Page of

Page/

- Reference

- Intro

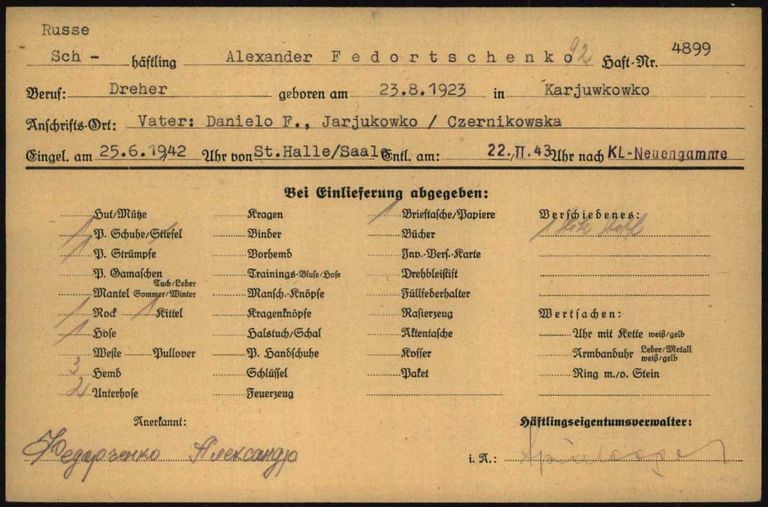

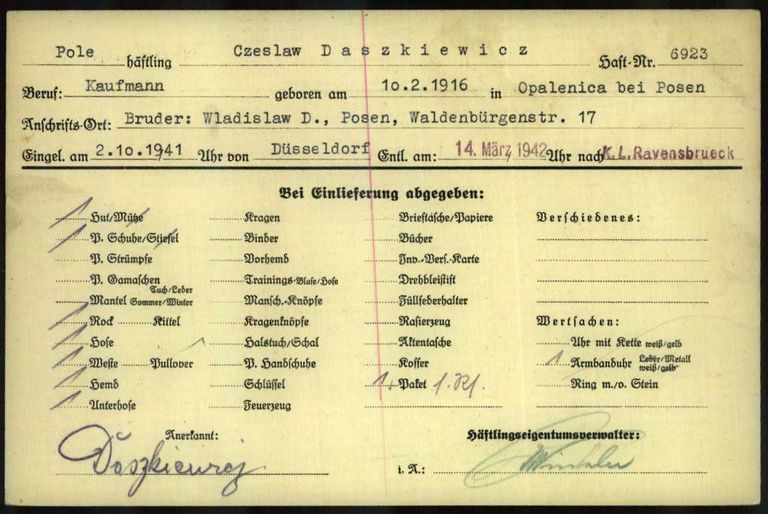

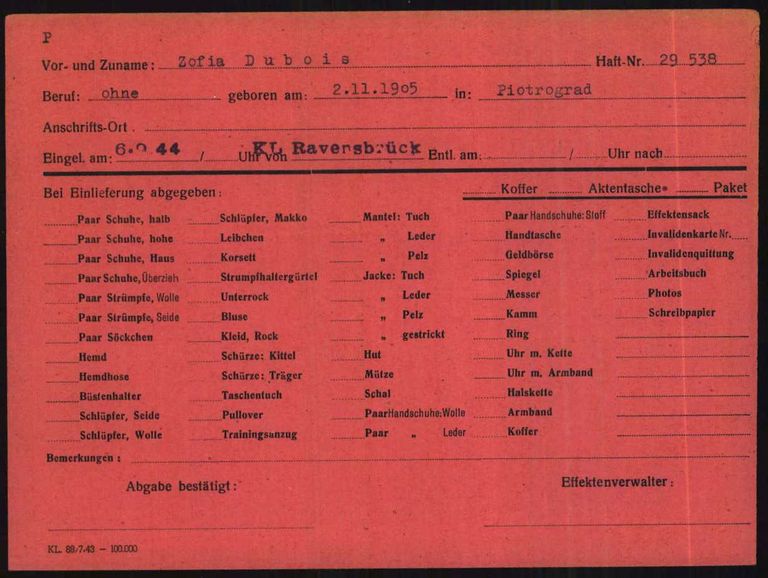

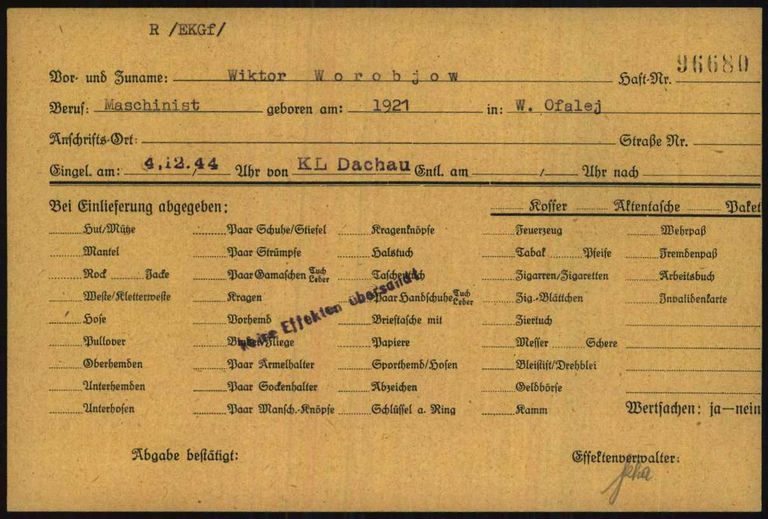

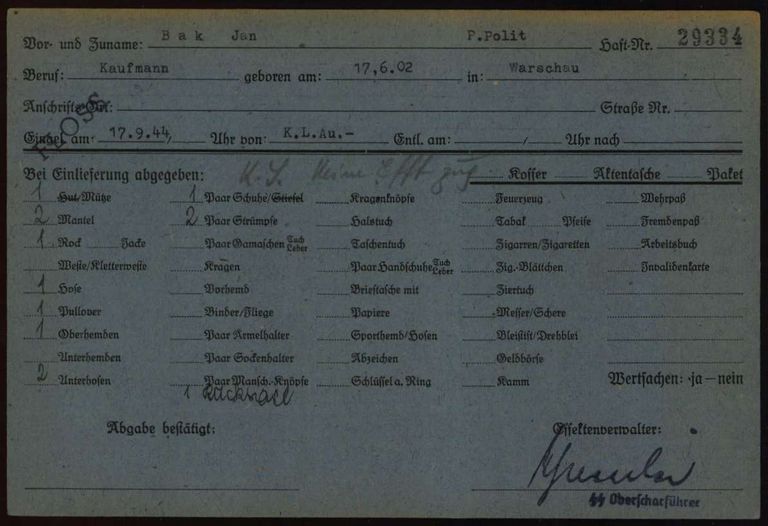

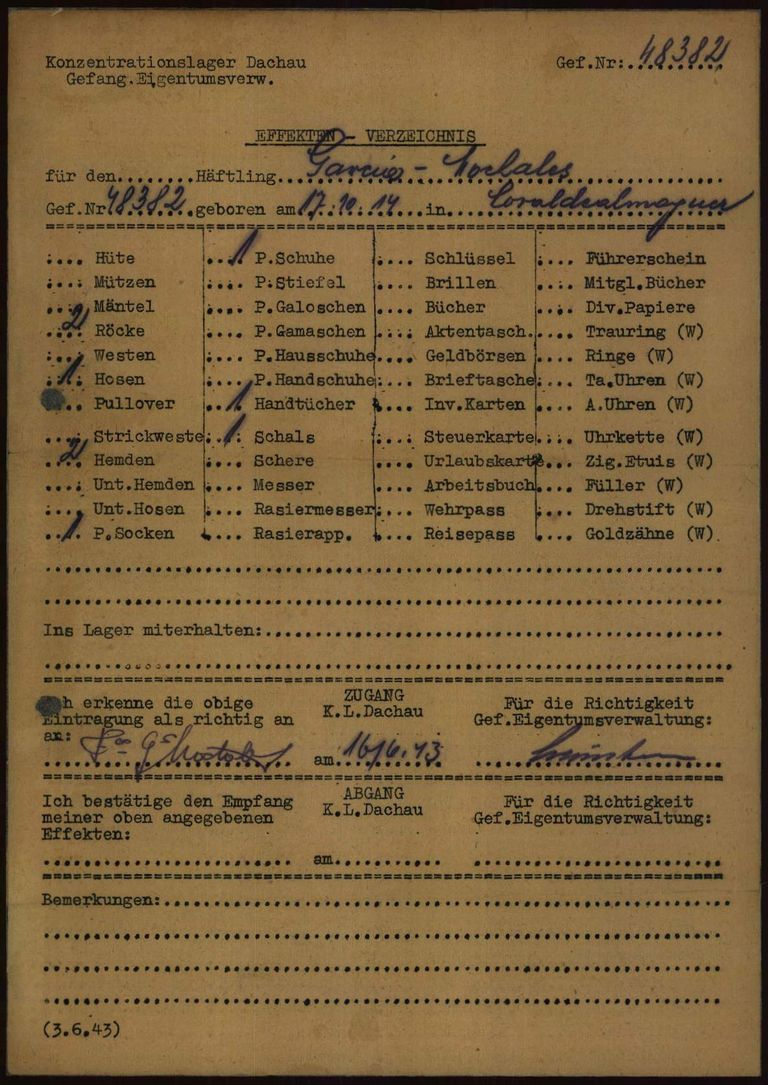

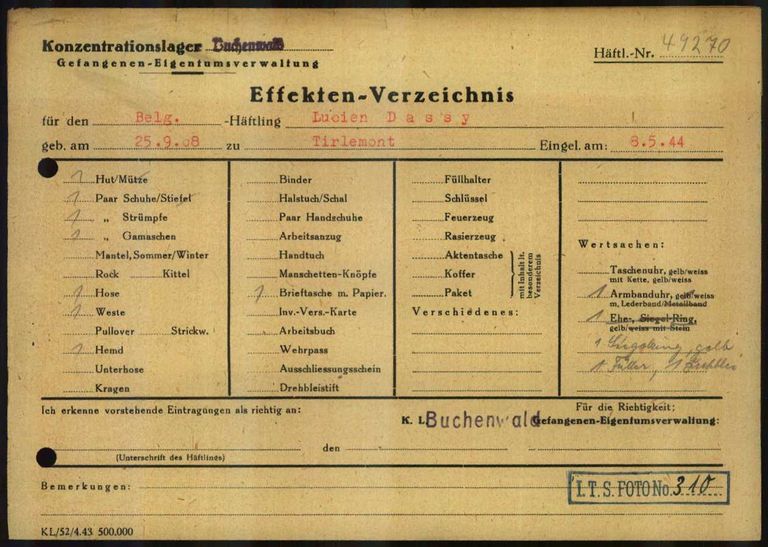

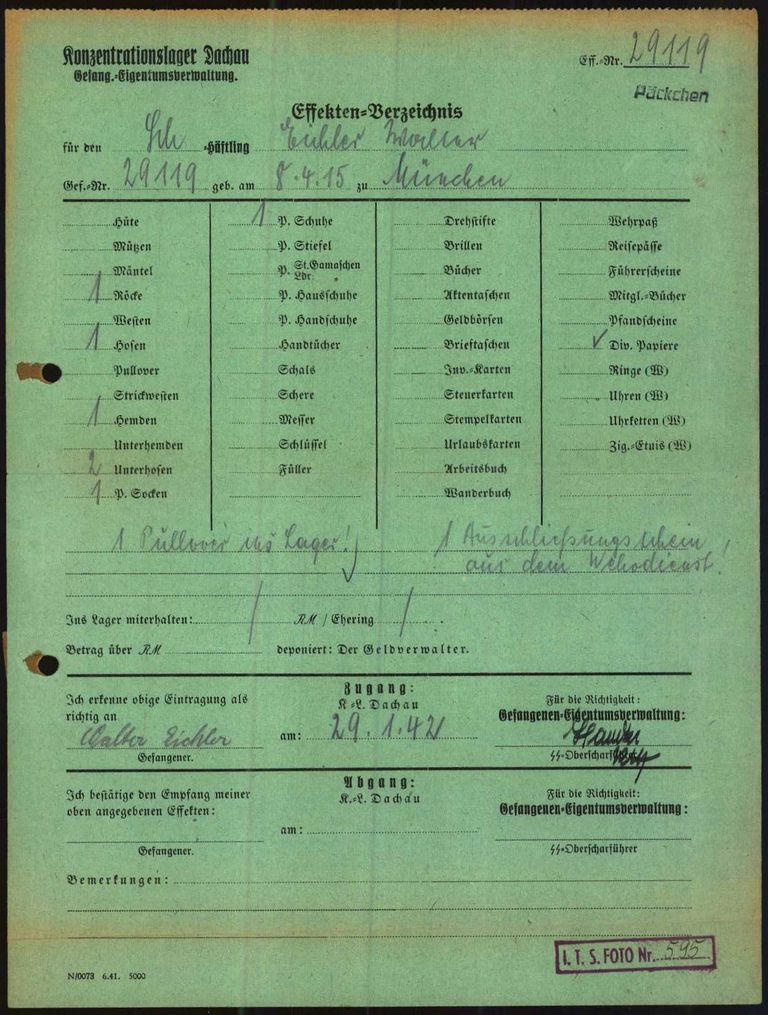

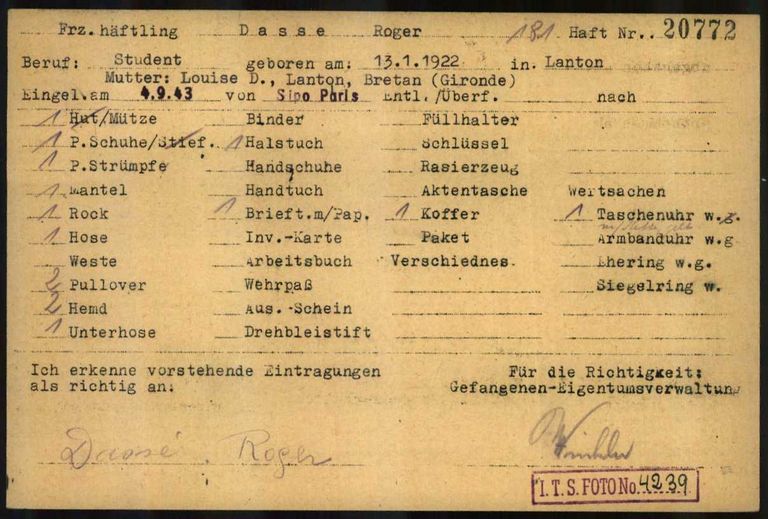

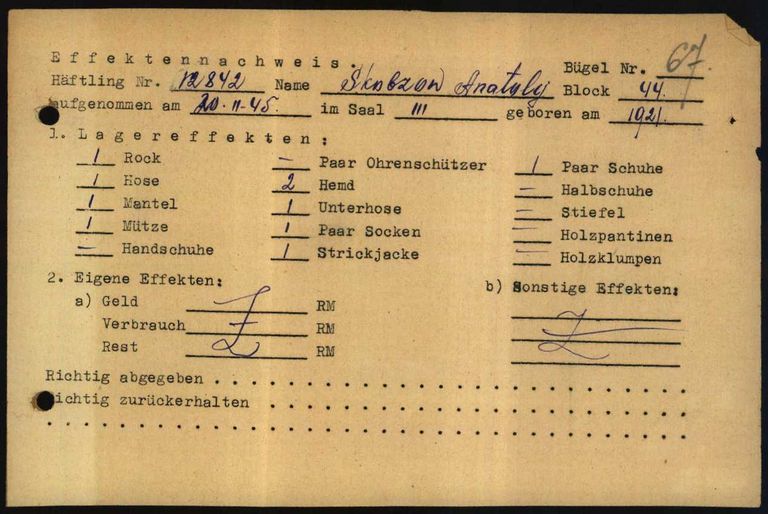

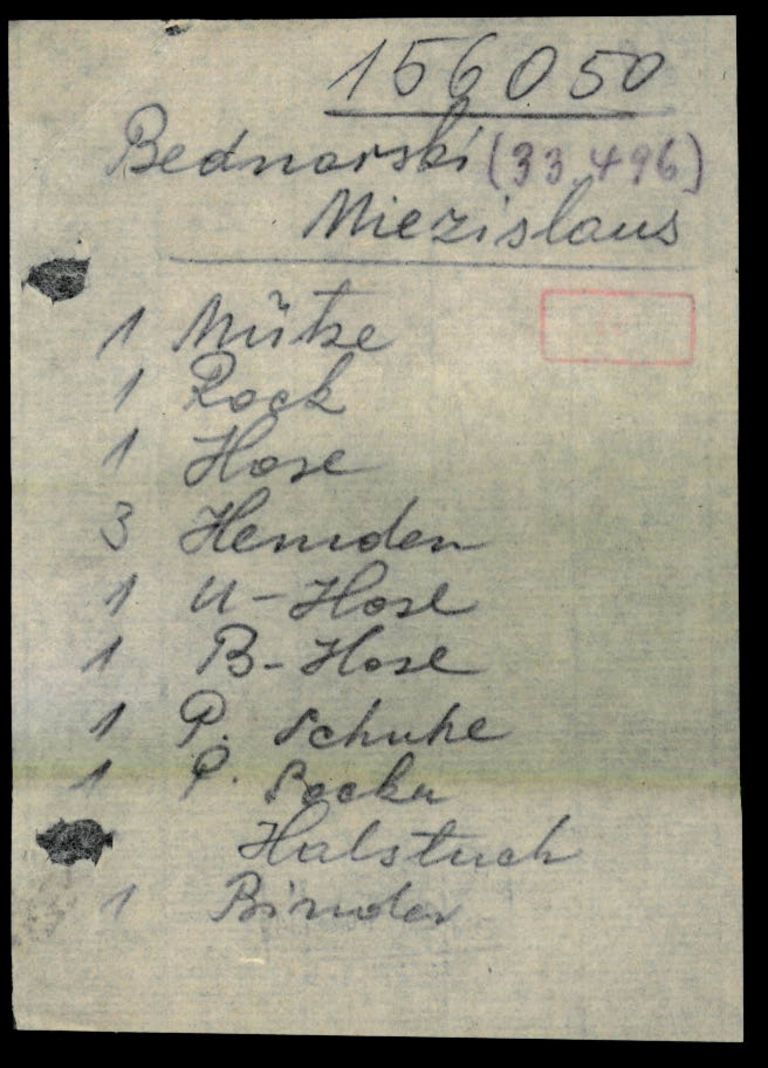

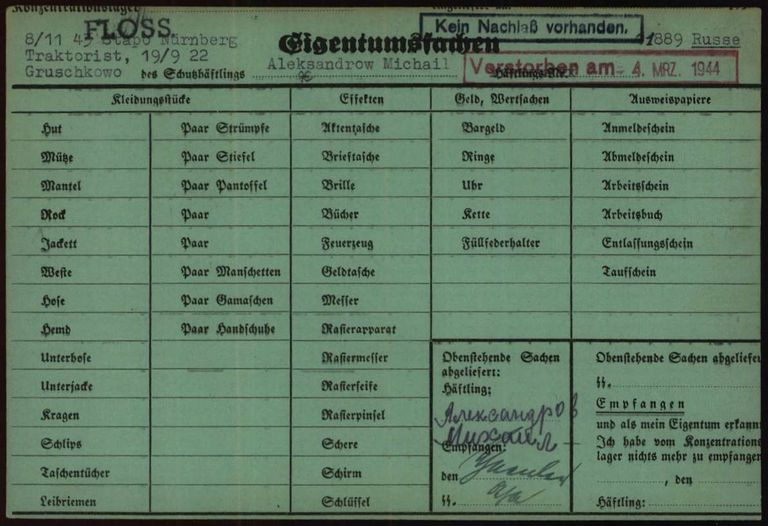

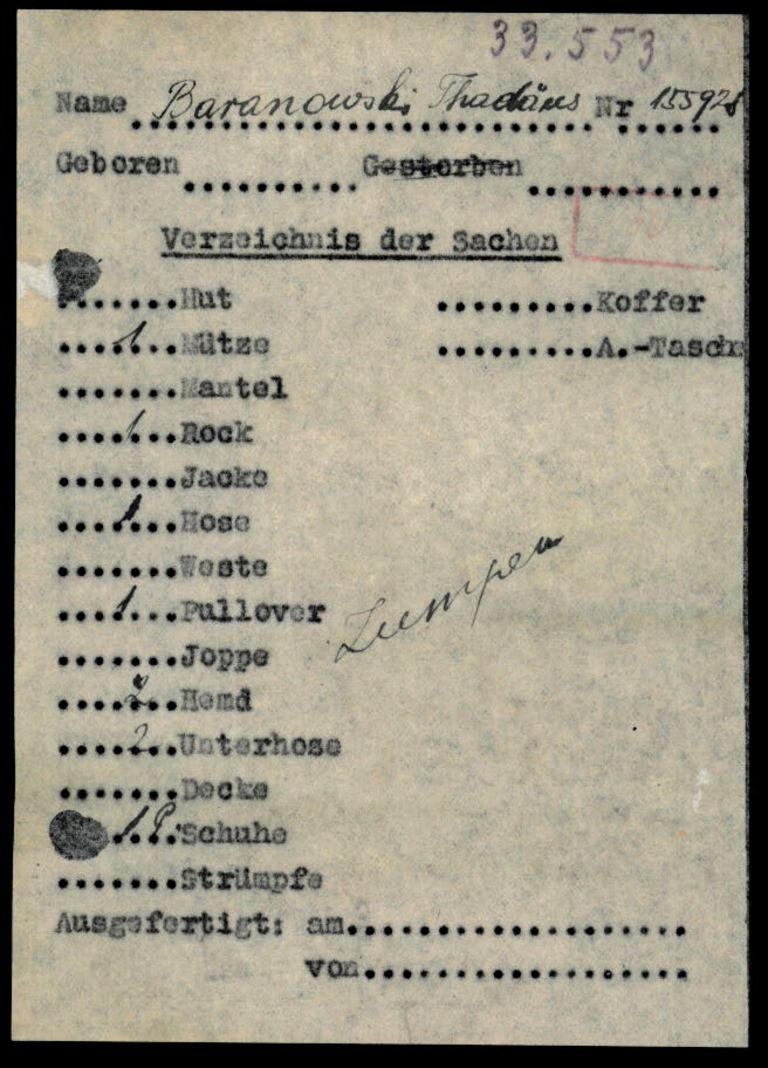

