Page of

Page/

- Reference

- Intro

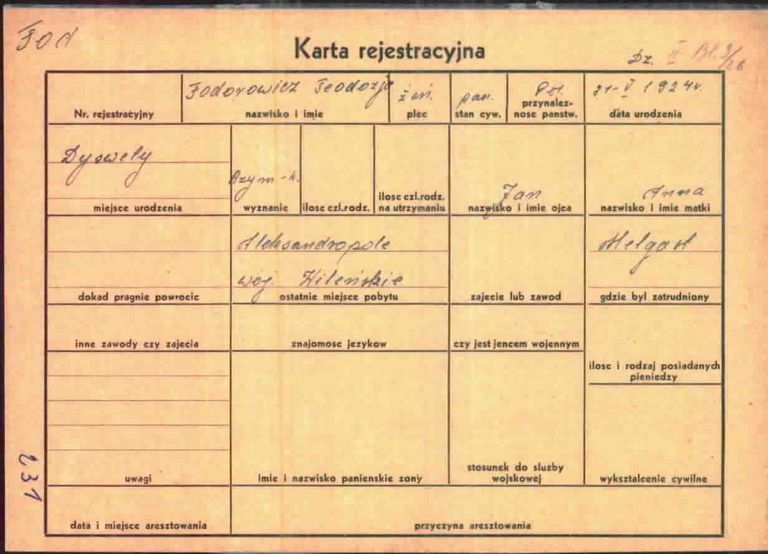

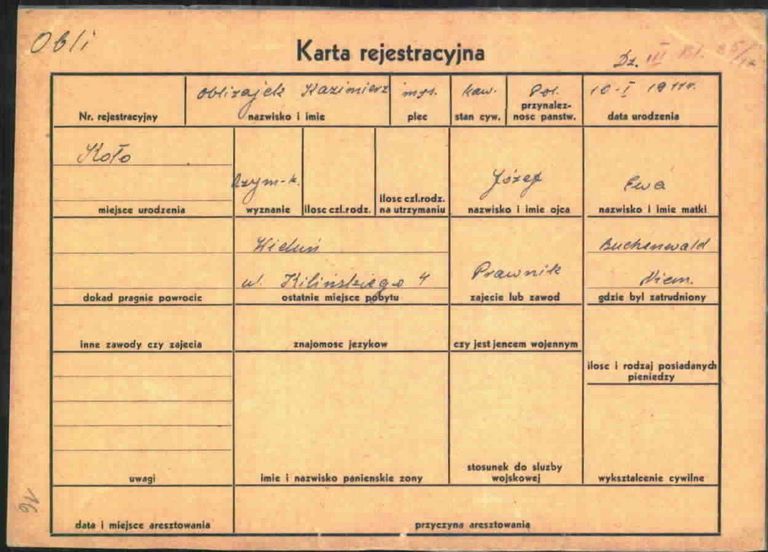

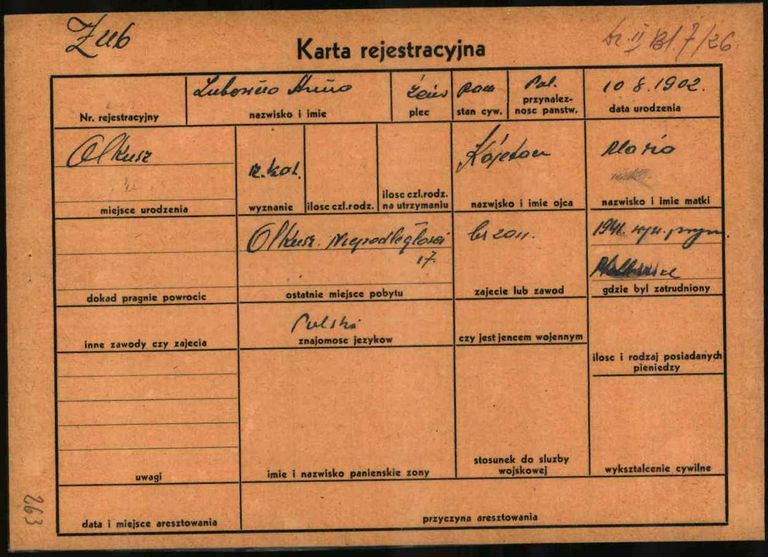

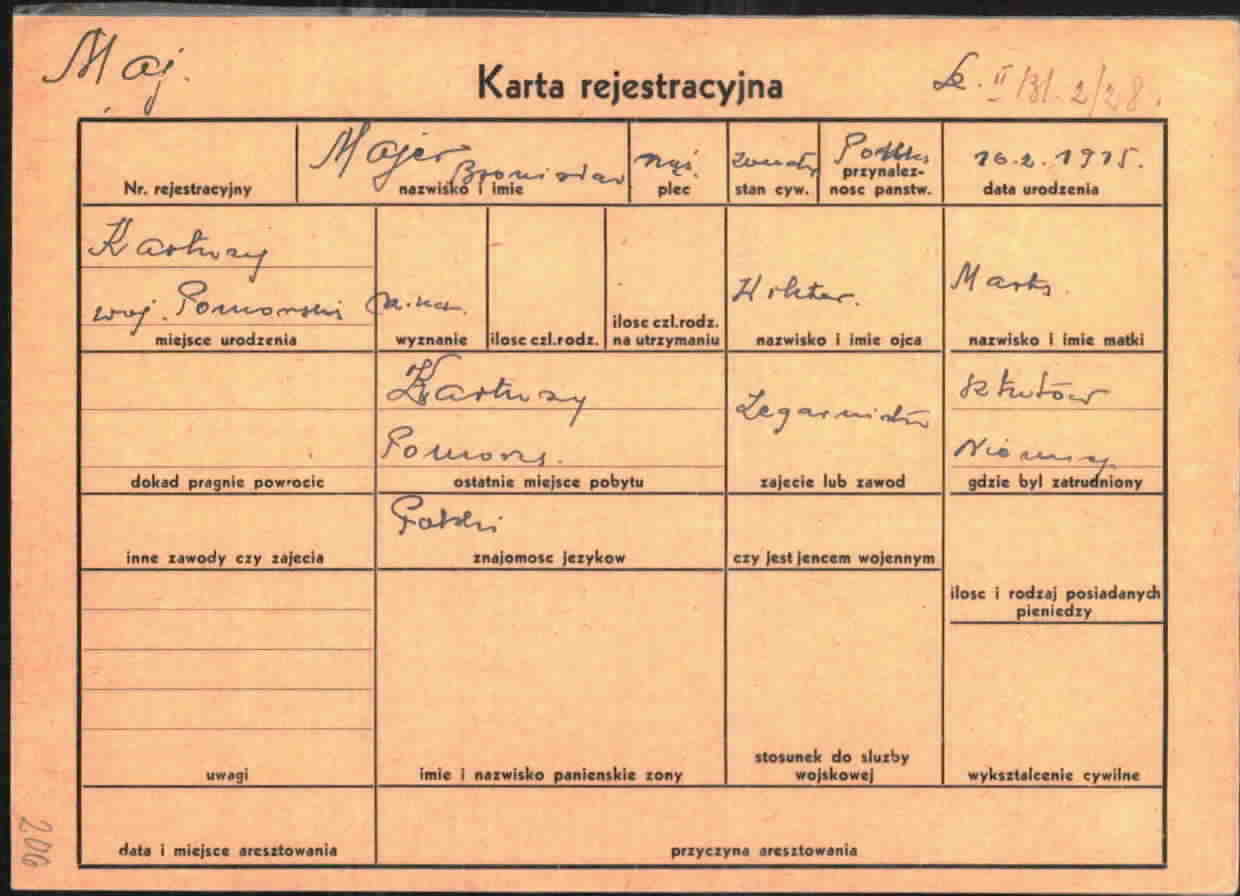

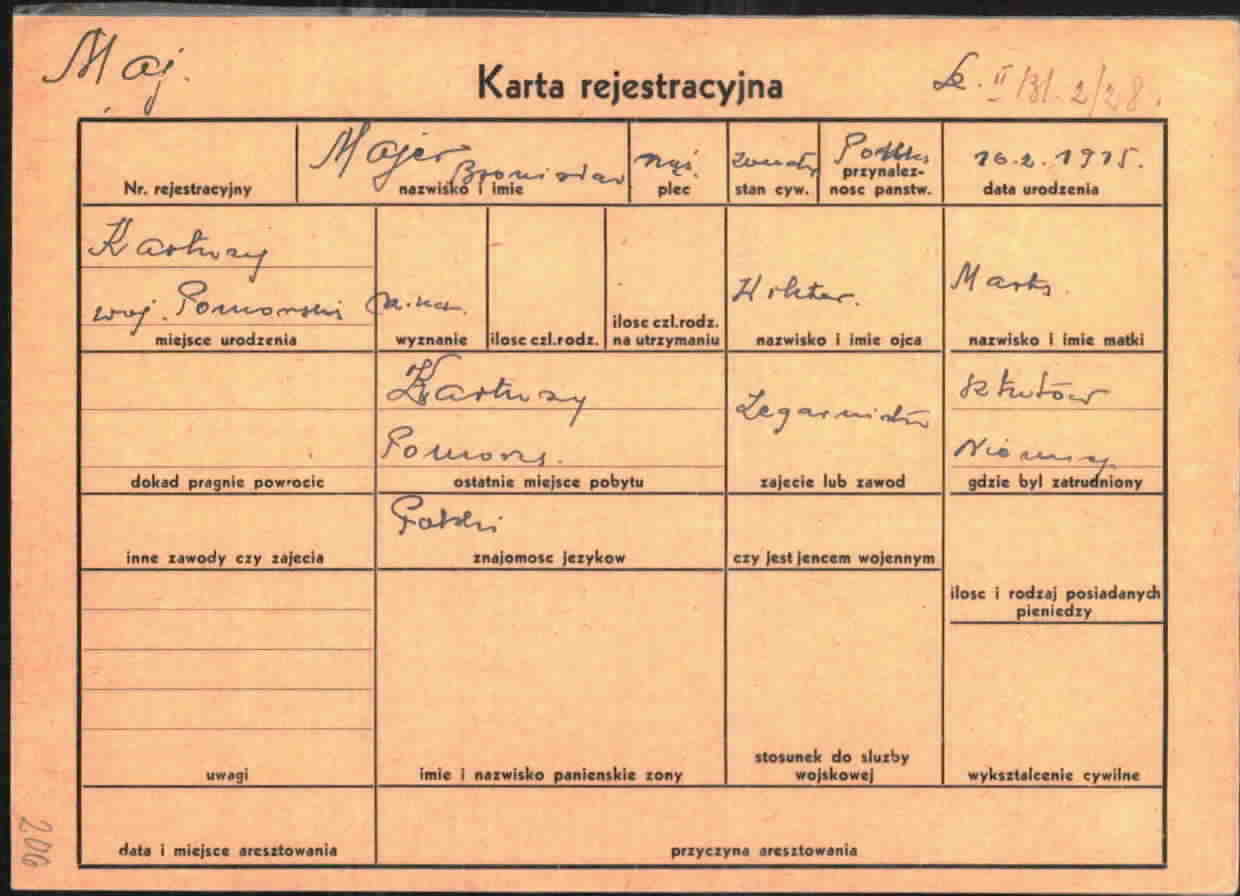

After the war, tens of thousands of DPs were housed in the Fallingbostel DP camp in what is now the state of Lower Saxony. The Polish DPs in this camp were registered in their own card file. The Polish-language registration cards (karta rejestracyjna) were used for personal details such as the DPs’ birthdate, number of family members and language skills. They also noted where the DP was housed in the camp. If this registration card exists for a DP, it means that the person spent at least a short time in Camp Fallingbostel.

