Page of

Page/

- Reference

- Intro

Employers were required to register civilian forced laborers who worked for them with a public health insurance fund. In return, forced laborers were required to pay part of their wages as a contribution. In theory, they were insured in the event of illness. In reality, however, the medical treatment varied widely depending on the nationality of the civilian forced laborers. In most cases, the services provided fell far short of those available to Germans.

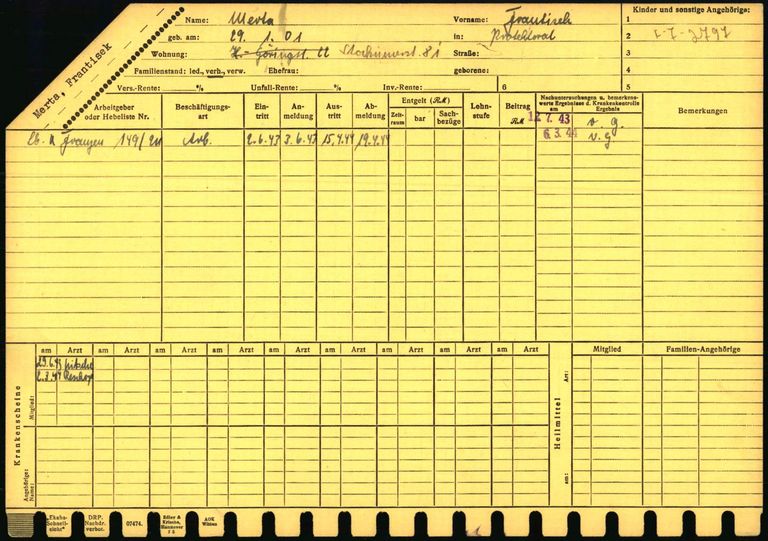

