) was established in Arolsen on September 1, 1949. Ever since then, the Special Registry Office has been the only authority allowed to certify deaths in former German concentration camps. To this day, death certificates are issued and corrections are made when the death of a concentration camp prisoner has been confirmed based on the archival material of the Arolsen Archives or on research in other registry offices and memorials.

If you have any additional information about this document or any other documents described in the e-Guide, we would appreciate it very much if you could send your feedback to eguide@arolsen-archives.org. The document descriptions are updated regularly – and the best way for us to do this is by incorporating the knowledge you share with us.

Help for documents

About the scan of this document <br> Markings on scan <br> Questions and answers about the document <br> More sample cards <br> Variants of the document