After the war, tens of thousands of DPs were housed in the Fallingbostel DP camp in what is now the state of Lower Saxony. The Polish DPs in this camp were registered in their own card file. The Polish-language registration cards (karta rejestracyjna) were used for personal details such as the DPs’ birthdate, number of family members and language skills. They also noted where the DP was housed in the camp. If this registration card exists for a DP, it means that the person spent at least a short time in Camp Fallingbostel.

Questions and answers

-

Where was the document used and who created it?

After the end of World War II, there were many Polish DPs living in the Western occupation zones. Of the total of around 1.2 million DPs who were still in Germany in the autumn/winter of 1945, more than 900,000 were Polish. When the Allies decided to house the DPs together by nationality, many camps were established that exclusively or mostly held Polish DPs. For example, there were 20,000 Polish DPs in the Wildflecken DP camp and around 10,000 in the Polish camp in Bergen-Belsen.

In the British zone, between Hamburg and Hanover, there was another camp for Polish DPs: Camp Fallingbostel. The DPs there were registered following the regular UNRRA process with a DP 2 and DP 3 card, but their details were also recorded on Polish-language registration cards (karta rejestracyjna). It is not clear exactly who created these cards or the associated personal cards (karta ewidencyjna). Polish aid organizations are one possibility, as are Polish liaison officers. These officers were the links between the DPs in the camps, the British military authorities, UNRRA and the governments back home. Since they dealt with many DP concerns, they might have kept their own card file. However, it is more likely that the card file was created for the self-administration of the camp. The small UNRRA leadership team had to rely on the Polish DPs themselves to handle many everyday tasks in the camp. This supposition is backed up by the fact that the cards have handwritten notes specifying where the DPs were housed in the camp. This information would have been very important for local administrative purposes.

Since there are no further clues on the cards, researchers have not been able to determine exactly who used the cards. They definitely came from Camp Fallingbostel, however. This means that a DP who has a card like this was in the camp for at least a short time.

- When was the document used?

One of the earliest Polish registration cards preserved in the Arolsen Archives was created in July 1945. This date is not noted on the card itself, however, but rather on the associated personal card (karta ewidencyjna). Since the two cards were created at the same time, the date on the personal card also applies to the registration card.

Camp Fallingbostel existed until at least 1950, and possibly even until the mid-1950s. It is not known whether the cards were still being created at this time. What is certain is that the registration cards were sent to the ITS before 1968, as that is the year in which ITS employees placed them in the postwar card file (Nachkriegszeitkartei, Collection 3.1.1.1).

- What was the document used for?

Polish DPs were in a special situation in Germany after the end of the war. At the Yalta Conference, the Allies had agreed that Soviet DPs were to be returned first to their countries of origin. Liberated Polish forced laborers and concentration camp prisoners therefore initially remained behind in DP camps in the Western occupation zones, because the transport vehicles and routes to the east were filled. Researchers estimate that in the spring of 1946, up to 70 percent of all DPs in the Western occupation zones were Polish; in the British zone alone there were 230,000 Poles in need of care. This led to the creation of large Polish DP camps like the one in Fallingbostel. Over 22,600 Polish DPs were registered there in March 1946.

The number of Polish DPs remained high. Though some returned to their places of origin in the autumn of 1945, a “hard core” formed consisting of those who did not want to go back. There were various reasons for this. Some Polish DPs feared that they would be viewed as collaborators in Poland. Others cited political reasons for not wanting to live in a communist Poland that was tied to the Soviet Union. Additionally, more and more letters, newspapers and rumors reached the Polish DPs describing the shortage of food in war-ravaged Poland. The non-communist Polish Government-in-Exile in London also argued against returning, both through leaflets circulated in the camps and through its liaison officers.