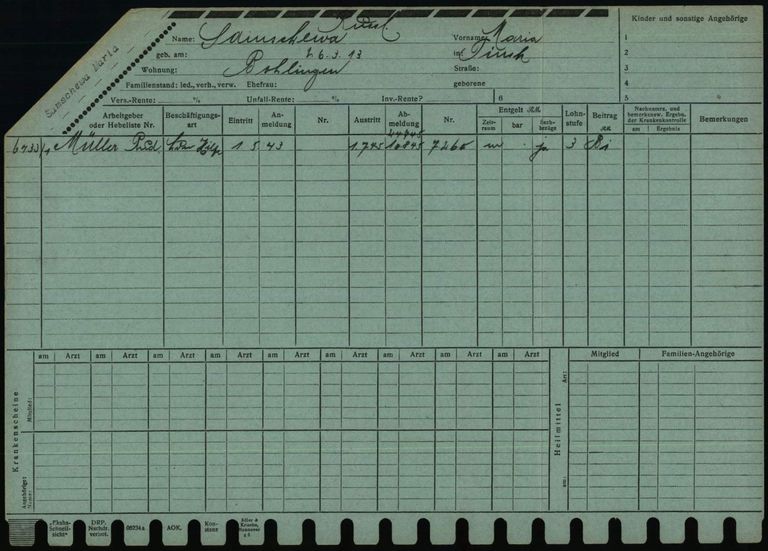

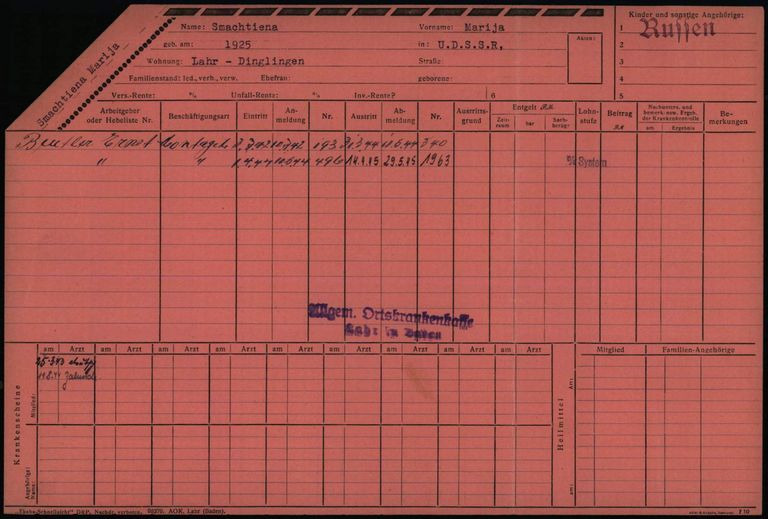

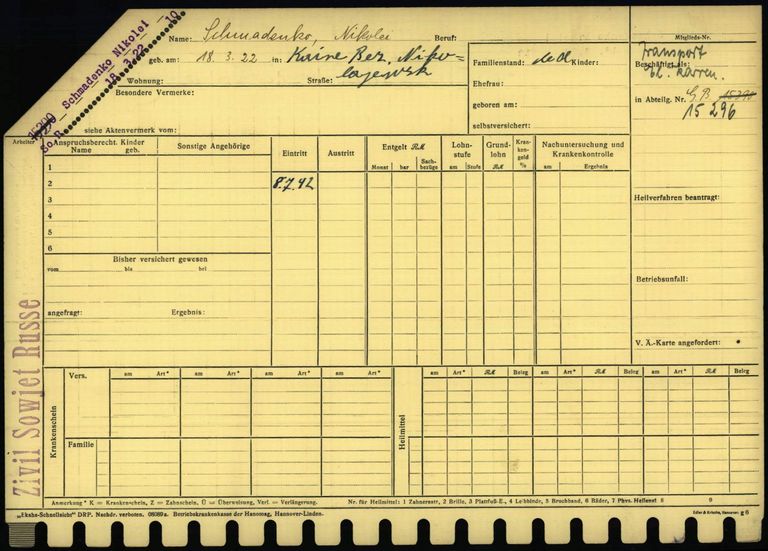

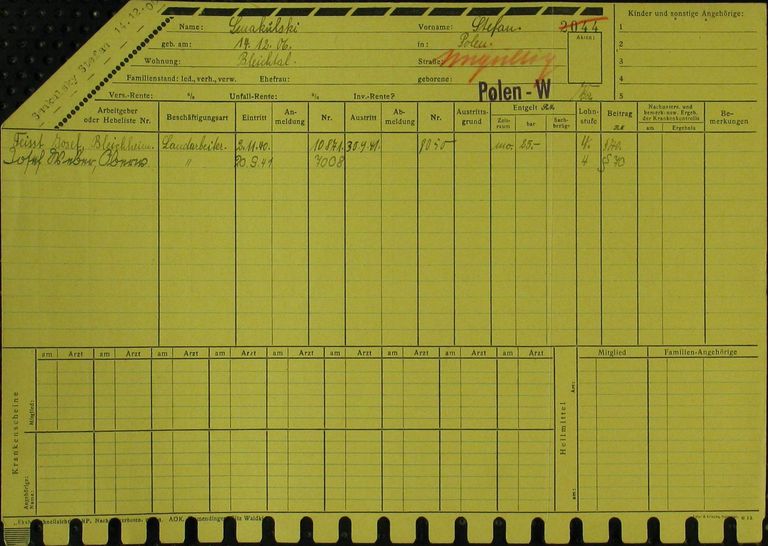

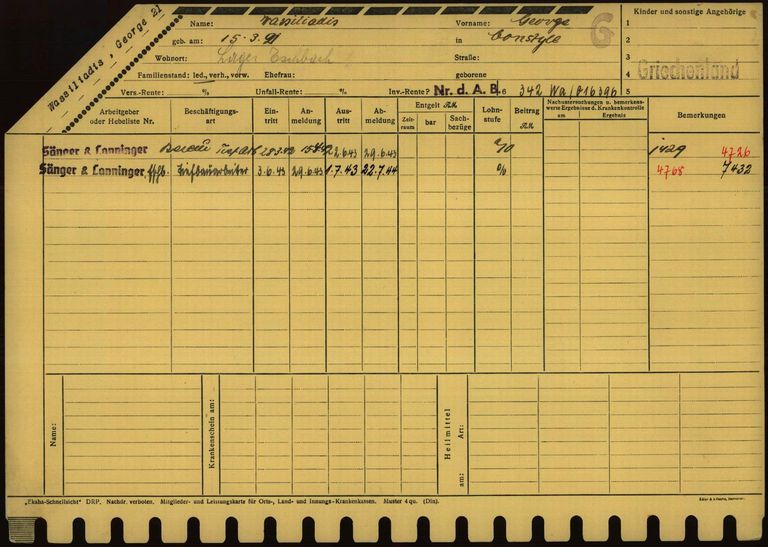

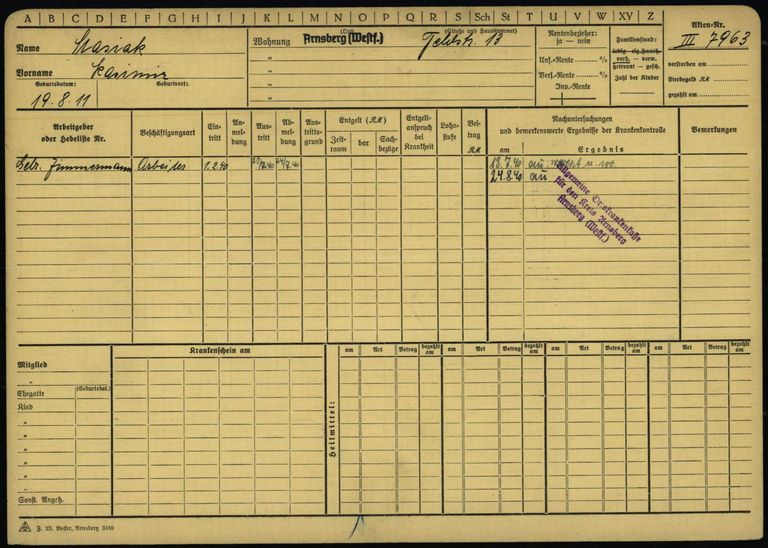

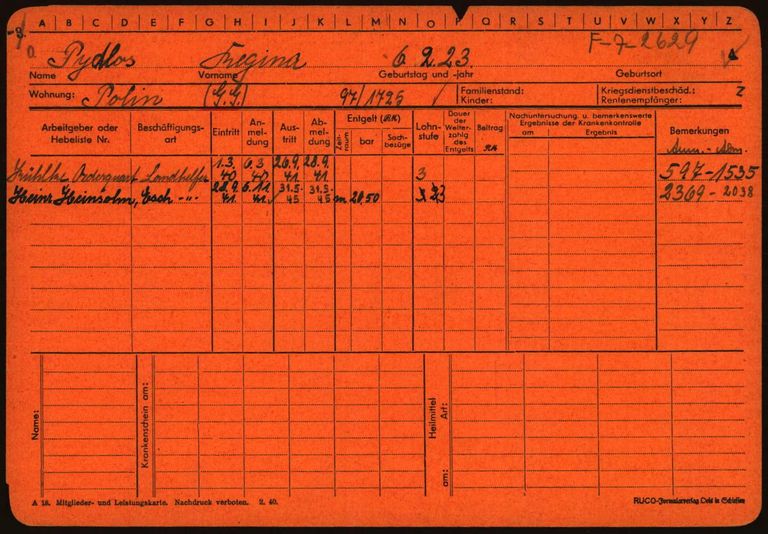

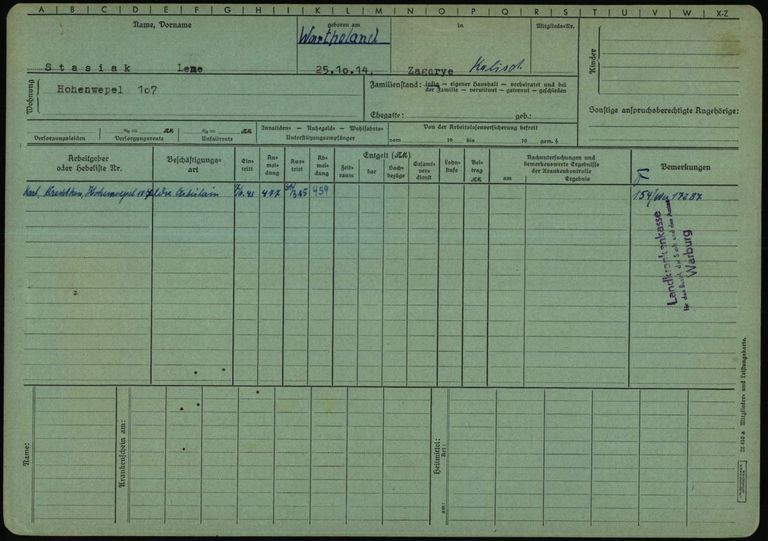

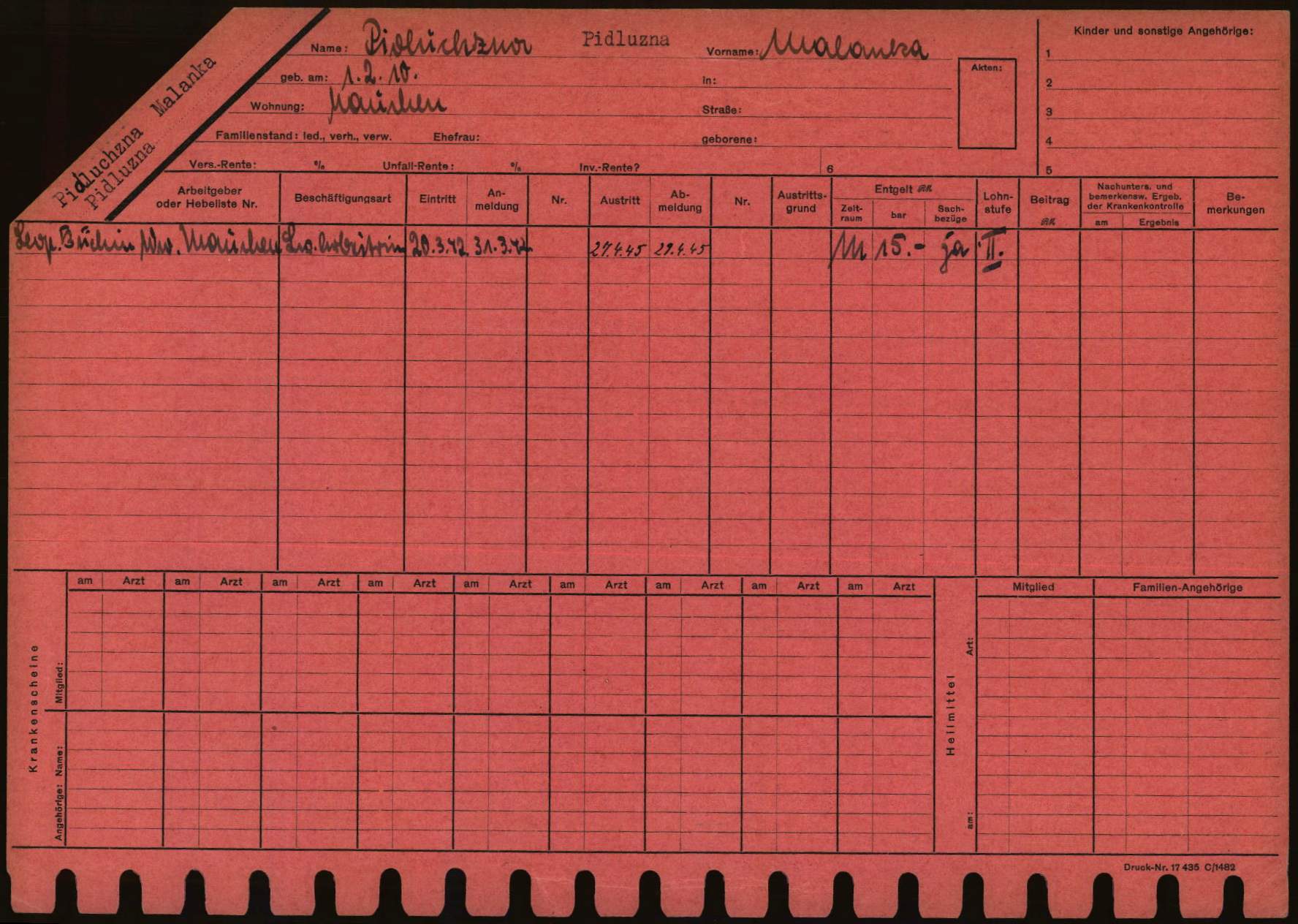

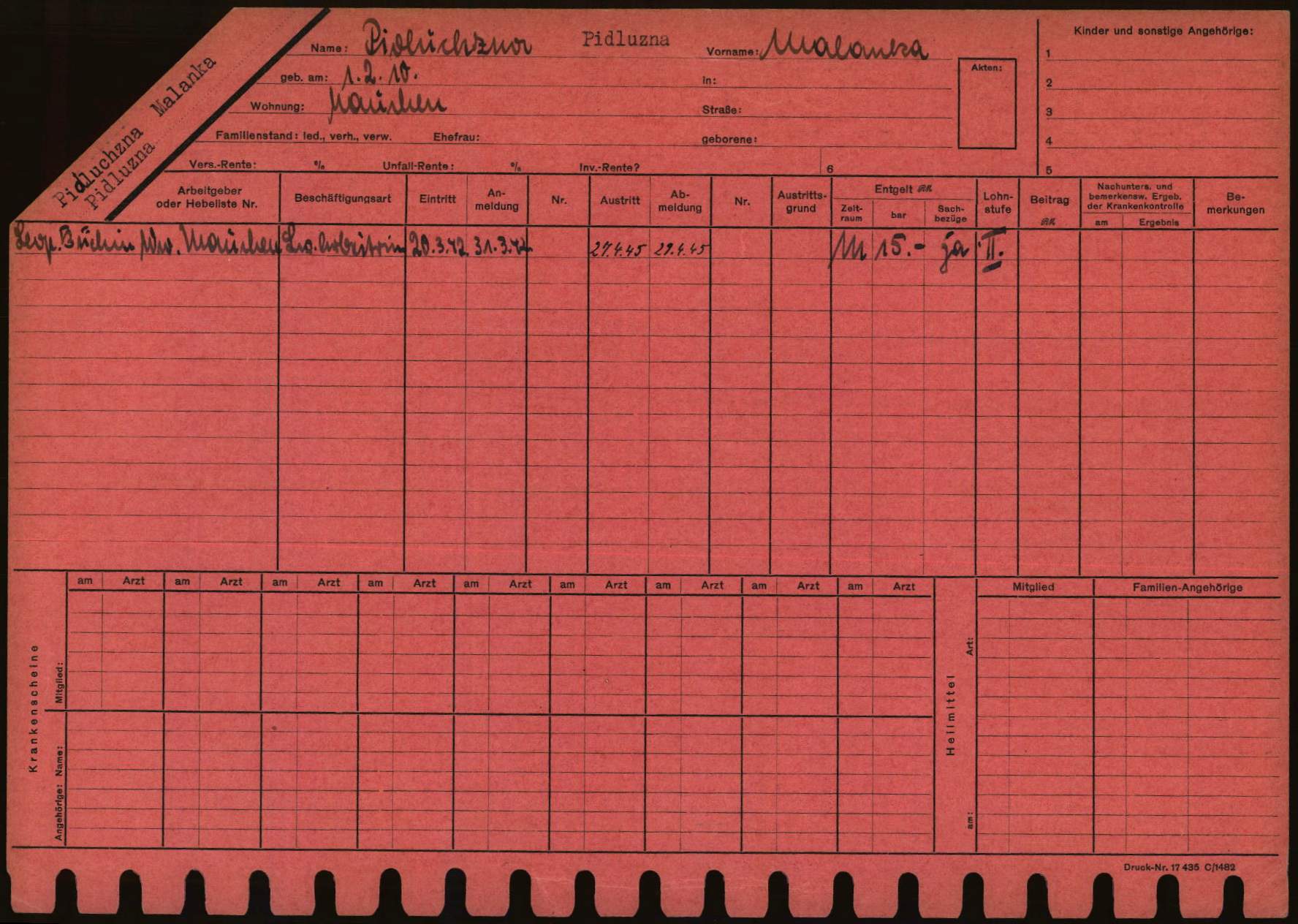

The public health insurance funds issued a member and benefit card (Mitglieder- und Leistungskarte) for each person who was insured with them. The different public health insurance funds used different preprinted cards, which vary in terms of color and layout. Although they look different at first glance, they always contain the same information in virtually every case.

Employers were required to register civilian forced laborers who worked for them with a public health insurance fund. In return, forced laborers were required to pay part of their wages as a contribution. In theory, they were insured in the event of illness. In reality, however, the medical treatment varied widely depending on the nationality of the civilian forced laborers. In most cases, the services provided fell far short of those available to Germans.

The public health insurance funds issued a member and benefit card (Mitglieder- und Leistungskarte) for each person who was insured with them. The different public health insurance funds used different preprinted cards, which vary in terms of color and layout. Although they look different at first glance, they always contain the same information in virtually every case.

Questions and answers

-

Where was the document used and who created it?

Public health insurance fund staff created a member and benefit card for every member, i.e. both for German insured persons and for civilian forced laborers. In addition to personal details, they noted on these cards any sick days, diagnoses, and medical treatments that were reported to them by doctors and hospitals. The public health insurance funds filed these cards in their records.