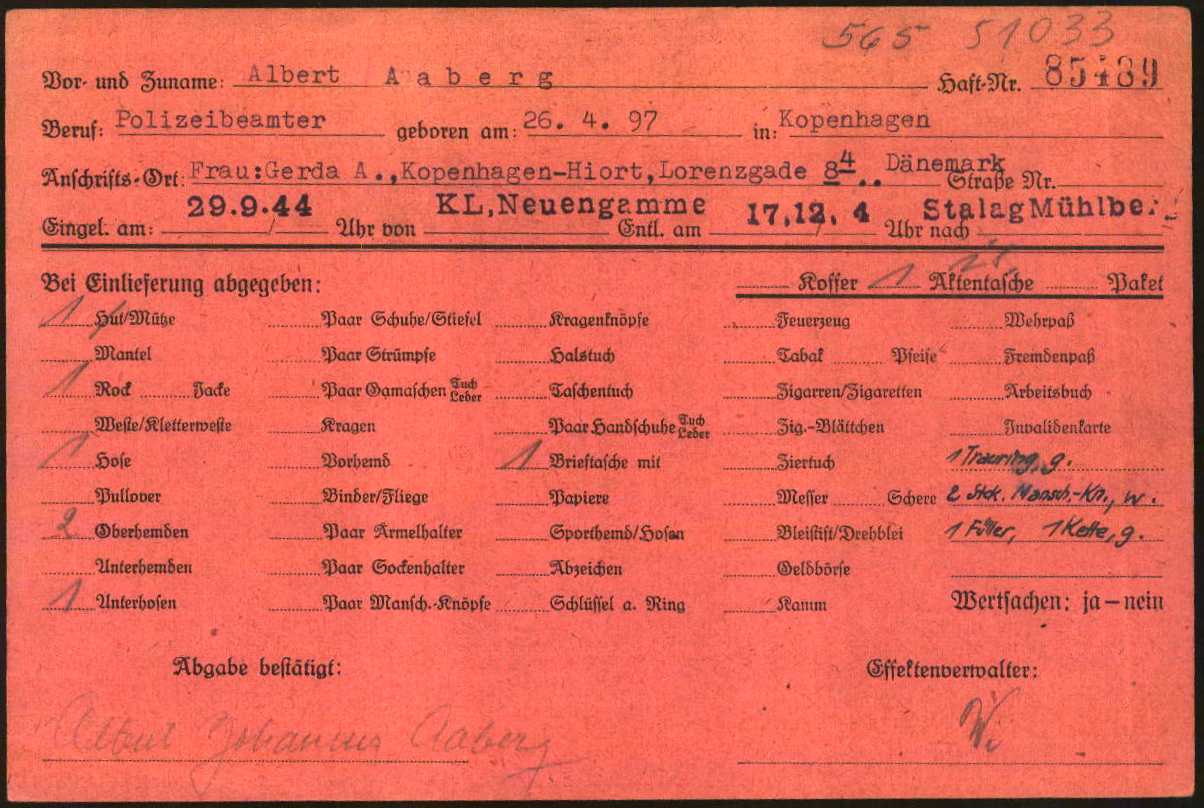

This document is a personal effects card. Although these cards come in different colors, they all served the same purpose: they were used to record the personal belongings that prisoners were forced to hand over when they arrived at a concentration camp. The personal effects cards were filled out in very different ways. Cards from before the war tend to have more items checked off or numbered than cards from 1939 onwards. Many of the cards from 1944 and 1945 are entirely blank because the prisoners no longer had