The decision was especially difficult for Polish DPs whose nationality could not be precisely determined. The war had shifted the borders in Central and Eastern Europe. After 1918, Poland had still encompassed a large territory in the East that reached almost to Minsk, including parts of what is today western Ukraine around Lviv and Ternopil. These regions fell under Soviet rule in 1945 when Poland’s eastern border was pushed west. The previously Polish city of Lwów, for example, became the Ukrainian Lviv. This meant that DPs who had been born in the same place could define themselves as either Polish, Soviet, Ukrainian or stateless.

The number of Polish DPs in the camps in the British zone declined slowly. The British military government and UNRRA repeatedly argued that they were only providing care in Germany on a temporary basis. They threatened to revoke the DP status of Poles who continued to refuse to return home. There were even campaigns with lectures, posters, flyers and films meant to convince the DPs to voluntarily report for transports back to Poland. This was because even though many Polish DPs were hoping to emigrate, the strict entry quotas that were in place in most countries meant emigration was not a realistic option for them for a long time. A change only came with the “Polish Repatriation Drive” of the Allied military government and the Polish government. All DPs who reported for repatriation by the end of 1946 received 60 days worth of food rations after they returned to Poland. Over 9,000 Polish DPs took up this offer.

On account of this special situation after the war, tens of thousands of Polish DPs found themselves in the DP camp in Fallingbostel. Unfortunately, it is not possible to say exactly who created the registration and personal cards for them and what they were used for in the Fallingbostel camp. This is partially because the history of the Fallingbostel DP camp has not been very well researched, even though a large number of people lived there for many years. If you have any further information about this camp, please send your feedback to eguide@arolsen-archives.org.

- How common is the document?

It is difficult to say how many registration cards from the Fallingbostel DP camp have been preserved in the Arolsen Archives. ITS employees separated the card file, organized the cards following an alphabetical-phonetic system and placed them in the postwar card file (Nachkriegszeitkartei, Collection 3.1.1.1), which now holds several million documents. This made it easier to search for references to people, but it also means that it is no longer possible to determine how common the registration cards are. However, in the near future, modern computer technology will find the answer: clustering techniques will make it possible to virtually reassemble the card index from Fallingbostel – as well as other card files. In any case, cards have definitely not been preserved for all of the Polish DPs from Fallingbostel.

- What should be considered when working with the document?

On all of the registration cards examined thus far, many of the fields are blank. The fields in the bottom half of the card in particular are almost never filled out. Since the questions about imprisonment (aresztowanie) were not answered, it is not possible to trace the path of persecution experienced by the DPs before they arrived in Fallingbostel.

In general, these registration cards provide very little help when researching the course of a DPs life. An individual’s arrival date in Fallingbostel can be determined by looking at the associated personal card if it has been preserved in the Arolsen Archives. But the registration cards give no indication of how long the DPs stayed in Fallingbostel, where they went from there or whether they actually emigrated. The cards only prove that the DP was in Camp Fallingbostel at some point.

In the postwar card file of the Arolsen Archives there are also other Polish-language cards that were not produced in the Fallingbostel DP camp. For example, there are yellow and blue cards which first give the number of the DP’s food ration card (karta żywnościowa). According to the stamp on some of these cards, they came from the Polish Civil Camp in Kassel-Möncheberg. Another card comes from the Polish Red Cross in Munich. The employees there filled out a karta rejestracyjna zmarłych (registration card for deceased individuals) for Poles who had not survived the war and persecution. These cards noted the person’s name, date of death and place of burial, as well as the address of their next of kin.

If you have any additional information about the registration cards from the Fallingbostel DP camp, we would appreciate it very much if you could send your feedback to eguide@arolsen-archives.org. New findings can always be incorporated into the e-Guide and shared with everyone.

Help for documents

About the scan of this document <br> Markings on scan <br> Questions and answers about the document <br> More sample cards <br> Variants of the document