- When was the document used?

Member and benefit cards are typical documents issued by German public health insurance funds. They existed for all insured persons even before the Nazis came to power, and they continued to be used after the end of the war.

- What was the document used for?

Member and benefit cards allowed public health insurance fund staff to keep track of the people insured with them and of the medical treatment they received. They entered the personal details of the insured person on the card for administration purposes: In addition to name and address, there were details of the employer and the start of the insurance (date of joining). If the person fell ill, they entered details of their illness and for how long they were unfit for work, and also what treatments (benefits) the public health insurance fund had paid for. The public health insurance funds recorded all the information they had about a person on these cards. They used the information to compile statistics among other things.

After the end of the Second World War, public health insurance fund documents were important for clarifying the fates of the people they related to. As part of the foreigner tracing campaign (Ausländersuchaktion), companies, authorities, insurance companies, and other agencies were required on orders from the Allies to hand over original documents such as member and benefit cards. These documents were able to provide information about civilian forced laborers who had been in in the German Reich since 1939, or had been deported there.

- How common is the document?

The public health insurance funds issued a member and benefit card for all those who were insured with them. So there must have been millions of these sorts of cards for civilian forced laborers. However, by no means all of them have survived.

The member and benefit cards that came to the International Tracing Service (ITS), the predecessor institution of the Arolsen Archives, are therefore exceptions rather than the rule. As the ITS staff sorted the cards alphabetically into the War Time Card File (Collection 2.2.2.1), which contains 4.2 million documents, and in doing so dissolved coherent card indexes, it is unfortunately not known how many member and benefit cards have been preserved in the Arolsen Archives. Consequently, it is often not possible to say which public health insurance fund the cards originate from. But in the near future, modern computer technology will at least find the answer to the question of how many there are: clustering techniques will make it possible to identify member and benefit cards, as well as other documents, and to virtually collate cards of the same type.

- What should be considered when working with the document?

It all sounded fair on paper: All civilian forced laborers were covered by health insurance, even Polish and Soviet civilian laborers who were initially excluded. If they became ill, they had insurance coverage in theory, and the cost of visits to the doctor, medical treatment, and medication would be met by this health insurance. In the case of certain groups, mainly people from countries allied to the German Reich, even family members in the native countries were also covered by the insurance, this was the case for Italian, Hungarian, Romanian, Belgian, or Danish civilian laborers, for example. The civilian forced laborers were required to pay part of their wages into the health insurance scheme. However, the actual medical treatment civilian forced laborers received depended heavily on their nationality. Western European civilian laborers received similar medical treatment to German patients in accordance with Nazi ideology. Civilian forced laborers from central and eastern Europe received only basic treatment, if indeed they received any treatment at all. Soviet civilian laborers were excluded from adequate medical treatment altogether.

Civilian forced laborers, in particular Polish and Soviet forced laborers, were generally exposed to a high risk of illness. Due to the lack of hygiene during the long journey to the German Reich, many arrived at transit camps and communal accommodation already infested with lice and suffering from other illnesses. Diseases could spread quickly in the often poorly equipped and frequently overcrowded barracks in the camps. Civilian forced laborers were also exposed to many dangers at their place of work. The fact that they had to handle hazardous materials without adequate protective clothing as well as the weakness and lack of concentration that resulted from inadequate nutrition led to many accidents.

Generally speaking, medical treatment was often aimed at the short-term restoration of a person’s ability to work. Sick or pregnant civilian laborers were sent back to their native countries in the early years if they were unable to work for more than two or three weeks (eight weeks from February 1944 onwards). However, medical care in the German Reich was also often inadequate. There is evidence, for example, that the public health insurance funds refused to pay for hospital treatment or for certain medicines. Instead, sick civilian laborers were often simply accommodated in infirmaries attached to the communal barracks provided by companies, or in separate areas of public hospitals, when contagious diseases such as tuberculosis were spreading in their living quarters, for example. The conditions were atrocious, particularly in the camps. Whether time off work was granted for illness and whether medical treatment was provided also depended on the employers. The destruction that ensued as a result of the bombing campaigns also meant that medical care was very poor especially in the last months of the war.

If you have any additional information about this document, please send your feedback to eguide@arolsen-archives.org. New findings can always be incorporated into the e-Guide and shared with everyone.

Help for documents

About the scan of this document <br> Markings on scan <br> Questions and answers about the document <br> More sample cards <br> Variants of the document