any belongings when they were transferred to a camp. Different stamps on the personal effects cards indicate what happened to the items. Decrees and regulations issued during the war led to more and more personal effects being confiscated and used for other purposes.

This document is a personal effects card. Although these cards come in different colors, they all served the same purpose: they were used to record the personal belongings that prisoners were forced to hand over when they arrived at a concentration camp. The personal effects cards were filled out in very different ways. Cards from before the war tend to have more items checked off or numbered than cards from 1939 onwards. Many of the cards from 1944 and 1945 are entirely blank because the prisoners no longer had any belongings when they were transferred to a camp. Different stamps on the personal effects cards indicate what happened to the items. Decrees and regulations issued during the war led to more and more personal effects being confiscated and used for other purposes.

Questions and answers

-

Where was the document used and who created it?

When prisoners arrived at a concentration camp, in addition to being registered, shaved and given their camp clothing, they were also taken to the personal effects storage room, where they had to hand over everything they had brought with them. The term “room” is misleading, because it was not a small space. In Buchenwald, for example, the personal effects storage room, which held all of the prisoners’ possessions, was the biggest building in the camp.

Newcomers had to hand over all of their valuables and clothing, known as their “effects” (an old term for personal property). Prisoner functionaries would fill out a personal effects card for each prisoner, recording what the prisoners had with them. These cards were filed in alphabetical order in the personal effects storage room. If a prisoner was transferred to another camp, a new personal effects card would be filled out in the new camp.

- When was the document used?

Personal effects cards are documents that were used in all German prisons even before 1933. The Nazis continued this practice and used such cards in the early concentration camps to manage the items that prisoners had to hand over when they arrived. Different versions of these personal effects cards were used in the main camps throughout the period from 1933 to 1945. The color of the cards can vary, but this was mainly due to the growing shortage of paper during the war. Most of the cards in the Arolsen Archives are reddish, though some are yellow or brownish; very rarely they can be blue as well. The items pre-printed on the cards – such as hat, shoes, stockings, collar and pencil – can also vary on the different versions of the personal effects cards.

- What was the document used for?

Personal effects cards were used to record the possessions that newly arrived prisoners had to hand over to the personal effects storage room. Personal effects were usually stored for the prisoners in the concentration camps, as they would be in a prison, so that they could be returned when the prisoner was released. Before the start of World War II, a prisoner’s valuables – such as watches, fountain pens, identification papers, photographs or clothing – would normally be returned upon the prisoner’s release. If a prisoner died in the concentration camp, the camp administration would send the personal effects to his or her relatives.

If prisoners were transferred – especially before the war, but even during it – their personal effects could be sent on from one camp to the other. The Arolsen Archives have many letters from camp administrators asking about the personal effects of transferred prisoners that were supposed to be sent on to them. In some cases, the SS would put the personal effects in sacks and send them along with their owners when the prisoners were transferred to another camp. In other cases, however, the possessions were sent at a later date. Personal effects could also officially be aufgelöst or “dispersed,” as the Nazis put it. This meant that the clothing of deceased or transferred prisoners would not be sent on, but would instead be disinfected and washed before being distributed to new arrivals.

In the last years of the war, the SS took very different approaches to handling prisoner possessions. Most of these possessions were verwertet (“recovered”), meaning that valuables were confiscated and sold. The prisoners would then not have their personal effects returned to them if they were transferred or released. This economic exploitation was official Nazi policy, and in many cases even the prisoners’ clothing was given to the German People’s Welfare Organization or the Winter Relief Organization, or – as mentioned – distributed to newcomers to be used as their camp clothing. Some of the valuables would wind up on the black market or would be exchanged for food. Many survivors also report that female concentration camp guards and SS men, as well as corrupt kapos and prisoner functionaries, would take valuables for themselves.

The way in which personal effects were handled changed during the course of the war, and it also depended on the nationality of the prisoner. If a German or Western European prisoner died, it was necessary to report this to the admitting authority, which, in turn, was supposed to find local relatives to whom the concentration camp administration could send their valuables. By 1942 at the latest, however, Polish, Jewish and Soviet prisoners were excepted from this regulation; the SS usually confiscated their personal effects for the enrichment of the German Reich. A decree from the SS Chief Economic and Administration Office from November 11, 1944, finally ordered that the personal effects of foreign prisoners should fundamentally no longer be returned. Their personal effects cards were stamped accordingly.

Personal effects belonging to about 3000 prisoners, most of whom were detained in the Neuengamme and Dachau concentration camps, have been preserved in the Arolsen Archives. The remarkable thing is that the names of the owners of many of these personal effects are known. This is what prompted the launch of the #StolenMemory campaign in 2016 to help search for the families of the people concerned. The watches, photographs, wedding rings, and other personal items are returned to them.

- How common is the document?

Personal effects cards were relatively common documents that were filled out for most prisoners in the concentration camps. They were even filled out for prisoners who had nothing with them when they arrived at a camp. In these cases, the card would be blank except for the prisoner’s personal details, or it would be stamped with keine Effekten übersandt (“no effects sent”). It is not possible to say exactly how many personal effects cards are stored in the Arolsen Archives. But a list from 1951 mentions – as a rough framework – 110,000 personal effects cards from Buchenwald and nearly 700 from the Niederhagen-Wewelsburg concentration camp.

- What should be considered when working with the document?

The personal effects cards can be used to determine how long someone had been imprisoned. When a prisoner was admitted to a concentration camp for the first time, their card might list a variety of everyday objects that they had with them when they were arrested. Prisoners who had already passed through multiple camps, however, often had no more possessions to record. This is why the section labeled Bei Einlieferung abgegeben (“submitted upon arrival”) can be completely blank on many cards, especially in the later years of the war.

It is also important to remember that no personal effects cards were filled out for the many people who were murdered in extermination camps without being registered. Their possessions were stolen as soon as they arrived at the camp.

If you have any additional information about this document or any other documents described in the e-Guide, we would appreciate it very much if you could send your feedback to eguide@arolsen-archives.org. The document descriptions are updated regularly – and the best way for us to do this is by incorporating the knowledge you share with us.

Help for documents

About the scan of this document <br> Markings on scan <br> Questions and answers about the document <br> More sample cards <br> Variants of the document